After the legendary blizzard of 1978, Nicolas Nobili went with his family to Eastham’s Coast Guard Beach and scavenged for scraps of their summer house, which had been washed away. Among their salvage was a mixed-media assemblage that his father, Conrad Nobili, had made from beach debris. The loosely constructed composition includes a red plastic watering can, glass bottles, and part of a wooden broom — the refuse of a burgeoning consumer culture transitioning from reliance on natural materials to plastic. For Nicolas, who now has the piece in his Eastham home, it’s always been an inspiration.

Before that storm, Nobili spent his childhood in a 1960 modern house his father had built overlooking the beach. It was Conrad’s thesis project at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he studied with Serge Chermayeff, who helped introduce modern architecture to the Outer Cape. The Nobilis stayed in the house during summers and were often there in the shoulder seasons. Nobili remembers leaving Eastham early in the morning so they could get to school in Marshfield, where the family lived the rest of the year.

“It was really formative living in the dunes and having the ocean and marsh as my playground and sources of toys,” says Nobili. “A 55-gallon drum that washed up could amuse us for months.” With his older brother, Conrad, Nobili would make hoops from the roots of beach grass to play with in the wind. Their father taught them to build with hand tools. They collected lightbulbs that had washed ashore from ships and assembled them into sculptures.

Nobili is still fascinated with making things from beach debris. “Coast Guard Beach is where I grew up, so it’s my go-to,” he says. Lately, he’s been finding a lot of lumber, which he uses in large-scale sculptures like Peace, Piece. In it, five blue barrels, one white barrel, and one black barrel are bound with rope to a star-shaped wooden structure. Nobili made it as a response to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and it was exhibited last summer at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

Nobili’s three-acre Eastham property is filled with the stuff he finds: there’s a pile of road signs, buoys hanging from trees (it’s a storage strategy, not a sculpture, he says), and a “masonry section” with clay pipes, likely sewer or water pipes washed away from other people’s beach homes. “All of this is my source material,” says Nobili. “To other people, my wife included, it looks like junk.”

In contrast to the chaotic energy of his property, his works are marked by clean lines and refined shapes. “I love cleanness and simplicity,” says Nobili. In Dearth, he salvaged erosion fencing to build four-by-four-foot pallets that he stacked into an eight-foot tower. Despite its bulk, the sculpture’s uniform lines and the light that filters between the slats create an element of airy refinement.

He used the same sort of fencing to create a trapezoidal sculpture. “I found this fence slumped and squished,” says Nobili. “I liked the funny design.” Instead of straightening it out, he wove rope between the slats and fixed it into a trapezoid. He then attached it to a piece of plywood and framed it so the piece could hang on a wall.

These two works are linked not only by material but also by an insistence on the articulation of a single shape. In doing so, they recall the work of minimalists like Ellsworth Kelly or Richard Serra — or the bold, simple shapes defining the beach house his father built.

In one of his most minimal sculptures, Parlor Game, Nobili attached part of a lobster trap to a distressed piece of plywood. Rope from the trap hangs down like the net of a basketball hoop. The simplicity of the form draws attention to the surface of the plywood: its aged, silvery sheen; the errant scratches marking the surface like lines of a drawing. But the allusion to a basketball hoop moves it in another direction. Here, as in many of Nobili’s sculptures, there’s a playful reference to a familiar object.

In Viking Ship Dream, one of Nobili’s bigger pieces, he arranges wooden slats connected by ropes to suggest a boat. In Snowy Owl, on view at the Cape Cod Museum of Art’s Members’ Juried Exhibition, he uses a white buoy and lobster escape hatch to suggest an owl.

Nobili’s humor is evident in a range of tabletop-size sculptures displayed on his porch (which, along with the surrounding property, functions as his studio). There’s an antique wooden form for darning socks that becomes a turtle, a five-sided slingshot “for people to sit around a table and shoot at each other,” he says, and a board with visual puns that bring to mind René Magritte’s pipe painting and Maurizio Cattelan’s infamous artwork of a banana duct-taped to a wall. The tone of these works is lighthearted and whimsical compared to Nobili’s shape-based, minimalist sculptures.

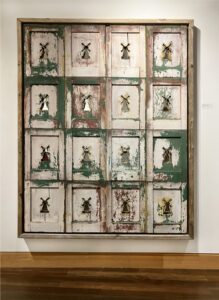

After their beach house was destroyed, Nobili and his family maintained a connection to Eastham. They spent time at the property of Nobili’s maternal grandmother and eventually bought another house. Nobili graduated with a degree in art from Dartmouth College in 1988 and soon afterward returned to Eastham. His grandmother had died by then, and at her home Nobili found a stack of shutters that she had taken down but never gotten around to painting. They had stencils of windmills cut into them, a reference to the nearby Eastham Windmill.

“The backs of the shutters were beautiful because they had three or four different colors of old paint,” says Nobili. He cut them up, arranged them in a grid, and backed each windmill stencil with a mirror, calling the piece Gram Frances’s Shutters.

Soon after, Nobili married Moira Teevens, a fellow Dartmouth graduate, and they returned to New Hampshire, where they both worked at their alma mater. But Eastham called again: in 2005, they moved with their young children to his grandmother’s property. Nobili worked at the Heritage Museum and Gardens in Sandwich and then at Kaleidoscope Imprints, a national supplier of custom apparel in Yarmouth. Now that his children have grown older and more independent, Nobili has again devoted himself to his artwork.

In January, he entered Gram Frances’s Shutters in a juried exhibition at PAAM, where it’s being displayed for the first time. “The piece is about memory,” Nobili says, “like shutters that open and close and provide fleeting glimpses of things.” Like that early piece of his father’s that washed away and then reappeared, the artwork represents Nobili’s interest in place, family, and history and symbolizes the meaning in the ephemeral things we acquire, lose, find, and reimagine.