There’s a big bowl on Provincetown artist Gail Browne’s dining table, but it’s not full of fruit. The dish contains marbled ceramic balls and horseshoe crabs — paperweights.

“It’s what I do with clay scraps,” Browne says. The horseshoe crabs, with little spiny ridges, look almost lifelike. To make a mold for them, “I got a tiny horseshoe crab, and I cast it in plaster,” she says.

All of the pieces were done using the terre mêlée technique — the phrase means “mixed earth” in French. The labor-intensive process involves layering different colored clays, rolling the sandwiched clay out, cutting it into strips, and braiding the strips together. Once it’s rolled out again, the clay resembles marble.

There’s an element of spontaneity in the process. “You never know what’s going to happen or how it’s going to look,” Browne says.

To make each color, she starts from scratch with powdered porcelain. Using mineral oxides, she adds color proportionate to the clay. For six pounds of clay, Browne might add four ounces of colorant, she says, depending on the intensity she wants. From there, she hydrates the clay and rolls it out into a slab. “It’s like making a cake,” she says.

Terre mêlée is hard work. When she was first learning the technique, Browne found that the different colored clays fought against being twisted together. The pieces would split and crack while drying.

“The molecules of clay like to be organized,” she says. She points to the blue and white striations on one of the terre mêlée horseshoe crabs. “See how complicated this is? That’s hard for the molecules to accept.”

Her solution was white vinegar. A friend of hers, a former engineer, suggested that heat might help. “Not the heat of the kiln,” Browne says. “The white vinegar creates heat in the clay, and all the little molecules stick together.” She now sprays vinegar on all her pieces right after she makes them and several more times during drying.

Browne grew up in Parma, Ohio in a family of artists. At six years old, she started taking weekend classes at the Cleveland Institute of Art and eventually got her bachelor’s degree there. During college, she visited Provincetown on a summer scholarship to learn from painter and teacher Henry Hensche, who founded the Cape School of Art in 1932. Browne fell in love with this place. After graduating, Browne says, she turned down a job at the Cleveland Museum of Art to move to Provincetown, where she’s lived for the past 55 years.

Cerulean blue terre mêlée plates are stacked on steps near the bottom of Browne’s staircase — sets of commissioned dinnerware. She picks out three and holds them to the light. As she recycled the clay scraps from each piece to make the next, Browne says, its marbled pattern became less clear — the “skinny lines” became wider; the blue became lighter. Opening a nearby closet, she reveals more terre mêlée works, including trays and paper egg cartons filled with clay marbles.

She does other types of pottery, too. On a shelf at the top of the stairs sit three golden planets of varying sizes: the three, along with a fourth planet that Browne keeps elsewhere, make up a piece called War of the Worlds. The work was inspired by a metallic, oily glaze called “Cosmos” that Browne “fell in love with right away,” she says. “I thought, ‘How am I going to show this glaze off?’ ”

One shiny globe is riddled with holes; thin noodles of clay twist around another; the biggest orb sprouts bubbles. Tiny white cones, like melted soft-serve ice cream cones, adorn all three. They’re pyrometric cones, which are usually placed alongside ceramics that are being fired in order to gauge the kiln’s temperature.

“If it melts like this, it’s perfect,” Browne says, pointing to a neatly folded cone. “If it melts like that,” she says, gesturing toward a lumpy, twisted cone, “your kiln is running too hot.” War of the Worlds is a response to the shifts our world is experiencing, Browne says.

