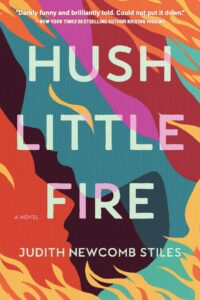

Judith Newcomb Stiles is a potter, teacher, and writer whose family has lived in Wellfleet since the days of the Pilgrims. In her new novel, Hush Little Fire, published by Alcove Press this month, she tells an intergenerational tale of adoptions, abortions, and long-simmering secrets in an Outer Cape community, drawn from her own experiences, she says, but very much a work of fiction. “This twisty novel will be a good option for those looking for an unconventional and thematically potent mystery,” said Kirkus Reviews.

The following excerpt follows “Birdie,” a young woman who is just discovering that there can be more to life than raising a family or pleasing a husband. —Daniel Waite Penny

I am certain the Old Ladies Gossip Militia was founded on the Mayflower in an informal, unorganized way when the women had time to talk while cooking, or sewing, or swabbing vomit off the deck into the sea. It’s not in a history book or anything, but our women became the historians of all things Cape Cod for centuries without writing anything down. No membership fees or formal meetings, just information passed through the grapevine, was the best way to keep secrets from becoming too secret.

An anonymous member of the 1963 Old Ladies Gossip Militia was caught blabbing gossip about us Newcombe girls again. She said to anyone who’d listen that my sister-in-law, Clara Newcombe, and “Birdie Brains” (she called me that!) were spotted driving to Provincetown for art classes, and it was confirmed that neither of us housewives had a valid driver’s license.

Clara was teaching me how to drive a stick shift without any help from a man. She drove her husband’s truck with me shotgun while we argued about if it was tacky, maybe premature, to wear my new black beret to art class.

“Only artists in New York City wear berets,” Clara said, turning down the radio, which was blasting President Johnson’s speech at headache level.

“Turn it off! I can’t think when he whines.”

“Yessirree!” I grabbed the knob on the radio so hard it popped off.

“The president is a nincompoop.” Clara gunned the engine and checked her lipstick in the rearview mirror. She was pushing seventy miles an hour all the way to Provincetown so we wouldn’t be late for our class with the cute painting teacher, who happened to be French.

The inspiring art teacher had changed everything for us, and we felt like real artists when we discovered how to observe and interpret the world in new ways. The seashore and sunsets were the subject of art classes in the summer, but the Cape Cod housewives of winter like us were introduced to the landscapes that were hiding in our minds. Besides, it was hard to get students to paint snow and flat gray skies, the dreary winter landscape of the Narrow Land. December was a rough time for everyone, and Antoine and the professional artists in Provincetown had bills to pay too, so they gave discount lessons to the local ladies, and I knew they only did that so they wouldn’t starve.

In our first class, just before the water break, Antoine leaned over Clara’s shoulder, his arm casually skimming her breast as he told her that the sky didn’t have to be blue.

“You can paint the sky any color you want,” he said as he added a dab of red to her sky, his elbow wiggling each breast. That was probably the exact moment in time when he and Clara began their ravenous affair. And observing that red dab of paint land on Clara’s flat blue sky catapulted me into my own ravenous spell of oil painting. It was also the moment when the sword fight of dos and don’ts broke out in the center of my mind. Do this. Don’t do that. Something I heard all my life. But soon after the dab of red paint, I killed the bossy voice in my head and painted all kinds of Cape Cod scenes that were staked out in my memory. I liked to paint by the stove in my kitchen, and I often went to bed smelling of turpentine.

In Provincetown, Clara was so relieved to be away from her young son, Jimmy, who was a tornado of energy, driving poor Clara nuts. Every Saturday I kept an eye on Jimmy when Clara was off somewhere, screwing the painting teacher. Clara’s extracurricular activities were fine with me because I knew Clara was lonely, living at home with a five-year-old and no adults to talk to. The affair with Antoine was not unusual for a woman who had to endure winter on the Narrow Land with a husband off at sea. People did lots of crazy things stuck under that gray sky day after day. Besides, Clara’s marriage to Big James was like being married to a ghost.

The latest trip, he supposedly was on a tanker in the Red Sea, somewhere near India or Africa. Each time Big James came back, he brought a cheap present for his son, like a plastic water pistol from Nova Scotia, and he made hollow promises that Jimmy could be the cabin boy on the next trip. I got in a loud argument with Big James, yelling at him that he must never promise that to Jimmy again.

“Every time you come back, you promise the poor boy he can come with you. Jimmy will be a cabin boy over my dead body,” I said, trying to control the hissing in my voice.

“Why not?”

“I heard what cabin boys did in the olden days.”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about. Cabin boys do chores and learn about life at sea.”

“No way! A little boy out at sea for months with a bunch of horny old sailors. And what about school?” Big James just laughed, which made his eyelids quiver. But I knew, and all the elderly women on Cape Cod knew, that in the olden days, cabin boys did double duty sexually pleasuring the sailors who got too pent up at sea. Sailors and pirates who were much too far away from their wives and taverns, anxious to stick it in a hole somewhere. Big James adamantly denied any such thing ever happened on ships, but I couldn’t help noticing how sheepish he looked as he stuffed the peanut butter sandwich into his mouth — the whole entire sandwich in one fibber’s bite.

It bothered me a lot that random men — men like Big James — had a knack for invading my thoughts uninvited, especially in art class when the painting teacher droned on and on about famous men painters from France we should admire. I wished Antoine would shut up because I was dying to ask Clara what she thought of the lady from New York who went undercover dressed up as a Playboy Bunny.

“You mean Gloria Steinem?” whispered Clara when Antoine left the room.

“Yeah, that one. I really like her hair. I love the extra streak of blonde in the front.”

I added a streak of yellow to my ocean waves. The coincidence was thrilling.

“I don’t know, if she doesn’t bleach that streak properly, she’ll look like a skunk. Just one streak is enough,” Clara whispered, frantically applying more lipstick. “She’s just another rich bitch from the city telling us what to do. Like don’t wear a bra. Oh please, that would make my boobies sag.”

I liked to agree with Clara on most issues, because it was easier to agree than argue with my only friend. I didn’t want to ruin things with Clara. But what I really wanted to say to Clara, and all the other gossips in town, was Gloria Steinem has gorgeous hair. She doesn’t look like a skunk. And Gloria most definitely has a point. The way she talks — got me thinking that I have a right to paint in my kitchen whenever I want!