The wharf in all its stages — from bustling workplace to burnt timbers — has seen generations of artists setting up easels to capture the arrival and departure of schooners and trawlers, the loading and unloading of barrels and crates, and the gradual decay of most of the more than 50 wharves that lined Provincetown Harbor before the Portland Gale of 1898. It’s also where two of Provincetown’s most important communities, artists and fishermen, have long intersected. For both, the wharf became a place of departure for risky ventures, whether physical or creative.

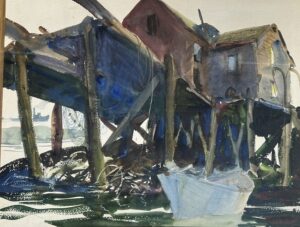

“Risk” is one of the first words that comes to Arthur Egeli’s mind when he looks at John Whorf’s watercolor of Cannery Wharf, prominently displayed in his Commercial Street gallery. Egeli believes that Whorf, a realist painter, made the image in the late 1920s, when the artist was in his mid-20s. Whorf had studied for six summers with Charles Hawthorne, the founder of the Cape Cod School of Art.

Egeli notes that the use of light in Provincetown Wharf is inverted from what’s found in a typical impressionist-era landscape. “It’s all dark and defined by the light coming through the breaks in the wharf,” he says. “It could only have been done from an extreme perspective, looking up at the monster wharf.”

Cannery Wharf, now the site of the new East End Waterfront Park, was a favorite among artists with its offset pier sheds jutting into the harbor. The wharf was used primarily for canning, but in November 1926 a violent storm loosened a Coast Guard cutter from its mooring and tossed it against the wharf. Whorf captured the resulting destruction in his image of the sheds isolated in the harbor, teetering on pilings angled in all directions.

“Imagine behind him Hawthorne’s class is painting a pretty young girl on the beach,” says Egeli, “and Whorf is getting bored with that, looks behind him, and sees that kind of ashcan motif.”

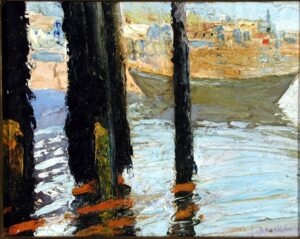

Gerrit Beneker painted Under a Wharf in 1914, more than a decade before Whorf’s painting. Though Beneker uses a different medium, he also focuses on a wharf’s underside. In his diminutive oil painting, measuring just 8 by 10 inches, the wharf’s dark pilings are offset by pale blue water that seems to ripple in the light. A dory lolls against the background view of a sand-colored village, completing an image reminiscent of impressionist scenes of the European coast.

“Beneker was one of the founding members of the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, and this was one of the artworks that started the permanent collection,” says Christine McCarthy, PAAM’s CEO. The painting was on loan to the town and was displayed in Provincetown Town Hall when it was stolen in 1981 and recovered from a Tucson gallery 15 years later. (The identity of the thief and details of how the painting got to Arizona remain mysteries.)

“Beneker was mostly known as an illustrator, but this painting demonstrates his ability to produce a small but powerful composition that very much speaks to the Hawthorne school,” says McCarthy. In their paintings, both Beneker and Whorf reveal the influence of Hawthorne, who encouraged students to work from life to capture color and luminosity.

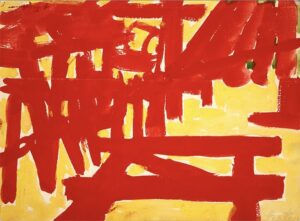

In the modern era, with only a few of the original wharfs remaining, many artists have been drawn to the pilings that stand like weary sentries in the harbor. Lester Johnson’s 1955 Red Pier was one of a series of watercolors completed during the decade he spent in Provincetown, well before he became known as a figurative expressionist. Johnson studied with Provincetown’s other famous teacher, Hans Hofmann, who, unlike Hawthorne, emphasized abstraction. In Red Pier, pilings become abstracted linear marks.

“The piers … are depicted with a primal, gestural line that came to define his later figures,” according to exhibition notes from a 2015 show at ACME Fine Arts in Boston.

Four decades later, Rose Basile similarly used thick slashes of bright paint to sound an artistic fire alarm in Oh My God! We Caught the Last Cod! Her 1996 oil on canvas depicts two faceless fishermen on a wharf, one raising his hands above his head as if surrendering to the loss of his livelihood. The “last cod” lies lifeless in an open coffin at his feet.

A fisherman, gardener, and educator, Basile began to paint seriously in her 60s. The economic hardships endured by fishermen and their families were a frequent focus of Basile’s work, which was featured in exhibitions at Provincetown galleries, PAAM, and the White House.

“Rose was a force,” says McCarthy. “Her art was an outlet for what was happening in the world and on Cape Cod — using bold color choices and a variety of media helped convey her passion.”

For artist Dianne Longchamps of Wellfleet, a self-described “wonky” abstract impressionist, the lure of the wharves is purely artistic, untethered to local history or hardship.

“When you look at an old wharf or pilings or pier, there are no straight lines,” she says. “They’re all slanted and crooked and it’s not perfect. That’s what I like to paint.”

She uses a palette knife to blur lines and experiment with rich color. Her painting of Captain Jack’s Wharf in Provincetown features a vibrant mix of pinks and purples, acidic yellows, and teal.

For Longchamps, whose paintings were featured in a recent exhibition at the Wellfleet Public Library, the wharves’ decay isn’t to be mourned so much as honored.

“The way they are now — it’s like watching a person get older,” she says. “You see the crevices and cracks, but that’s the beauty of it. I think these wharves have aged beautifully.”