Helen Miranda Wilson’s studio sits at the center of her Wellfleet house, which was built in the 1850s. The studio seems set up for ideas to unravel and find form: its off-white floorboards have been freshly painted; a skylight and oversized window let in natural light; a lemon tree and basil plant grow in terra-cotta pots on the floor.

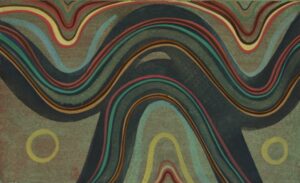

The installation-like mix of references and artwork on the walls of Wilson’s studio provides a look into the way her ideas germinate and develop. At present, the color blue dominates the walls. Two oil-on-panel paintings of simple forms are rendered with thick white lines against blue backgrounds — one robin-egg, the other closer to teal. “The more you leave out of a painting, the more responsibility whatever is in the painting has,” says Wilson.

In Guidon, a flame-like form reaches upward. It’s disarmingly simple and painted with conviction: an attentiveness to the edges of the form, subtly blurred; the confines of the rectangle; and the surface, which has the same soft matte finish as her other oil paintings (she achieves this by painting with no medium). Another image of two downward sloping lines looks familiar, like it could be a corporate logo, but the focus with which it’s rendered elevates it to something that approaches the devotional.

Among these finished paintings are unfinished works; small gouache paintings on paper; sketches; family photographs; an advertisement with a model in a ruffled dress; and the packaging from earphones. Wilson’s criteria for what will go on the wall: “I just want to look at it, so I stick it up.”

Wilson’s creative output is marked by both digression and precision. Before making abstract paintings, she was committed to painting representationally. On the wall is one of these earlier works: an image of a feather. The fuzz of the feather’s aftershaft is rendered with breathtaking detail, like an articulate whisper.

Wilson also painted people. In her foyer is a 1980 painting of two young women putting on clothes from a trunk of costumes: it captures a memory of Wilson with Francesca Woodman, a photographer who became well known after her death at age 22. She was the cousin of Wilson’s late partner, sculptor Timothy Woodman. In a sitting area across from Wilson’s studio hangs her close-up portrait of Christopher Walling, a jewelry designer whom she knew growing up in Wellfleet.

Wilson was raised in the house where she now lives. Wellfleet was a place where she encountered “a whole milieu of people who thought out of the envelope,” she says. “People who made things to look at, to read, or to listen to.” Her father, Edmund Wilson, was a fearsome, famous literary critic, and her mother, Elena Wilson, was an editor who had studied art in Munich and Paris.

Throughout the house, Wilson has sparsely installed paintings and sculptures of other local artists, some historical and others among her contemporaries. There are a pair of Pat de Groot paintings, and on an upstairs mantel are a set of ceramic animal sculptures by Provincetown artist Polly Burnell. By her bedside is a small Louisa Matthíasdóttir painting given to her as a present by Woodman.

Wilson had her first exhibition at Cherry Stone Gallery in Wellfleet in 1971 — it was the gallery’s first show. She lived in New York City for many years afterward and where she exhibited and sold her paintings. “I painted almost every day for 41 years,” says Wilson. “I did it all out of appetite and a certain amount of discipline when organizing for a show. There was no obsession and no grind.”

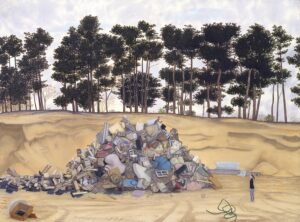

For much of her career, she made landscape paintings, but even in this format she was digressive, ranging widely in her subjects. In Wellfleet, where she spent summers until moving here for good in 1999, Wilson painted the town’s transfer station, its night skies, and bare trees in fall. In New York, she painted industrial sites and views from the top of the World Trade Center.

“I painted landscapes from direct observation wherever I found myself,” says Wilson. “I never used photos. Painting outdoors is all about surrender and being completely there, in the moment. You can’t control it.” She never took shortcuts in her landscape paintings. Her finely attuned attention, concern with detail, and holistic vision reveal a posture of full surrender to her subjects.

When Wilson returned to live in Wellfleet, she became involved in town government, where she served on several committees including the select board. The experience drove Wilson toward abstraction in her studio.

“The town stuff was so much reality,” says Wilson. “I stopped wanting to work from life.”

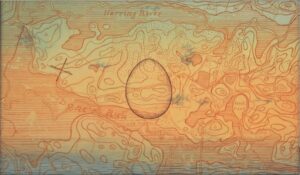

A few of her early abstract pictures hang in her studio, including a grid of tiny colored squares and a gouache painting of undulating lines in shades of earthy green. An agenda from a Herring River Restoration Committee meeting is also tacked to her studio wall. In the margins of the photocopy, she created thumbnail sketches of organic, pod-like forms.

Some of her more recent abstractions have associations with reality, like a series composed of long lines on yellow grounds that she relates to telegrams. There’s a bluejay’s feather and some accompanying works on paper that lift their colors and lines from it. Despite her variation, a sensibility ties the work together — it has something to do with the diminutive scale, her confidence, and her meticulous touch.

“I want to make more of those yellow paintings,” says Wilson, gesturing toward the telegram pictures. “But I don’t get to it. The way my life is now, there aren’t enough hours in the day.” Despite all the generative energy in Wilson’s studio, she isn’t painting much these days, and most of the work on display was done before 2018, the year Woodman died.

“I felt lost after Tim’s death,” says Wilson. “That same year, I developed cataracts to the point where I couldn’t draw or paint. I haven’t gone back to the studio in a regular way since then.”

Wilson and Woodman had been together since they met at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1970. A painting of Duck Pond in the entranceway of the house is one of Wilson’s earliest — it commemorates a conversation the two had there, agreeing to an equal partnership.

Wilson isn’t sure when she’ll pick up an active studio practice again. Her paintings were never done with pretense or artifice. Despite successes, she never stuck with a particular subject if she wasn’t feeling compelled. She likens her current absence from the studio to a lack of appetite, not a creative block — and she’s fine with it. “I’ve learned not to hate myself for the stuff I’m not able to do any more,” she says.

And yet, the studio isn’t packed away. Some paintings in the space remain partially completed. Like unfinished sentences, they bristle with suggestion, their resolutions uncertain. Thinking about her future, Wilson recalls a line of Grace Paley’s poetry about “the open destiny of life,” which hangs in her kitchen.

“I’m moving forward,” says Wilson, “but I’m not sure where I’m going.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on Jan. 9, incorrectly reported that Elena Wilson, Helen’s mother, had studied art in Provincetown. She studied in Europe with Provincetown artist and teacher Hans Hofmann.