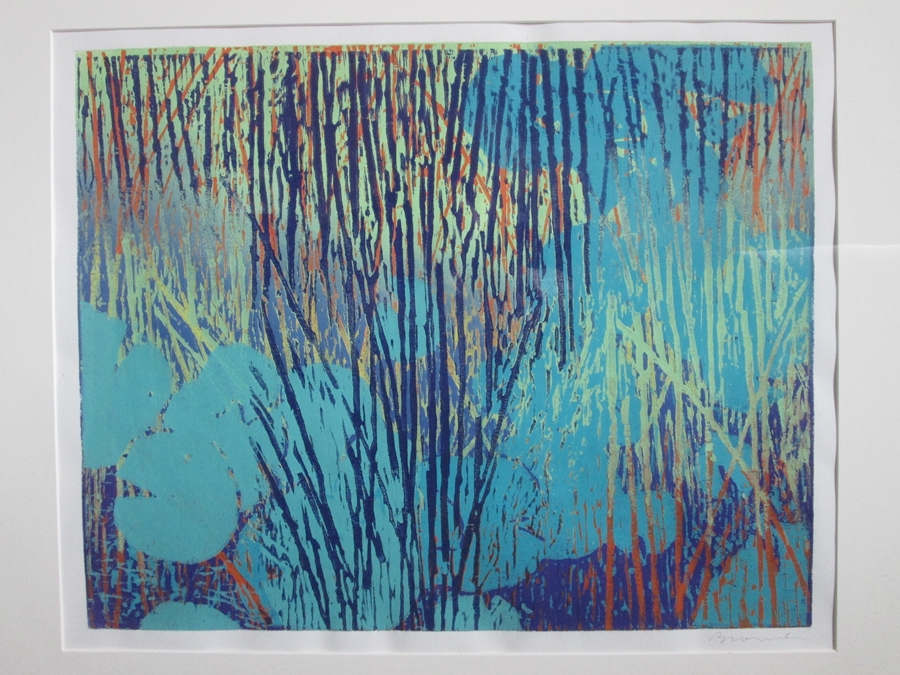

Her home is decorated with other kinds of art as well. Two large woodblock prints lean against the staircase banister. “I went through a printmaking phase,” she says. For the woodblocks, she carved designs into sections of quarter-inch plywood, which “splinters a lot, since the wood is laminated,” she says. “You get an edge that’s chewed up.” This rough quality lent itself to reed-like designs. She printed many layers onto paper, manipulating the woodblock by turning it upside down or using only a corner of it.

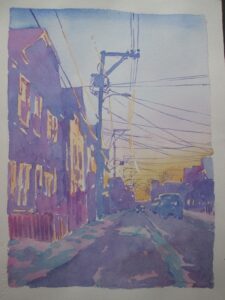

In a small studio on the third floor, she pulls out more woodblock prints, large oil paintings, a picture frame made of dried pasta, and watercolors of Provincetown and Italy, where she visits often. Browne has never felt the need to stick to a certain art form — she allows herself to experiment. “I follow an idea,” she says, “and I see what happens.”

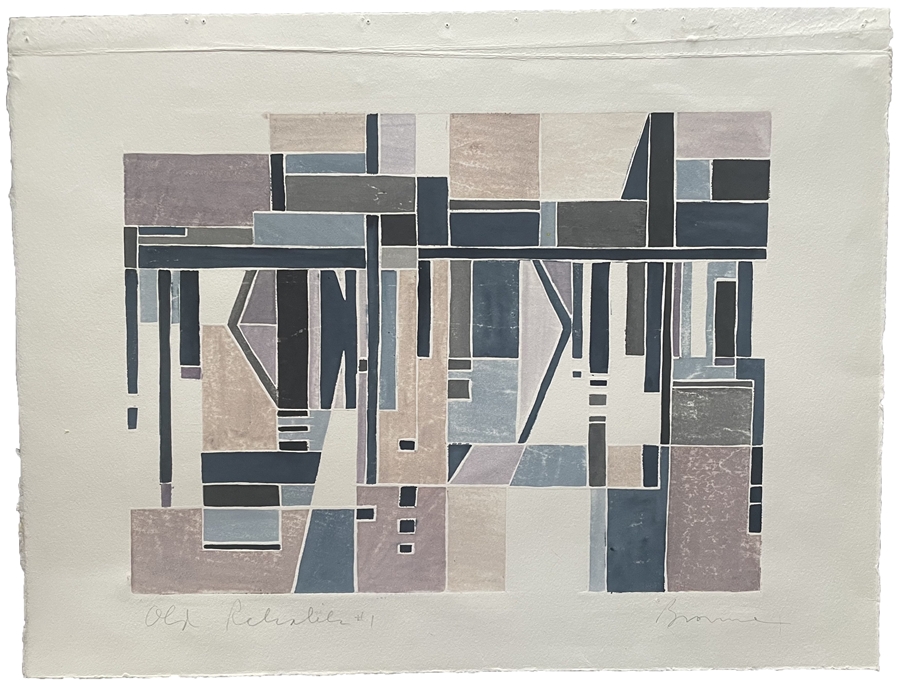

White-line prints — also known as “Provincetown prints” because the technique was pioneered here in the early 20th century — occupy multiple albums. It involves using only one woodblock for the entire work instead of multiple woodblocks for each color. Browne’s pieces at first featured swimmers in the ocean and blooming flowers. Then “I got really tired of that stuff,” she says. She moved into abstractions of fish, houses, and wharfs.

Wharfs inspire her. “I think they’re beautiful forms,” she says, “but they’re rotting away. Since I’ve been here, a couple have disappeared entirely.” She has two images of the Old Reliable wharf behind Marine Specialties. “Every season, there’s less and less of it,” Browne says. One work is painted in walnut ink; the other is an abstract white-line print.

Browne has an idea brewing for a future project — a return to abstract painting, which she was focused on when she first arrived in Provincetown. “I want to do paintings about pure emotions,” she says. She has two three-by-three-foot paintings, oil on canvas, already done. One blooms with chaotic swirls of blue and yellow; the other simmers in shades of pale pink and orange. This abstract series, Browne says, will be her magnum opus.

But for now, Browne is focused on ceramics. Her home studio is where she makes prints and paintings. Her pottery is done in a cooperatively run studio off Route 6. An electric kiln, which Browne manages, occupies a corner of that studio. “I used to have a very primitive kiln,” Browne says. “This one is heaven.”

Terre mêlée dishes in shades of blue line the shelves of the studio. “I fall into something, and I get obsessed,” she says. “Then that’s that. I’m lost in it.” Browne admires a dusky blue plate-in-progress, which is drying before its first firing. “I think it’s really beautiful,” she says. “I mean, look at what it gives you. It’s crazy good.”