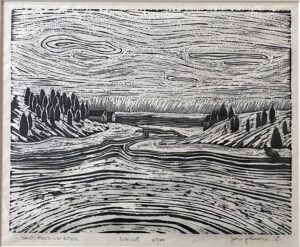

In a sunny room of her Orleans house, Naomi Rush begins a tour of her art collection with a black-and-white linocut by Joyce Johnson titled Salt Pond — Winter. Rush’s partner, Fred Boak, bought the piece before they met, and it anticipated their connection. Johnson, the founder of the Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill, was an important role model for Rush when she was taking pottery classes there as a child.

Rush’s family moved a lot, but she says the most constant home she had was a house in Wellfleet that her parents bought in the late 1960s. In May 2023, Boak and Rush moved into the Orleans house. “We’re creating a home for ourselves,” says Rush.

Filling it with art is one way they’re doing that. Artworks line every wall, are propped up on every shelf, and sit on tables and floors in thoughtfully arranged tableaus. Their collection includes sculptures, prints, paintings, collages, carvings, and photographs.

Boak and Rush — they call each other their “sweethearts” — have been together for 10 years. Boak, who grew up in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., sings with the Chandler Travis Philharmonic. Rush attended his shows, and they would smile at each other until they finally went on a date.

“We’re a late romance,” says Rush. “We’ve learned about each other by looking at art together.”

Boak has a radio show, Omnipop Omnibus, on WOMR every other Sunday afternoon. Rush would walk around Provincetown listening to Boak’s program in her earbuds and looking at art on Commercial Street. “When I got out,” says Boak, “she’d come and tell me, ‘You have to see this.’ ”

Most of the pieces in their collection were Christmas gifts to each other. Their gift-giving tradition works like this: when either buys a piece during the year, it’s set aside on the giver’s own closet shelf, not to be seen again until Christmas or a birthday. When that gift-giving day comes, “There’s the present stash,” says Rush.

Sometimes one will buy a piece and give it to the other to put on their shelf. Forgetting is key — Boak once fell in love with a photograph in a Wellfleet gallery and bought it. Rush put it on her shelf, and it slipped Boak’s mind. On Christmas, he opened it. “I fell in love with it all over again,” he says.

Rush doesn’t think of herself as a collector. She and Boak are patrons of the arts; their collection is the inevitable result of placing value on the efforts of artists. When they buy something, says Rush, “It’s a vote of confidence.” Most of the artists they’ve supported have been young or not widely known.

They’ve learned each other’s tastes. “We complement each other,” says Boak. “Naomi sees the details, all the pen strokes. I respond very viscerally to things. I’ll see a piece and say, ‘That’s the one.’ ”

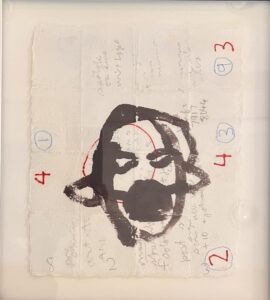

A small piece titled WD 8243 by MP Landis, who shows at Farm Projects in Wellfleet and Bad Habit in Provincetown, leans against the brick fireplace. “It’s not everyone’s cup of tea,” Rush admits. The rough black outline of a face appears suppressed, rageful. The paper is creased and worn from time spent folded in a pocket. Lists and scribbled notes in pencil and numbers in thick red ink hover around the face. The face is like a disgruntled character in a bustling city among the other artworks leaning against the fireplace.

There’s a sculpture, Into It #3, made from found wood by Mike Wright, who shows at Alden Gallery. It’s based on a 1927 painting by Blanche Lazzell, Painting VII. The sculpture commands the corner like a geometric portal. Two pieces, a painting, Eclogue by Jeannie Motherwell, and a sculpture, Catch by Damien Hoar de Galvan, occupy a nearby windowsill. Rush and Boak got both at Schoolhouse Gallery.

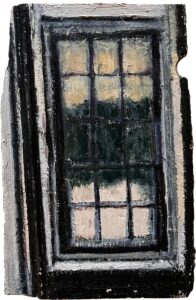

There’s a rough piece of wood painted like a fragile window on the dining room table. Called Sash, it’s part of a series of paintings by Megan Hinton on scrap wood from the renovation of her Truro house.

Rush and Boak are considering installing a cork wall in the living room, to which they’ll attach unframed artwork. One unframed piece rests on the coffee table: a manipulated polaroid picture by Jon Verney. Rush and Boak bought it at Farm Projects, where Boak says Susie Nielsen, the owner, has created an inspiring community of artists.

On the mantle is a large, breezy triptych called Mussel and Seaweed Triptych by Helen Grimm, who shows at Four Eleven Gallery in Provincetown. “It’s one of the first things we brought into the house,” says Rush. She lays another on the table: a photograph by Jamie Casertano. “This is the Mary Heaton Vorse house on the day of the estate sale,” she says. “Can you believe it?” She says she bought it without knowing its importance. There are ghostly white shapes left behind after the paintings were taken from the wall and frame wires etched in the soot, too. “It’s inherently magical,” says Rush. “It’s some kind of sacred object.”

Rush cradles another sacred object in her arms: a carved wooden totem made by Joyce Johnson. “You can see the marks of her hand,” says Rush. “You get a sense of her ambition and her simplicity and her persistent drive to make things.” Rush, an artist herself, likes to draw and make collages based on the piece.

Amid the figures, painted and sculpted, dancing and scowling, a bronze bust in one corner seems to resemble Rush. “That’s me as a little girl,” she says. The piece is by Wellfleet sculptor Penelope Jencks. One summer, when Rush was 11 or 12, she sat every afternoon for Jencks, who would nurse her baby while she worked.

Their collection doesn’t just have aesthetic meaning, says Rush. She and Boak aren’t necessarily investing, either. “There’s a romantic side to it,” she says. “The purpose is the connection between us, the growth in our own aesthetic understandings, and the building of community.”