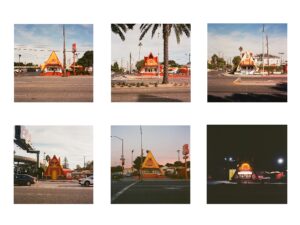

Fine Arts Work Center visual arts fellow Ian Page arrived in Provincetown last fall from Los Angeles, where he had become interested in Wienerschnitzel, a fast-food chain that sells hot dogs from A-frame buildings. The structures embody “a type of Southern California goofy architecture,” Page says. Paradoxically, he also views the restaurants as representative of “an American longing for European authenticity.” Photographs of the restaurants are displayed on one wall of his FAWC studio.

In November, on election day, he drove around Los Angeles from sunup to sundown photographing Wienerschnitzels. He had done the same thing four years earlier. It’s not obvious why he photographs these restaurants on election days. Surely there’s a political analogy at work, but Page doesn’t spell it out for the viewer.

“I have a tendency of being cryptic,” says Page. “I’m not intentionally withholding, but I’m also not overexplaining. I don’t want my meaning to be the only one, and I don’t think that my meaning is the most important one. The audience has some responsibility for making meaning. That’s part of a relationship that has integrity.”

Page belongs to a vanguard of artists — one that has always existed — that is fundamentally concerned with advancing the language of art.

Walking into his studio, one steps directly onto a sheet of linoleum printed to look like bricks (an object that’s inherently duplicitous). The word “since” is cut into the surface twice. At first, one might think it is an entrance mat. Upon further observation, it seems like a work of art. Page doesn’t mind the confusion — in fact, it seems purposeful. Page says he’s not “malicious” or “trying to mystify someone on purpose,” but there’s an element of play at work in his art practice that intentionally destabilizes the viewer and demands active engagement.

Take, for example, his recently updated website (ianpage.net). When one visits the site, it automatically downloads a text he has written onto the viewer’s computer. “I make slightly antagonistic websites to simulate the experience that you’re doing something when you’re moving around in these images,” Page says. “It’s not just pure consumption — it responds to you as well.”

The site scrolls through Page’s postings on a 24-hour cycle, so you can see only what’s available at the moment of access. Elements of the website serve as documentation of previous projects, but there are also images of things like consumer packaging and storefronts that feature the word “since,” as in “since 1884.” These pictures — along with the entrance mat to his studio — reflect Page’s fascination with the dual meanings of “since.”

“It goes from defining a prepositional distance in time to being a kind of rationale, meaning ‘because,’ ” says Page. “That word seems to represent the constitutional quality of our American minds that invokes the beginning again and again. That beginning guides us all the time.”

The website introduces these intellectual concerns and becomes an artwork in and of itself. “I think of my website as something that embodies an aspect of my work,” Page says, “but also acknowledges its limitations in translation.”

Page grew up mostly in Madison, Wisc. He started making Super 8 films in high school, and later he double-majored in cinema studies and Latin at Oberlin College. While there, he created a pirate TV station for his senior project.

“That set up a pursuit of finding the edges of things, of what’s legal, of where boundaries are,” says Page. After graduating in 2008 and moving to Pittsburgh, he continued in this vein as a participant in a sprawling art collective, the Miss Rockaway Armada. The semi-utopian group built fantastic-looking boats that traversed rivers. Page became interested in the ways that rivers serve as America’s flexible, difficult to secure boundaries. He also began to consider the “performance of utopia” (and the indistinction of those two things), which would remain a consistent theme in his artwork.

Page says that the “tip of the pyramid,” where his political philosophy and art practice converge, is an interest in “environments that demonstrate a fictional quality but also something real.” The Miss Rockaway Armada created elaborate productions, but it also formed a real community. The group proposed certain ideas about nonhierarchical leadership, but Page noticed that it was difficult to maintain this structure.

He sees parallels in the history of utopian movements in America. “On one level, there’s this sort of outward facing legitimacy,” he says, “and then there’s an inward facing operation that often can never be explained.”

Back in his FAWC studio, it’s not always clear how Page’s theories align with the objects he makes. In one corner, he’s making perfume. Nearby, there’s a rack he might use to display some of his homemade apple and hibiscus wine. Most of the floor space is occupied by rollers from a wallpaper facility in Hyannis that closed in the 1960s — Page bought them on Craigslist when he first arrived in Provincetown.

“A really functional way for me to get into a new place is to go through its garbage,” he says. In a recent group exhibition of FAWC fellows at PAAM, Page displayed the rollers in a three-dimensional grid. He plans to expand the sculpture for his showcase exhibition.

For Page, the objects represent a “lapsed mid-20th-century aspirational quality.” The rollers are remnants of middle-class efforts at home decoration — “the dirty industrial backside of this fictional life,” he says. When he started assembling them into structures, he noticed they “started to take on a kind of punishing quality,” appearing almost like a torture device. The meaning of the work is fluid and exists between the viewer’s impressions, the form itself, and Page’s intentions, but even those intentions are negotiable.

“I don’t say what my intentions are ahead of making a lot of work, and it takes me a couple of years to figure out why I made certain choices,” he says.

Winemaking is a new project for Page, and he’s not sure if it’s art yet. “What counts and doesn’t count as art is such an interesting part of the big negotiation with oneself,” says Page. “I don’t know why the wine isn’t art yet, but that’s because I don’t necessarily have a precedent I’m following.”

Other vanguard artists have acted as springboards for his creative inquiries. When making his website, he observed artists like Cory Arcangel and Joshua Citarella, who were using the internet as a creative medium. They provided him with something to build on.

If and when Page figures out how to frame winemaking within his art practice, he hopes it will set a precedent for others.

“Maybe it will give another artist more ideas,” he says. The process of artmaking is like building a utopia. “You have to play act the world you want to live in,” says Page, “and that at least opens up an opportunity for that world to emerge.”

Fellow Fridays

The event: A showcase and reading with Zeinab Shahidi Marnani, Ian Page, Parker Hobson, and Matthew Wamser

The time: Friday, April 4, 5 to 8 p.m.

The place: Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free