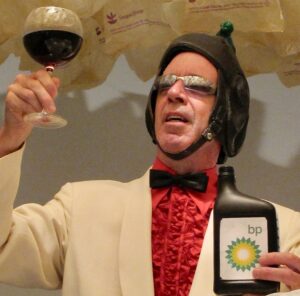

Visitors to Jay Critchley’s Provincetown studio never know what they’ll encounter. In the ground outside his door, there’s a cesspool that he renovated into a whitewashed space complete with a TV and altar. Above ground, there’s the shell of a portable toilet that he uses as a performance space. In the months leading up to his exhibition at the Montserrat College of Art in Beverly, which opens on Jan. 27, oil was the theme.

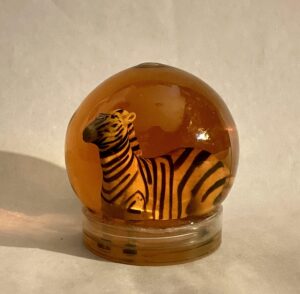

In late November, on a table outside his studio, Critchley was dipping CDs into amber-colored motor oil. Cher, Seal, and Mariah Carey had all been dunked into the rich, viscous material. Inside the studio, he had a table covered in oil-filled snow globes. They appeared as the sentimental, devotional objects of American consumerist culture. In each, the oil enshrined an object from Critchley’s “chest full of toys” in a hallowed glow, but the items themselves were the cheap throwaway products of dollar stores: Eveready batteries, a Waterford crystal angel, a plastic zebra.

Critchley, who grew up in a large Catholic family in Connecticut, has been a fixture in Provincetown since the 1970s. He freely crosses boundaries between art forms, communities, and a range of freewheeling interests. Despite this breadth of activity, the environment has remained a central concern in his visual, conceptual, and performance-based artwork. It’s also central to his activism, which is impossible to disentangle from his artistic practice.

In the 1970s, he organized the Clamshell Alliance in Provincetown, an anti-nuclear coalition. That same decade, he organized Provincetown’s first Earth Day. In Atomic Equinox, a piece from the 1980s, Critchley channeled the ecological and nuclear anxiety of that era in a performance where he covered himself in Vaseline and sand alongside a hybrid American-Russian flag.

Throughout his career, he’s revisited environmental topics in personal projects, such as a gown made from discarded plastic tampon applicators, and annual community-wide events, such as the Swim for Life, which celebrates “the healing waters and ecology of the harbor while raising money for local health services,” according to the event’s website.

The heart of Critchley’s exhibition at Montserrat College of Art, titled “Democracy of the Land, Inc., FLAGrancy,” is a series of American flags embroidered with the logos of oil companies. He produced the flags with other local artists, among them R.C. Patterson, Donna Mahan, and Hilarie Tamar. In addition, there’s a 10-by-15-foot American flag, tarred, feathered, and turned upside down.

“My show is about patriotism and corporatism,” says Critchley. “I’m looking at the history of the Rockefeller dynasty and the democracy of the land.” The work references the extraction and commodification of the land by oil companies and poses questions: “Who owns the land? Who has rights to it?” The questions resound with notions of democracy, Native American sovereignty, and the “rights of nature movement,” which Critchley says is about giving land legal rights.

Critchley gave his collaborators freedom in how they executed the logos on the flags. They are similarly sized so that they don’t obscure the image of the flag, but they’re created with different materials and styles that comically undercut the corporate stiffness. Mahan executed the Gulf logo in rough stitching; a funky braided strip of fabric encircling the word. Tamar used sequins in a painstaking rendition of the Amoco logo, and Patterson’s Chevron logo, with its delicate lines of white stitching, reflects the precise care he brings to his painting and quilt making.

Formally, the corporate logos relate to the flags in their graphic, flat forms and simple color schemes. Here, the flag as a symbol of freedom — or any other American ideal — is hollowed out and gets recast as another corporate symbol.

The act of altering an American flag is not a tepid political gesture, but Patterson took a casual view of his alteration. “I don’t have any problems with it,” he says. “Some people might get upset because you’re desecrating something, but look who’s president.”

Critchley, who often plays with Catholic iconography in his artwork, is not afraid of sacrilege, but this work is less about rebellion and more about challenging the viewer to reconsider what it means to be patriotic. When asked if he considers himself patriotic, he says, “Absolutely! I really want this American experiment to work. The ideals of this country are something we need to keep in mind.”

It’s at corporations, not American ideals, that Critchley directs his ire (although he also implicates colonialism, religion, and consumerism). “Since corporations are running things, especially the fossil fuel companies, let’s put their logos on the flag and call it what it is,” he says. “I started playing with corporations in the early ’80s. Back then, I thought they had too much power and influence. It’s just gotten worse.”

Critchley’s ideas could easily become one-dimensional in the hands of another artist. He skillfully leverages humor — the way other artists might leverage beauty — to make his ideas nuanced, and compelling. His use of a sequined Amoco logo or “no snow globes” is hard to resist, regardless of your politics.

“The seriousness often goes nowhere,” says Critchley. “I’m trying to get underneath the obvious to a subliminal level. Humor is a way to do that.”

Rights of Nature

The event: Jay Critchley: ‘Democracy of the Land, Inc., FLAGrancy’

The time: Jan. 27 to March 5; opening reception: Tuesday, Jan. 28, 6 to 8 p.m.; conversation with Ari Montford: Wednesday, Jan. 29, 11 a.m. to noon.

The place: Montserrat Gallery, 23 Essex St., Beverly

The cost: Free