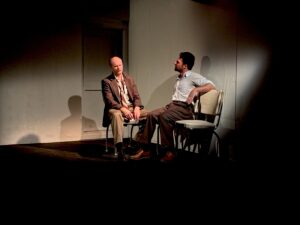

The Harbor Stage Company’s second offering of the summer is Arthur Miller’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1949 tragedy, Death of a Salesman, in a stark, audacious, and emotionally searing production directed by Robert Kropf.

Theater, unlike film, is known for revealing the seams of illusion. This production, designed by Justin Lahue, takes that idea to an extreme. The play opens on a brightly lit and nearly empty stage. We’re in the interior of the Loman household in Brooklyn, but there is no furniture except for one nondescript table. White light exposes every imperfection of the whitewashed walls. The setting provides little comfort to either the characters or the audience.

The raw, unsparing narrative of the play’s two acts exposes the delusions gripping Willy Loman, an aging American salesman. (Miller’s script famously omits any reference to what Willy actually sells.) This production opens with Willy (William Zielinski) returning home from a failed sales trip to Boston. His problems unravel in fast-paced dialogue between him and his sympathetic wife, Linda (Stacy Fischer): Willy keeps crashing the car, his debts are overwhelming his income, and his mind seems to be failing.

The couple’s two adult sons, Biff (Alex Pollock) and Happy (Jack Aschenbach), both live at home. Biff has returned to the East after a gig working with horses in Texas. We’re introduced to the brothers in a lighthearted scene where the table functions as a bunk bed. They reminisce about girls, but the atmosphere soon grows melancholic.

Pollock’s performance as Biff, a man who’s uncertain of himself, stooped, with eyes slightly downcast, cuts deep. “I’ve always made a point of not wasting my life,” he tells his brother. “And every time I come back here, I know that all I’ve done is to waste my life.”

Happy, who is more outwardly successful, is still disillusioned. He feels frustrated by working in an office. The brothers talk about buying a ranch out West, but it’s just one of many unlikely fantasies running through the play — ideas the cast members spin vividly despite the spare staging.

Most of the action takes place in the Loman home, where the drama unfolds in the dialogue between family members, but we learn a lot about the increasingly desperate state of Willy’s mind through meandering monologues, scenes where he relives the past, and conversations with his dead brother, Ben. These moments are enhanced by offstage audio, video projections, and moody lighting, notably well designed by John R. Malinowski. These effects serve as physical manifestations of memory and, in some cases, delusion. Warm, sultry lighting accompanies Willy’s memory of a past lover showering him with praise; in another scene, when he reminisces about Biff’s high school glory days, vintage video clips of football players are projected on the rear wall.

Zielinski plays Willy as affable and excitable; he shifts easily from paranoia to happiness to rage. He’s simultaneously entertaining and pathetic as a fast-talking salesman trying to sell his family a delusionally optimistic version of their past and their future. He was a star salesman, so he claims, and Biff, upon whom he places all his hopes, will become rich, successful, and well liked.

But the sepia-tinted lighting of these delusions keeps shifting back to the harsh white light of reality. Miller’s characters see occasional glimpses of the truth — none more clearly than Biff and Linda. Fischer’s powerful portrayal of Linda, fiercely protecting her husband’s dignity, is especially moving, as Biff wants to expose the truth of the family’s situation. The scenes in which he confronts his father about the crushing burden of expectation on his shoulders and despairs of any success lying over the horizon are devastating.

At the end of the play, Willy hasn’t awakened from his deluded hopes for material success, and neither has his less-cherished son, Happy, whom Aschenbach portrays as stilted and superficial. But the audience knows they’re wrong. Miller, whose family lost a small fortune in the Great Depression, was a critic of capitalism and the myth of the American Dream. This critique is in plain view in Death of a Salesman: Willy thinks his charming personality will bring him success, but the promise of wealth and the rewards of hard work grow ever more elusive.

“We’re free, we’re free,” says Linda in the last lines of the play — but are they, really? Their mortgage has finally been paid off, but the family is so ground down by the fruitless pursuit of middle-class stability that in the end there can be no celebration.

No Celebration

The event: Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman

The time: Wednesdays through Saturdays through Aug. 2 at 7 p.m.; Sunday, July 27 at 5 p.m.

The place: Harbor Stage Company, 15 Kendrick Ave., Wellfleet

The cost: $25 to $50