“Golden ages” are rarely golden for everyone, especially in film history. The era referred to as “classic Hollywood” roughly coincided with the Production Code, a set of guidelines developed by the Motion Picture Association of America that from 1934 to 1968 directed studios to self-censor their films for material deemed inappropriate. Under the Code, explicit displays or implications of errant sexuality — including homosexuality — were verboten.

That era’s censorship and social repression prompted gay activist Vito Russo to write his 1981 book The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. “As expressed on screen,” he wrote, “America was a dream that had no room for the existence of homosexuals.… When the fact of our existence became unavoidable, we were reflected, onscreen and off, as dirty secrets.”

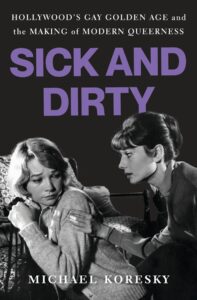

Some critics, influenced by Russo, regard many Code-era films as deserts for queer representation, either because they erased gay existence entirely or presented queer-coded characters as uncomfortable stereotypes: the predator, the effete friend, the “tragic lesbian.” But where other critics see a desert, author Michael Koresky sees an oasis. In his just published book, Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness (Bloomsbury), Koresky argues that many Hollywood classics deserve a second look by audiences interested in desire, taboo, and sexuality: movies like Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), Vincente Minnelli’s Tea and Sympathy (1956), or Dorothy Arzner’s Dance, Girl, Dance (1940). On Saturday, June 7, Koresky will be in conversation with editor Aaron Hicklin at Provincetown’s Hawthorne Barn in a Twenty Summers program.

In examining these classics, Koresky, senior curator of film at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York, writes that some queer representations deemed “problematic” by contemporary standards are less simple than they seem. The Code may have rendered homosexuality unspeakable — but cinema is a visual medium, and Koresky persuasively shows how artists gay and straight toyed with Hollywood’s sexual fearmongering and molded it into art. “An ironic result was that this era of Hollywood would prove to be one of surpassing sensuality,” he writes, “of desirous men and women whose attractions and motivations would be clear to anyone actually keeping their eyes on the screen.”

Central to his argument is The Children’s Hour, a 1934 play that was adapted for the screen twice by the same director, William Wyler, in 1936 and 1961. The drama, written by Lillian Hellman, is about two women, Martha Dobie and Karen Wright, who run a girls’ school together until a resentful student falsely accuses them of having a lesbian relationship. The dual adaptations are useful for Koresky’s purposes — they illustrate what was shown in the restrictive ’30s compared to the early ’60s, when the Code was more loosely enforced.

Hellman’s play is explicit about the women’s purported relationship. But the 1936 adaptation, titled These Three, does away with any suggestion of lesbianism by tossing a man into the mix: the child’s accusation in that movie is of infidelity rather than homosexuality. Koresky takes his book’s title and cover image from Martha’s confession in Wyler’s 1961 film, which stars Shirley MacLaine and Audrey Hepburn and is much more faithful to the play. After the women lose their school and nearly everything else, Martha (MacLaine) confesses to Karen (Hepburn) that the accusation has a grain of truth. “I have loved you the way they said!” Martha says. She can’t stand feeling “so sick and dirty.”

Koresky’s focus on The Children’s Hour helps him trace other common themes in queer cinema — rejection, shame, the fear of being “sick” and unloved — and why he thinks the censored queerness of classic Hollywood is especially adept at speaking to them. The idea for his book, Koresky says, came after he screened the 1961 film for NYU undergraduates while he was an adjunct professor. He worried the movie would strike the students as outdated, but their emotional reaction to the film’s controversial ending — Martha hangs herself — surprised him.

In one sense, Koresky is taking the remit of The Celluloid Closet forward: correcting the record when it comes to homosexuality’s erasure from American culture and celebrating the queerness that did survive censorship. But whereas many in Russo’s generation reacted to the repression in the Code with righteous rage, Koresky suspects the emotions in those films merit further exploration: feelings of rejection, shame, and guilt are as resonant for a queer audience today as one in an earlier era, if not more.

Koresky, who lives in Brooklyn and has spent winters in Provincetown with his husband since 2006, has made a career of studying gender and queerness in film. Cinephiles may know him best as founder of Reverse Shot, an online film magazine. His first book, Terence Davies, was a monograph on the late British filmmaker who revolutionized depictions of queerness and memory on screen. He followed that with Films of Endearment, a work of criticism and memoir that argues for the aesthetic significance of 1980s studio movies about women’s lives — pictures like 9 to 5, Baby Boom, or Terms of Endearment.

Perhaps no film illustrates Koresky’s point more than Suddenly, Last Summer, a 1959 production with queerness written all over it: it’s an adaptation of a hit Tennessee Williams play, written for the screen by Gore Vidal, and directed by All About Eve filmmaker Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Katharine Hepburn stars as Violet Venable, a rich New Orleans dame who has lost her beloved son, Sebastian, a young poet heavily implied to be closeted. The only witness to his death — allegedly caused by a heart attack — is Violet’s troubled niece Catherine (Elizabeth Taylor). Violet tries to get Catherine lobotomized, claiming her niece’s insanity leaves her no other choice. Her real intent, though, is to erase Catherine’s knowledge of the truth about Sebastian’s death. (Memorably, the incident is revealed to involve some of Sebastian’s jilted male lovers in a fictional Spanish beach town called Cabeza de Lobo.)

Sebastian is a structuring absence in the movie; even in flashbacks, his face is never shown. He’s portrayed as something of a selfish predator, exploiting Catherine’s good looks to procure men. With its gay villainy and veiled eroticism, Suddenly, Last Summer is the kind of movie that drew Russo’s ire in The Celluloid Closet. He called the film “the kind of psychosexual freak show that the Fifties demanded” and objected to Sebastian’s portrayal as a “faceless terror.”

But in searching for more productive queer resonances, Koresky finds that the movie bears fruit. Suddenly, Last Summer is “abuzz with exciting frissons of homoerotic desire and genuine transgression,” he writes. Precisely because the film is not an easy sell for those seeking affirmations of gay life, he argues that it surveys an “unseen internal landscape [of] frustration, unbelonging, melancholy” — one that reflects the original play and Williams’s own struggle with his gay identity.

“Art doesn’t have to be good for you,” Koresky writes in Sick and Dirty — an axiom well heeded while watching Suddenly, Last Summer or any of the other thorny, beguiling Code-era films that he presents. “Cinema isn’t a shorthand for morality,” he adds, “just as, despite its legions of religious worrywarts, it was never an expression of a culture’s immorality.”

Dirty Secrets

The event: Michael Koresky and Aaron Hicklin in conversation

The time: Saturday, June 7, 1 p.m.

The place: Hawthorne Barn, 29 Miller Hill Road, Provincetown

The cost: $20 suggested donation at 20summers.org