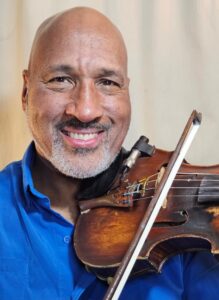

When David Eure plays his violin, its fingerboard dusted with rosin, he’s constructing a masterpiece of texture and inflection. In performance, he says, “Your audience is your canvas, and you’re painting sound over them.”

Eure was born in Boston to an educator mother and a father who wrote editorials for the Boston Globe. “We went to virtually every NAACP march,” he says. When he was six, he marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Boston. It was a time of revolution, says Eure, and he was surrounded with the concept of “Black excellence.”

Eure’s parents loved jazz. Miles Davis and Ella Fitzgerald were the soundtrack to his babyhood. He started on violin at seven, at the New England Conservatory: first, Suzuki and three years later, jazz. Gunther Schuller and Ran Blake founded NEC’s “Third Stream” program in 1972; it introduced children to both European classical music and American jazz traditions. “It was just wonderful,” says Eure.

“Physically,” he says, “there is no difference between a classical violin and a jazz violin.” In both genres, there are rules of technique: “Fingerings, shifts, bow strokes — everything from martelet to staccato to spiccato.” In jazz, he says, “We incorporate all of those techniques and even exotic ones, like left-hand pizzicato.”

But metaphysically, a world of difference separates the two. “It’s all about how you play it,” says Eure. A classical violinist is “reimagining what the composer intended,” he says. “In jazz, we are musical storytellers. We can conjure a story out of thin air and make it resonate in your soul.”

Eure will perform with pianist Lee Adler at Wellfleet Preservation Hall on Wednesday, June 18 in honor of Juneteenth, which commemorates the day that enslaved people in Texas heard that they were free.

Eure has performed a Juneteenth concert in Wellfleet for several years. In the past, he’s delved into ragtime and blues of the ’30s and ’40s. This year, he says, they’ll play songs from the ’70s and ’80s by Miles Davis, Stevie Wonder, Kenny Kirkland, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, and Alice Coltrane.

Some might consider it “their grandparents’ music,” says Eure. “But there’s nothing old about it. It’s still as vibrant and important as it ever was.”

He loves performing for kids, who he calls “unpolished gems…. They’re not conditioned to react to your music,” he says. “It stimulates their imagination; their outlook; their attitude.” He doesn’t care if there’s a baby crying in the back of the hall, either. “I’ll play to that kid any day of the week.”

Eure now lives in Natick and has been teaching in the jazz department at NEC for 25 years. A violin can speak, he tells his students, and jazz violinists “speak in squeals and hollers.” The violin, he says, is the instrument that sounds closest to the human voice — besides the saxophone.

Eure’s own voice emerges from the violin, shimmering, sliding, snarling in turns with the flick of a finger or the snap of a wrist. “I can make it sotto voce, a soft voice; I can make it speak; I can make it bark; I can make it thump,” he says. “I can make it a bass, growly thing, or I can go up to where a soprano lingers.”

Eure doesn’t just play jazz. “I’ve played every kind of music under the sun,” he says. In his conservatory studies at the Hart School in Westport, Conn., from which he graduated in 1980, he gravitated to romantic composers like Ravel, Debussy, and Fauré. “The romantics started to get it together,” he says. “They were like, ‘Oh, man, we’ve got to make this lush and syrupy thing, and it’s gonna be sensual and wonderful.’ ” They sang through their music, he says, just as jazz musicians do.

Eure has played Irish traditional music, Armenian music, and bluegrass. “You name it, I’ll be there,” he says.

The beauty of jazz lies in that breadth of imagination, says Eure. “You try to stretch the instrument beyond what was originally intended. I can make something sound like it was made 100 years ago or 10 years ago.”

Arranging, he says, is a process of deconstruction and revision. “You think in terms of art, texture, color, form, architecture,” he says. “I will never play the same tune the same way twice.” Improvisation, he says, “is where the magic occurs.” Adler is a good partner for improvisation, he adds — they’re both “old fogies” with youthful outlooks. With enough spice added, Eure says, jazz “is like jambalaya.”

To be a musical storyteller, he tells his students, is to be in constant conversation. On his violin, “I can have different characters,” he says. “I can have a dialogue with myself — I can do double stops, triple stops.”

The stories Eure tells — tragic, energetic, political, inspiring, rageful — must be so compelling, he says, that listeners can close their eyes and feel the music without watching the performer at all. “The music has to speak for itself,” he says.

A World of Pure Imagination

The event: Violinist David Eure and pianist Lee Adler in a Juneteenth concert

The time: Wednesday, June 18, 5 p.m.

The place: Wellfleet Preservation Hall, 335 Main St.

The cost: $28 plus fees at wellfleetpreservationhall.org