It is not uncommon in Provincetown to come across artists with their easels and paints set up along Commercial Street or out in the dunes. Painting en plein air — painting outside, on location, to create finished work — became popular in France in the mid-1800s when the invention of portable canvases and easels made it practical. The Barbizon School championed it as a means of capturing the light, weather, and atmosphere of a place. It soon found its way to the Cape.

Plein air painting and the development of Provincetown as an art colony went hand in hand. Charles Hawthorne founded the Cape Cod School of Art in 1899 and taught his students using models who posed on the piers here. He was a strong proponent of working directly from nature, a stance that other Provincetown-associated teachers, including Edwin Dickinson and Henry Hensche, would continue.

Mary Giammarino, Roger Braimon, and Amanda Bittner are all visiting the Outer Cape this summer for various lengths of time and plan on painting outside. Like all plein air painters, they have their unique preferences — materials, location, weather, and how social or solitary an environment is.

Studying the Light

Mary Giammarino lives in Vermont but has been coming to Provincetown since 1989 to study the Cape light. “I rent a shack and come to paint and teach,” says Giammarino. She furthers Hawthorne’s legacy by teaching plein air workshops at the Cape School of Art and other local arts centers and shows her expressionistic landscape paintings at Four Eleven Gallery.

“There’s nothing like plein air painting in Provincetown,” she says. “It’s the best. Provincetown is so diverse. I can paint street scenes with the bay. I can paint the ocean. I can paint the forest, the dunes, or the salt marshes, all within a five-minute drive.”

One of Giammarino’s favorite spots is at the end of High Head Road in North Truro, where one can view cottages and Cape Cod Bay in the distance. “It’s perfect, because I can park and work out of the back of my car,” she says. “I love to go there and study. Nobody needs another cottage painting, but the light is always changing, and the atmosphere is always different. I look one way in the evening and the village is lit up. Then I go early in the morning and look to the right and see three cottages in perfect perspective. Then there’s the way the light casts across each of them. It’s really beautiful.”

For a 180-degree view, she chooses the Race Point Visitors Center, where she can observe the stretch of land between Herring Cove and Race Point. “In the foreground, there are dunes, sand, and pitch pines,” says Giammarino. “You can see the Coast Guard station over the Province Lands, as well as the ocean. Sometimes the ocean is deep blue, and the horizon disappears. Or maybe the Coast Guard station is lit up. It’s a challenging spot. The motifs aren’t jumping out at you the way the cottages do. I love to paint from the parking lot looking out through the trees when the sun is setting and casting shadows.”

Movement and Change

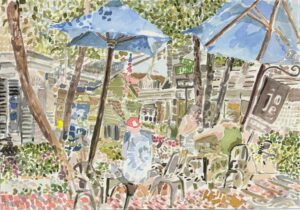

Roger Braimon lives in Westbeth, a building in Manhattan’s West Village that has provided affordable living and work space for artists since 1970, but in the summer, he often visits friends in Provincetown and paints here. Recently, he showed some of his dappled watercolors at the Provincetown Commons.

Braimon doesn’t consider himself a “typical plein air painter” who revisits the same spot regularly to observe shifts in light and weather. He often starts with more practical concerns.

“I usually pick a spot that has shade,” says Braimon. He also looks for a place where he can arrange his watercolors and that doesn’t provide too much distraction from people. “I’m not a performer who can entertain tourists while I do my work,” he says.

Braimon often finds spots along Commercial Street that fit his requirements. He finds a wealth of compositional elements at the east end of Commercial Street. “I love the predominance of grasses in all different heights and directions, and the inclusion of water, land, and landmarks,” he says. Over the course of the week it took him to paint Charles’ Place, the shoreline kept changing depending on the time of day.

Further west on Commercial Street, he made a series of watercolors responding to the energy at Joe Coffee. “This was a place with a lot of movement and change,” says Braimon. While working there, he made three one-day sketches. “It forced me to make quick decisions about what I see and what works compositionally,” he says. “Doing watercolors quickly gives a different energy.”

The Rhythms of Nature

Amanda Bittner, who has lived in Beverly for the past five years, was selected for the 2025 Ella Jackson Chair at Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill and will be teaching a workshop there this month titled Painting the Abstract Landscape. She paints and draws outside, including on camping trips around New England. Sometimes she finishes paintings and drawings outside; at other times she’ll develop ideas from her sketchbooks in studio paintings during the winter.

Bittner hasn’t painted on the Outer Cape before, but she comes with her lessons gleaned from her favorite North Shore painting spots.

Ravenswood in Gloucester is an area of wooded trails where Bittner has been painting for three or four years. She has made 30 paintings of the same beech grove.

“I was painting the tree roots,” she says. “They are such a complex subject that it would take me six to eight hours to complete a painting. It was important that I mentally and physically prepare for the day of being outside and withstanding the elements.

“I really liked the solitude that the spot provided,” says Bittner. “The quietude of the forest helped me tune in to the rhythms of nature. I don’t go back there too much now, because the more I went there, the more I would see ghostly prints of my feet on the ground. It is an indexical mark of a human in nature.”

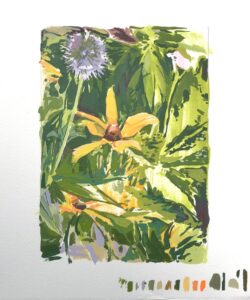

At Long Hill in Beverly, Bittner finds a lot of variety in one spot. “Long Hill has three distinct areas,” she says. “It has a wild meadow, meticulously curated and manicured gardens, and a lot of wooded trails. The diverse landscape of Long Hill is like a dreamscape for any plein air painter. It has something for everyone.”

The experience of working from gardens and a manicured landscape made Bittner question what is natural. “Is one thing more natural than another because it doesn’t have as much human interference?” she asks. “Long Hill allows anyone who’s entering the property to think about this, and it’s something that’s at the center of my practice as a plein air painter.”