Perception is an abiding interest for artist Sonita Singwi. “How do we see things and engage with the world around us?” she asked during a gallery talk at Farm Projects in Wellfleet on Nov. 9, where she was in conversation with Ezra Shales, an art history professor at Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

Singwi includes shadows, objects glimpsed in passing, and accidental blurry photographs as her sources of inspiration — moments when one’s powers of perception are stretched and conclusions are evasive.

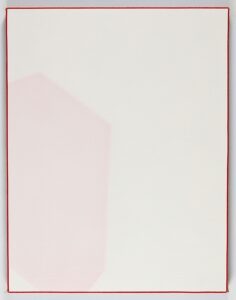

In her painting Untitled 5, Singwi plays with this ambiguity. A pink shape hovers on the left side of the canvas. Its presence is subtle; it’s just slightly darker than the white background, and its soft edges are blurred. Then there are the edges of the canvas, lined with thin, fluorescent strips of tape. Is this where our attention should land? What is this aberration?

In a statement accompanying her current exhibition at the Wellfleet gallery, Singwi relates her focus on ambiguity to the concept of “maya” in Indian philosophy: the idea that the physical world is an illusion. Singwi, whose father is from India and whose mother is from Germany, is a first-generation American living and working in Brooklyn. She has visited Wellfleet in the summer for the past 13 years, renting a house on Lieutenant Island once owned by the sculptor Gilbert Franklin.

Singwi’s exhibition, called “Break,” includes paintings done on linen and tabletop ceramic sculptures — abstract pieces, Shales implied, starting the conversation this way: “I find abstraction soothingly complex.”

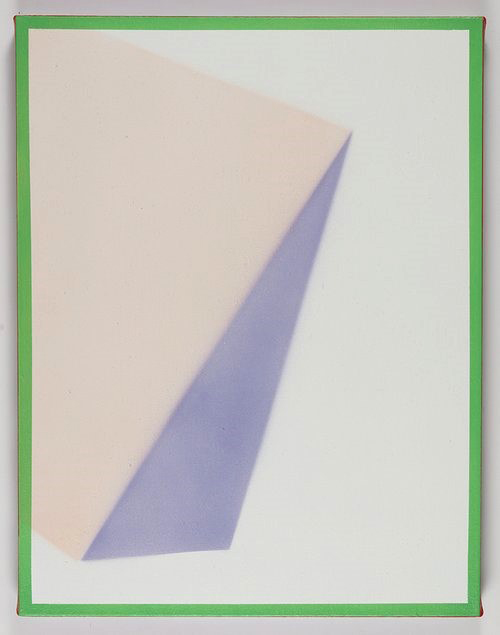

A case in point: Singwi’s painting Fold. Its shades of beige don’t clamor for your attention. Geometric shapes fan out cleanly from the painting’s center, smartly contained in the rectangular frame. There’s no heavy content here, but the longer you stay with the image, the more confounding it becomes. Is this painting an abstraction of a conch shell? Or an image of folded paper, like origami? Are the shades of beige conveying light and shadow? Is the painting actually about negative space — the raw canvas? Is this even an abstract painting? Soon the questions become more compelling than the answers.

Singwi pushed back against Shales’s emphasis on abstraction. “Abstraction is a strange term,” she said. “I see it more as a continuum. It connects with the way I see the world.”

In her earlier work, she said, she got ideas from images of interior views of bodies and mollusks. Her current exhibition, despite its proximity to the austere tradition of geometric abstraction, also has roots in reality, specifically pop-up books, in which flat surfaces are scored and folded to create three-dimensional elements.

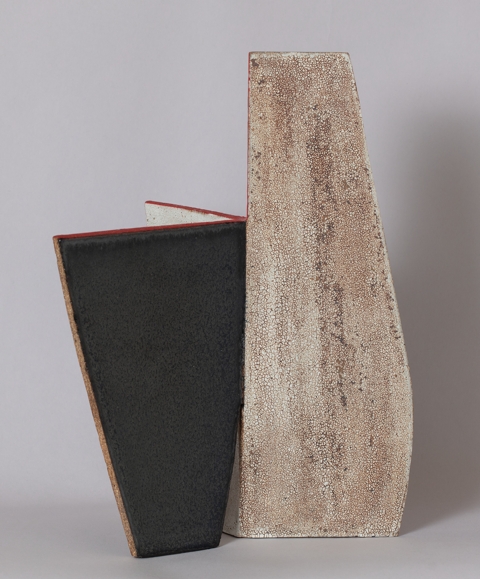

In her sculptures, Singwi uses thin ceramic slabs arranged in various configurations to suggest the flat planes of paper. The reference to pop-up books is clear, but the tactile quality of these glazed and cracked surfaces takes the work in a different direction — perhaps back to abstraction and its insistence on materiality.

“I am interested in the materiality of our everyday life,” said Singwi. This interest shows up in the surfaces of her paintings, too. Her shapes might be sharp, but her surfaces aren’t slick. She draws attention to the linen texture of each painting and the way it imperfectly absorbs paint.

Singwi earned a master’s degree in art history before receiving an M.F.A. from Hunter College, but she draws just as readily from life as she does from art theory and history. Ellsworth Kelly, Hannah Wilke, and Fred Sandback pepper the discussion of her art, but her grandfather also shows up.

“The paintings have a personal history,” says Singwi. “My grandfather folded everything. We were always very careful about how we folded our handkerchiefs or serviette when we ate at the dinner table.”

Singwi’s paintings surrounded the crowd at the gallery talk, but it was the back-and-forth dialogue that seemed to reveal their meaning — or their mystery. It was a group effort in perception.

“I love the blurred pieces,” said gallery owner Susie Nielsen, referring to a few of the paintings that feature barely perceptible shapes. “I feel like I can’t get to it, and I find that very interesting.”

Painter and photographer Stephen Aiken spoke of the “thingness” of the paintings. He was working in 1970s New York when minimalism and conceptualism were gaining traction in the art world, and he saw here a reminder of Robert Ryman’s white-on-white paintings.

Megan Hinton, another painter in the audience, was curious about the edges. “A majority of the marks are on the edge of the painting, and then there’s this primary form,” she said. “Are you intentionally trying to direct us to the edge of the painting?”

“Yes,” Singwi replied.

“That’s interesting,” said Hinton. “If you go into a museum, you know someone is a painter if they’re looking at the edge of the painting. You’re making this statement about how a painting is made — or not made — by directing us to its edge.”

Nielsen connected Hinton’s comment to Untitled 5. “For me, that painting is all about the pink part,” she said, “but I probably wouldn’t have been as entranced with the pink shape without the edges jarring me.”

Joerg Dressler — yet another painter in the audience — was curious about the placement of the shapes on the canvas, which all lean at various angles. “They walk a fine line between being a mistake and being intentional,” he said. “In these slight tilts, are you playing with a desire for someone to set it straight?”

“Yes, I’m probably the person who would want to set it straight,” said Singwi, laughing. But, she added, “It’s more interesting if it’s off balance — but not dramatically off balance.” Her comment doesn’t quite give clarity, but it fits the spirit of her paintings, which never fully offer an objective answer.