Stories of Environmental Dread and Horror

Writer and Eastham librarian Corey Farrenkopf says he doesn’t spend much time plotting things out when he writes a story. He prefers to let the direction of the piece surprise him. That way, he says, he can be sure it’ll surprise the reader, too.

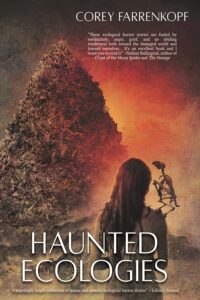

But some ideas are so disturbing that Farrenkopf can’t stop himself from writing about them. Many of his most primal fears are present in his new book, Haunted Ecologies, a collection of 15 short stories he categorizes as “eco-horror”: horror that has its roots in modern environmental concerns.

“A lot of the stories come from my own dread at the way things are changing,” Farrenkopf says. “We’re on Cape Cod, which is affected pretty heavily by environmental changes. There’s a lot in the collection about land usage on Cape Cod and the nightmares that come when it’s managed poorly.”

For Farrenkopf, growing up in Harwich meant having a front-row seat to the realities of environmental change. As a child, he spent a lot of time in the woods behind his house — an environment that has since been bought up, parceled out, and replaced by developments that inspired the “monstrously large buildings” that sometimes appear in his stories.

Farrenkopf says that the modern eco-horror movement likely has its roots in the works of English writer Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951), whose most famous story, “The Willows,” is about two travelers who encounter mysterious forces during an expedition down the Danube River.

“It wouldn’t have been called eco-horror back then, but Blackwood set a lot of his fiction in the woods, dealing with the darkness that comes out of exploration,” Farrenkopf says. “Today, it’s more about people doing unethical things that bring about darkness.”

The stories in Haunted Ecologies range from dark fantasy to cosmic horror. Farrenkopf’s favorite piece in the collection — and the inspiration for its ominous cover — is “The Tap Tap Tap of a Beak,” which tells the tale of an ornithologist who travels to a gigantic mountain of bones to put the remains of an extinct woodpecker to rest.

Farrenkopf will celebrate his book release at the Eastham Public Library (190 Samoset Road) on Tuesday, Feb. 25 at 6 p.m. He will be joined in conversation by John Bonanni, editor of the Cape Cod Poetry Review, to discuss writing, publishing, and setting fiction on Cape Cod. The event is free. See easthamlibrary.org for information. —Parker Mumford

A ‘Traveling Troubadour’ at Preservation Hall

Desmond Curran has stories to tell and music to share. While he can most often be found performing on the street in Plymouth and occasionally Provincetown, he’ll bring his new solo show indoors to Wellfleet Preservation Hall (355 Main St.) on Saturday, Feb. 22 at 2 p.m.

Calling himself the “Traveling Troubadour,” Curran combines original spoken-word poetry with rap and acoustic music. Some of his compositions are original, like a rap he created while working as a dean at a school in Brooklyn; others are musical covers. The show will also include comedy, Shakespeare monologues, and solo scenes from movies including Jaws and On the Waterfront.

Curran, who turns 60 next year, estimates he’s held 25 jobs in fields ranging from commercial fishing to restaurants to special education. Those experiences — along with his early childhood in Alaska, two decades living with his grandmother in Harwich, and time in New York City and Buffalo — inform his stories and poetry. The healing power of nature, especially the ocean, is a theme, too, based in part on circumstances that brought him to Plymouth a year and a half ago to be closer to his family in Orleans.

“I try to put in upbeat and thought-provoking stuff,” Curran says. “If people can either laugh, think about something in their life, or just get out of their own head for an hour and a half and enjoy it, that’s all I hope for.”

Tickets are $20, plus fees, at wellfleetpreservationhall.org —Kathi Scrizzi Driscoll

Singing Together to Build Community

“Singing is good for us,” says playwright Candace Perry. Musician Harriet Korim agrees: “Most people feel like it can have an uplifting and soothing effect,” she says. Perry and Korim, who both live in Wellfleet, recently resurrected the Down-to-the-Wire Choir, which was originally organized in 2017. It meets on the fourth Friday of each month at the Wellfleet Public Library. Their next gathering will be on Friday, Feb. 28, at 4 p.m.

The meetings are not concerts. “We’re not a performing group,” says Perry. Anyone is welcome to participate, regardless of age or ability. “We’re just gathering to sing and to enjoy the music,” she says. The “down-to-the-wire” aspect of the choir has more to do with what’s happening in the wider world than with the group’s impromptu nature. “We’re getting down to the wire with issues like climate change, social justice, and democracy,” Korim says. “It’s that feeling of ‘If not now, when?’ ”

The choir is about building community in troubled times, says Korim. At their first gathering at the end of January, 18 people showed up, some with songbooks, one with a guitar. Before beginning a song, Perry says, “people can teach each other, or we just start singing and see how many people know it.” The group sings well-known protest and freedom movement songs as well as popular oldies.

“We’re not preparing for a performance,” Perry adds. “It’s more for the joy of singing and what it does for your spirits.”

“I love singing with people,” says Korim. “And I’m not into judging vocal ability.” While just listening to music can be good for your mood, she says, “it’s much more powerful if you’re the one creating the vibrations.” See wellfleetlibrary.org for more information. —Eve Samaha

An Artist’s Visual Conversations at Farm Projects

Artist Hanni Woodbury, 94, is “no Sunday painter,” says Robert Shreefter, who, with gallery owner Susie Nielsen, curated “On to the Next Thing,” Woodbury’s current show at Farm Projects (355 Main St., Wellfleet). In fact, he says, Woodbury has never made paintings. Instead, “she has devoted herself to making prints.”

