Provincetown photographer William P. Hamlin uses weaving, an ancient artisan technique, to create his photographic prints. While studying at New York University in the 1980s, Hamlin had the idea to weave two photographs together. At first, he dismissed the result. “I thought, that’s just a placemat,” he says. “I didn’t really see the value in it.”

Something about the process intrigued him, however, and in the ensuing years Hamlin went back to the idea. He has since made several series of woven photographs — portraits, scenes of water, and, most recently, flower arrangements. His current series of flower portraits will be on display at Provincetown’s Schoolhouse Gallery in an exhibition opening on June 6. He has shown his work there since the gallery’s inception in 1998. In 1999, he moved to Provincetown from New York City and currently works from a studio off Shank Painter Road.

Hamlin’s images are about more than just the figures and objects they depict. They are about time.

“When we photograph things, it captures just a nanosecond of time,” he says. “The question is, how do I capture the essence of time in a photograph?” In this pursuit, Hamlin must contend with the constraints of photography, he says, including the flatness of the photo paper and the limited depth available in a photograph’s image.

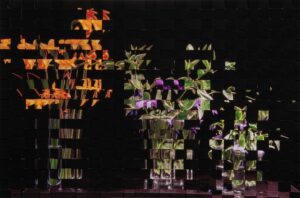

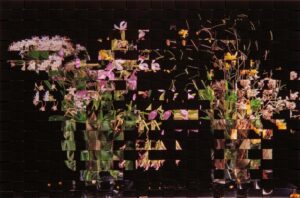

To create works like Sweet William and Basil and Daffodils and Periwinkles, Hamlin pieces together two different but similar photographs. He arranges flowers in vases with an eye to composition and photographs them in his studio when they are in full bloom. He then lets the arrangement sit before photographing it a second time when the flowers have decayed. This time, he lets the flowers droop and bend naturally without altering their position. The result — a composite of the two photographs — captures the progression of time and the lifecycle of the flowers.

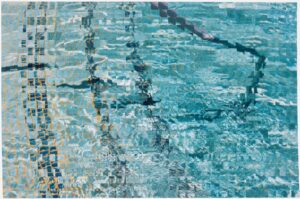

In other photographs, Hamlin uses weaving to suggest movement. In his early woven pieces, he used two copies of the same photograph but placed them off register from each other to distort the image. One of these pieces, Pool Railing With 3 Steps, expands the capacity of a photograph to depict the experience of looking down into water. The colors of the steps and the railing are doubly broken up — first by the movement of the water and second by the slicing and weaving of the image. Color, shadow, and light swirl together as the viewer’s eyes move constantly back and forth to take it all in.

To create the weaving, Hamlin cuts the printed photographs into strips, one vertical and one horizontal. He glues all the pieces at one end and then starts to weave. For some images, he weaves all the verticals first and then the horizontals, but at other times he plays around with the order, resulting in even more complexity.

Hamlin grew up in Connecticut before moving to New York City to study photography. At school he shot black-and-white film and was influenced by Cubism but also had his eyes on contemporary artists. He began to experiment with color photography and expand on his idea of the woven image. David Hockney’s photomontages, Lucas Samaras’s collaged polaroids, and Chuck Close’s pixelated portraits were all inspirations for Hamlin’s early photographic weavings.

Process and play are still important components of his studio practice. When Hamlin shoots, he has a very small amount of light on his subject.

“I usually do long shutter speeds,” he says, “and I have music on low. It’s quiet and still.” He admits that he could create a similarly dramatic effect in Photoshop, but the tactility of the process is important to him. “My experimentation is all with the hands-on process,” he says.

Once he has the two photographs he wants, Hamlin starts to play. This is when most of the decision-making happens. He often makes several woven versions of an image before settling on the one that works best. Do you want to see more of the vase, or does it just drop off into blackness? Is it more interesting to see the daffodil in full or only a small part? How much repetition should there be? Hamlin notes that there are certain parts of each version that he really likes, but usually one works better than all the others.

In addition to their explosive color, Hamlin’s flower portraits also have generous dark spaces which provide visual rest amid the busy, shuddering movement of the flowers. The black backdrop he uses in the studio adds a nocturnal element to the work. “I find the darkness really peaceful,” Hamlin says. “Some people are afraid of the dark, but I think it’s soothing.”

The final results bear evidence of the artist’s hand, and the weaving of two pieces of paper together inevitably gives the artwork more physicality than a single print. It begins to take on the characteristics of an object — taking up space while also suggesting the ephemerality of time.

In addition to the passing of time, Hamlin’s flower portraits also conjure ideas about beauty, decay, and the inability to fully capture an image. The weaving obscures parts of his subjects. As viewers, we search for the subject: we are forced to continually shift our view, attempting but never quite succeeding to complete the picture.

While a photograph of a beautiful bouquet might be taken in quickly, these images require the viewer’s time and engagement to be fully experienced. Hamlin emphasizes that he never wants to sound just one note. He asks of himself and his work, “What do you want to tell me or show me other than these beautiful objects of nature?”

About Time

The event: An exhibition of woven photographs by William P. Hamlin

The time: June 6 to July 8; opening reception, Friday, June 6, 6 to 8 p.m.

The place: Schoolhouse Gallery, 494 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free