“Pick a chair,” says poet Keith Althaus, welcoming me to his house on Shore Road in North Truro. He and his wife, Susan Baker, have lived in the house since 1984. The space is full of Baker’s humorous paintings and sculptures, which she also displays in a gallery — the Susan Baker Memorial Museum — at the front of the building.

Before I sit down, Althaus decides that if he’s the one being interviewed then the reporter should sit behind the yellow desk and he should sit in front of the desk, as if applying for a job. The yellow desk is covered with books and old photographs.

Althaus’s wispy blond and silver hair falls around his head. His deep-blue eyes are alive behind his rectangular glasses. He’s gesticulating — composing his answers with a black pen in his right hand like he’s in front of an orchestra. He describes his arrival in Provincetown on Nov. 1, 1969.

“On that day, I met most of the people who were important to me for the next 40 years,” he says. Althaus was part of the first writing cohort at the Fine Arts Work Center along with six other poets and writers, including Roger Skillings, Louise Glück, and Bill Gilson.

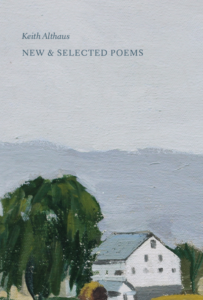

Althaus’s lyrical poems are tied to life at the end of the Cape, where he has remained for more than a half century. He opens his latest book, New & Selected Poems, published this year by Grid Books, and softly reads his poem “Late Bus, Provincetown.”

In the poem, Althaus responds to the large-scale photographs by Norma Holt of Portuguese women — fishermen’s wives — installed on the outermost building at the Provincetown Marina: “They do not look, but stare/ at everything: the breakwater/ floats, gulls, the fleet/ coming in, trailing clouds/ of bird life, raucous,/ joyous as a sudden whirlwind of litter/ on a corner in the city.”

Althaus worked at a tree nursery in York, Pa. before coming to the Cape. “It was also a pig farm,” he says. “I have a poem called ‘Self-Portrait in Pig Shit,’ ” he adds. He hands me a white folder with the original ad he saw in the New York Times for the FAWC residency in 1968 — his ticket out of the pig farm.

Althaus remembers the layout of buildings at FAWC in the late 1960s, who was sleeping on couches, and how Anne Sexton was going to come and give a talk but then killed herself.

Stanley Kunitz, a co-founder of FAWC, would invite writers and artists in his circle like Alice Neel and Robert Bly to come to Provincetown to talk about their work. The visiting artists and writers didn’t get paid, but they’d get a free room at Monroe Moore’s place.

Since those early years at the Work Center, Althaus, 79, has won a Pushcart Prize, a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, and a grant from the Mass. Council for the Arts.

He is wearing a black Bagel Hound hoodie that says “Death by Bagel,” illustrated by Baker. Bagel Hound, with shops in Wellfleet and Provincetown, is owned by his son, Ellery, who, Althaus reminds me, once biked across Siberia. “For Ellery,” included in New & Selected Poems, illuminates spiritual questions between father and son during their walk home from the post office. The poem was originally published in Althaus’s 1993 book, Rival Heavens.

In his new poems, Althaus has continued writing in short lines that flow swiftly down a page. He says that “excess stuff” is no good. A spiritual vein runs through the work. In “Leaving the Party,” the speaker is surrounded by a “golden haze of perfume and smoke” and listens to gossip and conversations about careers. He drifts into the corner of the room to contemplate original sin and the “place of pain in the universe.”

Althaus often writes in his chair amid Baker’s sculptures and paintings. “The best is when you have four or five poems going at once,” he says. “At least two — so you can fall back on another one.”

The technique he’s used for decades is somewhat simple: one big black notebook. “Now they seem to be on sale — they’re like five dollars, but they used to be 10 dollars,” he says. “The secret of writing is you put everything in the same book. If you make a revision, you put it all right there. Always in the same spot. The moment I need something I can go right to that location in the book,” he adds. Althaus fills up one of the books every nine months.

After editing his poems in the black notebook, he types them out, prints them, and places them in a white binder where “they’re harder to get at,” he says. “A poem is never finished, only abandoned,” says Althaus, quoting Paul Valéry.

Althaus considers what it means to write a great line and where a great line comes from — a question no one can truly answer. Like a painter starting with an empty canvas, the poet has a blank page.

He refers to “The Thought Fox,” a poem by Ted Hughes about a fox entering the snowy field of an empty page. “Suddenly the thought fox has been through it, and there’s the poem,” says Althaus. “It’s gone before you can take credit. You can say, ‘I thought of that,’ but it’s on the page before you get it. You couldn’t do it again if you wanted to.”