Peter Beinart, one of the most prominent public intellectuals on the American Jewish left, wrote in July 2020 that he had changed his mind about a “two-state solution” to the never-ending conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. “It’s time,” he wrote in an opinion piece for the New York Times, to “embrace the goal of equal rights for Jews and Palestinians. It’s time to imagine a Jewish home that is not a Jewish state.”

Beinart hasn’t altered that view in the ensuing five years. He has written with even more urgency as Israel pursues its war in Gaza and the U.S. government is arresting student visa-holders who have expressed support for Palestinians.

Beinart brings a broken heart to his latest book, Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning (Knopf, 2025). He frames the book as an honest conversation with Jews who may not agree with his condemnation of the war. To sustain this intimacy, he employs the pronoun “I” and adjective “my” for himself and “you” and “your” for his guests, other Jews seated around a dining table at Shabbat, the Friday evening meal.

“I think about you often, and about the argument that has divided us,” he writes in the opening pages of Being Jewish. “I know you believe that my public opposition to this war — and to the very idea of a state that favors Jews over Palestinians — constitutes a betrayal of our people. I know you think I am putting your family at risk.”

How long, he wonders, can those at the table stay in the conversation he would like to have, especially if he expresses his opinions. “It’s hard to talk so frankly today.”

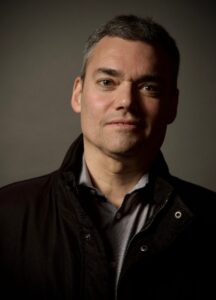

Beinart has long been interested in history and politics. He studied both as an undergraduate at Yale and then as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, where he sharpened his focus to foreign policy. Of his four books, Being Jewish is the most personal. He intends the book for Jews but has anticipated the needs non-Jews will have as they read it. For example, he uses the term “Hebrew Bible” instead of Torah and recounts the story of Purim, which most Jews will know.

Beinart demands that Jews stop seeing themselves as victims and, instead, faithfully tell Biblical and historical stories that show Jews as oppressors and not just the oppressed.

He doesn’t minimize experiences of anti-Semitism, which he describes as “among the most resilient and destructive forms of hatred in history.” He is angry at non-Jews, especially on the left, who have been insensible to the grief Jews worldwide have experienced from Hamas’s massacre and hostage-taking on Oct. 7, 2023.

But Beinart also criticizes Jews who refuse to hold Israel accountable for oppressing Palestinians and taking their land. He extends this criticism to contemporary Israeli policies in the West Bank and Gaza, which he believes provoked Hamas’s attack. This is where the conversation around Beinart’s metaphorical Shabbat table breaks down.

“Soon after the massacre, one of our closest family friends asked my wife whether we believed that Israel bore any responsibility for the carnage,” he writes. “She answered yes. He said he would never speak to us again.”

Beinart describes Israel as an apartheid state that should be held responsible internationally. He wonders why Jews can’t see parallels between Israel and South Africa, Ireland, and the American South, where destroying oppression led to a burgeoning of peace.

In some of the book’s most forceful and elegantly argued chapters, Beinart dispatches arguments many Jews make to justify the creation of the Jewish state. He denies the legitimacy of Israel’s current war, which he calls immoral. Some readers may feel inundated by facts. Others will savor the ways Beinart buttresses his work so that his thinking extends beyond opinion into closely argued reasoning. The most intellectually curious of Beinart’s opponents will appreciate an opportunity to see why he is concerned that Jews who endorse the war in Gaza “shrug, if not applaud” in response to Israel’s actions.

Beinart is not persuaded by the retelling of stories of Jewish victimhood. He worries that those who don’t agree with him about the war “block out the screams” of Palestinian victims. He calls out the American Jewish Committee and the Anti-Defamation League for having “traded on our solidarity to justify starvation and slaughter.”

That solidarity works two ways, Beinart writes. It is the driving force that has probably allowed the Jewish people to survive. At the moment, though, he argues that the most manipulative of his opponents play on the perception of solidarity to shun Jews who disagree with the Jewish state — not the Jewish people.

Beinart keeps kosher and sends his children to Jewish day schools. In the videos he records for his Substack newsletter, he shows himself seated at a desk in front of bookshelves lined with red volumes of the Talmud, a compendium of Jewish law.

“How does someone like me,” he writes, “who still considers himself a Jewish loyalist, end up being cursed on the street by people who believe Jewish loyalty requires my excommunication?”

Beinart is fighting excommunication as it applies to students on American college campuses. “American Jews don’t need to search for the hidden antisemitism in every nineteen-year-old anthropology major,” he writes. “We don’t need to get decent people fired.… We don’t have to ally with MAGA thugs because racists are Israel’s most reliable friends. We don’t have to disfigure our communal institutions by suppressing open debate. We don’t have to close off a piece of ourselves and barricade it from our best qualities — kindness, compassion, fairness — because that’s the only way we can defend what’s being done in our name. We can lay down the burden of seeing ourselves as the perennial victims of a Jew-hating world.”