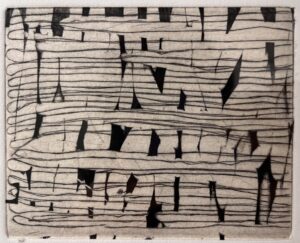

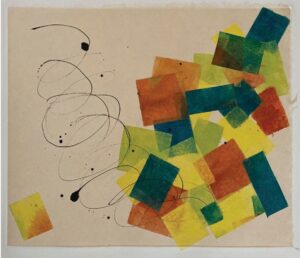

The show is a comprehensive assembly of recent and older prints, a visual landscape of tumbling blocks and searching lines, flushed colors and subdued shadows. The techniques range from monoprint and drypoint etching to aquatint and woodblock printing.

“The older ones are more spare and have less color,” says Shreefter. “More recently, her work is bigger and more colorful.” That trajectory for an artist who has continued experimenting so late in her career is “not an easy thing,” he says. But it makes sense for Woodbury, who works from her studio in South Wellfleet. “Of course she would do that: more or less perfect her techniques, her imagery, and then say ‘No, I want to do something completely different,’ ” says Shreefter.

Woodbury was born in Hamburg, Germany and emigrated to the U.S. with her family just after World War II. Before she started making visual art, Woodbury was a conservatory-trained pianist who later earned a Ph.D. from Yale University in anthropological linguistics. In 2003, after decades of work studying Native American languages, she published the first dictionary of the Onondaga language, which is spoken by the Onondaga First Nation, a Northern Iroquoian tribe.

Woodbury’s visual art is not far removed from her linguistic work. Her art is “all about the ear,” says Shreefter. In curating the show, he and Nielsen arranged the works according to how they imagined they would sound in conversation with each other.

One of Woodbury’s older pieces, titled Musical Notation — which is undated, though Shreefter guesses it’s more than 25 years old — hangs next to Autumn Wind, made in 2022. As its title suggests, the former resembles a musical staff and geometric notation. Autumn Wind is completely different: a jostling, windblown scene, exuberant and bright.

Shreefter says Woodbury has always been straightforward and objective in titling her work. (One piece, in shades of vivid red, is called Shades of Red.) She doesn’t agonize over the meaning of her work, either. “If someone were to ask what it was about,” says Shreefter, “she’d think it was a joke.”

Woodbury will discuss the exhibition in an artist talk on Saturday, Feb. 22, at 3 p.m., and the show is on view until March 10. See farmprojectspace.org for information. —Dorothea Samaha

A Not-So-Final ‘Last Call’

In Tennessee Williams’s 1959 potboiler Sweet Bird of Youth, glamorous fading movie star Alexandra DeLago memorably proclaims, “There’s no more valuable knowledge than knowing the right time to go.” It’s a fitting line to keep in mind for the recent announcement that this fall’s 20th Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival will be the last one.

“We’ve enjoyed our run,” says festival curator David Kaplan in a statement accompanying the announcement. “Productions of over a hundred different plays by Williams from Adam and Eve on a Ferry (2008) to Will Mr. Merriwether Return from Memphis? (2018). From A to W, if not quite A to Z.”

Appropriately, the theme of this year’s festival — which will take place from Sept. 25 through 28 in several venues around Provincetown — is “Last Call.” Along with a production of Sweet Bird of Youth, the schedule will feature a yet-to-be-announced “daring production” of a classic Williams play and a “fresh take” on one of the playwright’s rarely produced late plays, along with a program of short plays by Williams’s contemporary Samuel Beckett.

The festival also announced plans for its annual Tennessee Williams Birthday Bash on Sunday, March 23 at the 1620 Brewhouse in Provincetown, which will include video tributes from past performers including Mink Stole, Penny Arcade, and Yuha Hamasaki along with several international ensembles that have participated in the festival. The annual spring performance gala will follow on Saturday, June 7 at the Harbor Hotel in Provincetown.

Despite the end of the festival’s annual run, Kaplan and his team promise that Tennessee Williams will still have a presence in Provincetown. “The festival will transform after 2025,” he wrote. He added that its mission “will continue in new ways, championing Tennessee Williams in other forms in Provincetown — and around the world.”

A complete schedule of the 2025 festival will be released in the coming weeks. See twptown.org for tickets and season pass information. —John D’Addario

Plays That Spotlight Provincetown Stories

The annual Winter Play Dates series of staged readings at Provincetown Theater will feature three in-development scripts by local playwrights that tell contemporary stories set in Provincetown.

“It will be a very meta experience,” says Artistic Director David Drake. “I think part of pulling the community together is to examine different aspects of our experience out here.”

The series begins on Saturday, Feb. 22, with The Dune Inn by Cody Sullivan. The play is about how the owner of one of Provincetown’s last independently owned guest houses finds it increasingly difficult to resist selling what has become a time capsule of local art and history. The reading will be Sullivan’s first production as the 2025 playwright in residence at the theater, which will provide space and dramaturgical help to create larger works.

On March 20, Joe MacDougall will debut the latest version of A Temporary Land Mass, about a group of Provincetown friends bonded by a 20-year-old traumatic memory who try to untangle its impact. Earlier versions were read at the Provincetown Commons and at a festival of new plays in 2023. “It’s moving, funny, and smart, with different points of view about being an artist and a full-time resident in Provincetown from the ’90s through to now,” says Drake.

Lucy Blood’s Channeling Gene, about a young playwright inspired by local theatrical history who elevates her work during a week-long dune shack residency, follows on March 26. Drake says the play stems from Blood’s own residency. “It’s a sweet play about artistic legacy and how writers and artists feed the newer generation,” he says.

Each reading is presented by local actors and will end with a discussion for audience feedback and support. Admission is free, and reservations are requested. See provincetowntheater.org for information. —Kathi Scrizzi Driscoll