In one of Susan Lyman’s sculptures, Washashore (Survivor), a white cedar tree is truncated just above the roots, like a figure cut at the torso. It stands upright, supported by roots that look like dancing legs. Unlike many of her other sculptures, which are marked with lines or dots, this one is stained only in a pale, warm color. The sanded wood is smooth. It looks alive, as if it could jump off its pedestal. But it’s clear this is also something dead: there’s violence lurking in its truncation and excavation from the earth.

Lyman has been working with trees as subject, material, and muse since she came from Michigan to Provincetown in 1981 as a Fine Arts Work Center fellow. Here, she began collecting masses of invasive bittersweet vine and fallen limbs. Lyman’s current exhibition, “The Cadence of Uncertainty,” is her first solo show at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

The works on display through May 11 are mostly from the last decade and show the breadth of her art practice, which includes painting and sculpture. She makes sculptures primarily in her Provincetown studio and turns to painting when she’s in Arizona or Michigan, where she spends part of each year. Lyman’s work engages with these varied geographies and grapples with the interdependent and often problematic relationship between nature and humanity.

Some of Lyman’s paintings explore disease as a subject. In Covid at Lago Titicaca, she paints the South American lake and its surrounding landscape in lurid colors: deep blues, autumnal oranges, and fleshy pinks. A green image of the Covid virus is transposed onto the landscape like an alien intrusion. Other viral shapes infect the painting. Pink blobs are obscured under the land and float in the sky.

Lyman visited Lake Titicaca in 1981 with Ken Stebbins, whom she was dating at the time. In the intervening years, they married other people but reunited after both lost their spouses; they married four years ago. In Covid at Lago Titicaca, Lyman evokes the cyclical and interconnected nature of existence through imagery that addresses personal history, time, nature, infection, a global pandemic, and a specific landscape.

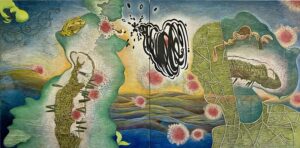

Viruses also show up in Harbinger as red orbs. Lyman’s techniques are as expansive as her subjects — like many of her paintings, this one was derived from a collage. A swirling mass of black lines sits at the center of the composition, which stretches out to incorporate decorative pencil drawings, topographic maps, and deep space articulated through hills folding into each other and rendered with strands of bright color.

A collage-like quality links Lyman’s paintings and sculptures. It resounds with the legacy of surrealism and opens avenues of association between subjects, images, and visual languages. In Charrue en Lotus Attaché, Lyman begins with a small log but manipulates its branches. She connects other branches to the originals, attaching them at right angles to create a box-like form that the log hovers within. The form has two ends — branches painted red — that suggest the head and tail of a snake. What began as a tree turns into something geometric and animal-like.

In other sculptures, Lyman recreates the body in associative gestures that are often humorous. Litany was made from bald cypress knees, part of the root system of the trees that sticks up out of the water in wetlands. Lyman caresses the surface of each form: sanding, staining with wood dyes, accentuating the growth lines with acrylic paint, and dotting with a wood-burning tool. The forms are arranged together, but each has its own personality. Their anthropomorphic quality is further underscored by the way Lyman manipulates the wood to make its wrinkled growth lines look like sagging flesh.

Although Lyman’s sculptures often suggest bodies, they’re not illustrative. They remain ambiguous and abstract and recall many things at once: appendages, genitals, growths, tumors, and forms from the natural world, like sea sponges and fungi.

In Lyman’s work, erotic and diseased forms are like two sides of the same coin: one generative, the other destructive, but both part of the cycle of existence. In Botanical Theater #20 (repurposed), Lyman works with the vertical line of a tree trunk, but all the action happens at the ends. At the top, a conglomeration of assembled sticks appears as an amphibious creature balancing on the structure. At the bottom, a bulbous, root-like base sprouts an egg-shaped appendage. In Coy, the forms are emphatically erotic, and somehow at once male and female. Meredith, a gently arching form recalling the work of Romanian artist Constantin Brâncuși, is another one of the exhibition’s sensuous sculptures with its flushed pink and rounded shapes.

In one of the most recent works in the exhibition, Cone of Uncertainty, Lyman articulates a vision that is both sensual and ecological and shows the inextricable link between the destinies of humans and nature.

The piece is constructed from branches that Lyman arranged into a downward swirling form. In the exhibition catalog, she states that the sculpture is “a tree not grounded but made uncertain by natural or manmade forces.” It’s informed by climate change, natural disasters, and wildfires. An orange line of branches snakes through the chaotic, destabilized form like a flame. Black birds, calling to mind endangered North American species, nestle in the inverted tree and sit on the wall behind the sculpture.

This work sounds an alarm that echoes through some of Lyman’s other recent work, including a series of paintings about the ecological and moral crisis at the border between Mexico and the U.S. But it’s also a beautiful sculpture, sensitively rendered. Beauty and the sensuality of form seem to freeze this inferno and suspend destruction. In Lyman’s hands, art is like a tree sprouting from the scorched earth. It’s a gesture of defiance and hope: a life force that contends with the antagonistic force of entropy embedded in our bodies, our politics, and nature.

Life Forms

The event: Susan Lyman’s “The Cadence of Uncertainty”

The time: Through May 11

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: General admission $15