The characters in “Word Processor,” Hannah Barrett’s series of oil paintings, are secretaries, record keepers, and writers. They work in spaces filled with familiar objects: fruit, flowers, patterned rugs, telephones, teacups, and bookcases. They sit or stand at desks, typing on pre-digital machines or writing by hand. One takes its written work to the mountains, a classic black-and-white composition book in hand.

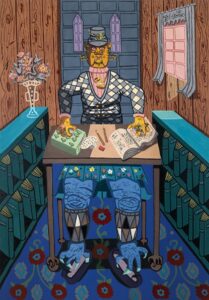

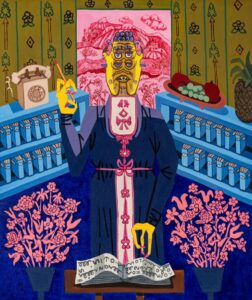

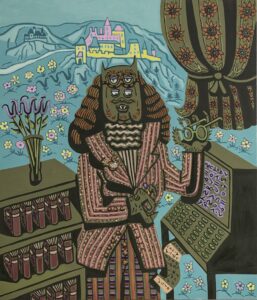

This, however, is where any feeling of familiarity ends. In the carefully imagined world of Barrett’s paintings, the main subjects are other-worldly, gender-ambiguous monsters. Some have many eyes. Others boast purple skin. All have claw-like hands and feet, and all are impeccably and colorfully dressed.

Barrett, who splits their time between the Hudson Valley and Brooklyn, grew up in Reading, Pa. in a household where reading was heavily encouraged and access to books was easy. “I thought of paintings the same way I thought about the text in stories,” they say. “I was so used to using my imagination with stories in books that when I looked at pictures, I would animate them in my mind.”

One early childhood influence for Barrett in the realm of text and image was the “Moomintroll” books by Finnish writer and visual artist Tove Jansson. Moomins are imaginary creatures with bulbous noses that exist in a world without gender. Their freedom from the gender binary was formative for Barrett.

Barrett graduated from Boston University in 1998 with an M.F.A. in painting and has explored the concept of gender ambiguity in their work for years. In 2023, they showed a series of “Monster” portraits at the Schoolhouse Gallery in Provincetown. The monsters are dandyish but also exhibit female characteristics. Some have both whiskers and breasts. Others have a masculine face but feminine hairdo. Barrett’s “Word Processor” paintings expand on this earlier work. Five of them will be on display in a group show at the Schoolhouse Gallery from Aug. 1 to 19.

For Barrett, the works are a crystallization of the relationship between narrative painting and fiction that has always felt very present for them. They think of their paintings as visual tableaux; there are no accompanying written stories, but the potential is there.

“My hope is that there is enough detail in the paintings that people who enjoy engaging the imagination in a visual way will have enough to go on,” Barrett says. “They’ll be able to look at the paintings and create their own story.”

That’s why Barrett includes so many recognizable objects in the pieces. In Progressive, the trappings of traditional still life or portraiture — books, vases of flowers, and a basket of fruit —are easy entry points into a scene that doesn’t necessarily offer easy answers.

From these starting points, viewers can begin to create their own narratives about what the four-eyed, purple-whiskered, devil-horned, long-dress-wearing monster is writing. Is it poetry? Is it law? Is it the next New York Times bestseller? Maybe it’s a history of the magenta-hued locale visible through the window.

Beyond the realm of fiction, there’s another important influence in Barrett’s work: historical portraiture, particularly 18th-century American folk portraits. The environment around the subject in these portraits is often staged to explain who the subject is: books surround the intelligent minister, a lace curtain implies a refined wife. Barrett, too, gives the subjects in paintings a set, albeit a much more open-ended and baffling one.

“I like those early folk portraits because they often have really interesting and surprising shapes,” says Barrett. “In some, there’s this jarring inconsistency in the image, where somebody’s hair just looks like the shape of a fish.” These incongruous moments result in an interruption of the image the artist is trying to present — Barrett uses this idea in their own work.

Despite the influence of historical portraiture, there’s something very pertinent to the present that comes to the fore in each “Word Processor” painting. When one looks beyond the elaborately imagined and downright odd scenes, a question of record keeping arises. Regardless of whether Barrett’s creatures are recording fact or fiction, there’s an indication of the power of the written word that is further emphasized by the filled bookshelves in each painting’s background.

In a day when fake news proliferates and a significant percentage of the media we absorb is produced by robots, the question of who gets to write history and how that history is written carries extra importance. Is trusting the record produced by a purple-skinned, three-eyed, mustachioed creature any more precarious than trusting our daily bombardment from various mega news outlets? The care and thought with which Barrett renders their imaginary scenes suggests perhaps not.

Also noteworthy is the clear absence of any digital technology in these pictures. The character in Spectacles looks like it might be using some very early computing device but certainly nothing like we are accustomed to today. Others in these portraits write by hand or use typewriter-like devices. Although the subjects of Barrett’s paintings look like aliens, their old-fashioned technology and attire, monstrosity, and gender ambiguity could all be interpreted as a kind of plea for recognition of the absurd, natural creativity of humans.

Curious Creatures

The event: Paintings by Hannah Barrett in a group show

The time: Aug. 1 to 19; opening reception Friday, Aug. 1, 6 to 9 p.m.

The place: Schoolhouse Gallery, 494 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free