John O’Connor’s exhibition at Farm Projects in Wellfleet takes its title from a phrase his grandfather used to say: “Wind up the cat and put the clock out.” It had something to do with bedtime. It wasn’t his only original turn of phrase — O’Connor remembers his grandfather commenting on someone’s “flannel tongue,” a take on the more common expression “velvet tongue.” That was the title of O’Connor’s 2008 exhibition at New York’s Pierogi Gallery.

After spending some time with O’Connor’s art, it’s clear why these phrases stuck with him. His exuberant drawings reveal an interest in the slipperiness of meaning and his attunement to colloquial language and imagery.

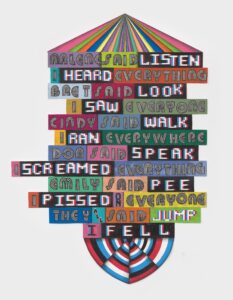

The high-key colors in The Go-Getter, a large work on view at Farm Projects, recall the world of advertising and the packaging of consumer goods. There’s also something reminiscent of a circus tent in the multi-color triangular form sitting at the top of the composition. Like many of O’Connor’s images, this one features words. “Arlene said listen,” it begins and continues, “I heard everything.” The phrases progress as if in a call and response conveying the enthusiastic if slightly loony voice of an overachiever. By the end of the top-to-bottom composition, we’re in the territory of dark comedy: “Emily said pee, I pissed on everyone,” and finally, “They all said jump, I fell.”

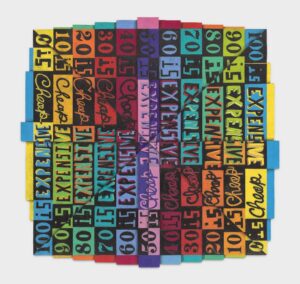

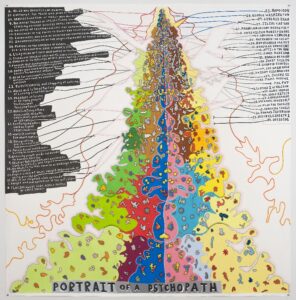

Other pictures in the exhibition have a similar transition from something innocent or folksy to something less stable and more confounding or even sinister. Psychopath, a diagram-like painting, features bubble-gum colors despite its grim title. The inversion echoes the words written next to the diagram: a list of personality traits of psychopaths and another combining leaders thought to be either successful or evil. In Indeflation, O’Connor takes on the relative value of currency. Numbers from 0 to 100 are designated as cheap or expensive, but the words and numbers move from side to side and upwards and downwards in a composition that can be hung with any orientation.

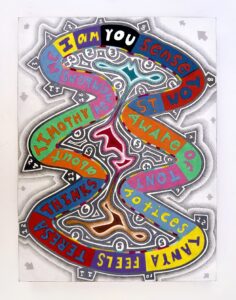

In I Am You, a recent drawing, O’Connor arranges the text in a loopy shape. The text describes perceptions of other people achieved through sensing, touching, and remembering. The loop ends, or begins, with the phrase “I am you.” O’Connor is interested in the ways that an individual can be transformed, like the way that a repeated word starts to lose its meaning, through the repeated and incremental perception of others, often through memory or media. We end up in an endless loop not knowing where we begin and where our social conditioning ends.

Although the shifting sense of reality and destabilization in O’Connor’s images introduce philosophical, theoretical, and linguistic ideas, his pictures also call to mind more down-to-earth things: board games, video games, and the lottery. O’Connor, 54, grew up in Westfield and came of age in the 1980s. The blocky forms and graphic text of his paintings feel rooted in the aesthetics of Atari or Pacman. His works are sometimes created through game-like systems, too.

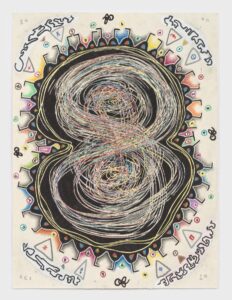

In SUSEJ, a large-scale drawing, O’Connor devised a system where he began at the center and worked outward on graph paper. While doing a residency at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture shortly after getting his M.F.A. at Pratt Institute, he began to pull from literary sources to create his systems for making images. In this piece, he worked with the first words of the Bible. In it, each colored square represents a different letter from a word, in sequence. As the image developed, he’d evaluate the results and adjust the rules according to his aesthetic judgment. The system “leads to a specificity I wouldn’t be able to make on my own,” says O’Connor. There’s something idiosyncratic in the off-kilter diamond shape radiating with multi-colored appendages.

O’Connor’s work is decidedly analog but anticipates a digital world where the relationship between personal input and algorithmic systems determines much of our reality. But his work is not utilitarian or straightforward. His systems yield something beautiful, creative, and uncanny, recalling the mathematical and mystical work of Swedish artist Hilma af Klint or monuments of ancient civilizations, where visual objects were created through a combination of systematic and mystical processes. There’s something transcendent in these images — a creative force that is linked to the artist’s will but extends beyond it.

The lottery is perhaps the one institution in contemporary American society that offers its believers the most promise for transformation. At Farm Projects, O’Connor is exhibiting three drawings on grid paper that he got from his landlord while living in Queens (O’Connor now lives in Mohegan Lake, New York). His landlord had written numbers across the paper in an attempt to predict the lottery. O’Connor used a color code to create abstract geometric images on the sheets: he alternated between warm and cool colors according to whether the number was odd or even.

The lottery and O’Connor’s art practice are parallel in many ways: there’s chance, human agency, unexpected results, the promise of something grand, but also the potential for darkness.

“The lottery was a big part of my life,” says O’Connor. “My family played birthdays and personal numbers. There was this sense that even though it was all random, it was personal, or you had some control. It was almost mystical in a way, yet no one ever won anything.”

‘Arlene Said Listen’

The event: Paintings by John O’Connor

The time: Aug. 1 through 11; opening reception Saturday, Aug. 2, 6 to 8 p.m; artist talk Friday, Aug. 8, 6 p.m.

The place: Reception and exhibition, Farm Projects, 355 Main St., Wellfleet; artist talk, Wellfleet Preservation Hall, 335 Main St.

The cost: Free