At six foot six, sculptor Cole Cook’s head almost touches the ceiling of his garage studio in Truro. Two black lead pencils poke out of the chest pocket of his Army-green apron, powdered with wood dust. Standing in front of a neatly labeled teal file cabinet, he says, “There’s a centimeter of water on the sand flats, and I want my work to get to the experience of witnessing that.”

Cook’s process for his tidal sculptures, or “sand patterns,” as he calls them, begins with photos taken from his adventures in nature — searching the coastline and standing under trees. In his recent work, he found himself fascinated by patterns in the sand observed at low tide.

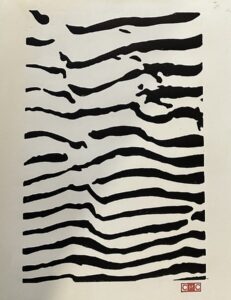

“The shapes the waves make as they recede from oceanside beaches look like veins,” says Cook. In his exhibition at Zone 7a in Provincetown, opening this week, he is showing works that translate this natural phenomenon into sculptural forms using different types of wood: red and white cedar, walnut, and maple.

Cook, 36, started making art during the pandemic. After 18 months of California lockdown, he decided to leave L.A. with his two cats and head for the natural landscapes of Truro. He’d been coming to the Cape since he was a baby. Cook says the Outer Cape is a place of safety, reflection, and inspiration for him. It’s also where his art practice has deepened. He sculpts outside, and when the weather turns bad, he goes inside for a few months and makes prints on his press, some of which he showed last February at the Truro Community Center.

Cook grew up in L.A., where he developed into a serious baseball player. By his sophomore year at Palisades Charter High School, he was throwing 90-mph fastballs, which put him on a trajectory toward professional ball. He was drafted by the Seattle Mariners in his senior year but opted to attend Pepperdine University, where he was an All-American athlete, majored in creative writing, and minored in film. In 2010, the Cleveland Indians (now the Cleveland Guardians) drafted him, and he played on their minor-league affiliate teams until 2015. He’s still involved in the game as a volunteer assistant coach for the Orleans Firebirds of the Cape Cod Baseball League.

As a coach, Cook would tell his players, “No one needs to sit here and deal with what we do when we’re excellent. We’re here to figure out what we do when we’re not.” He followed his own advice when approaching artmaking. He took a course at a community college but found he could better chart his own development as a self-taught artist using online tutorials and other forms of rogue apprenticeship. Cook has used what he learned from being a professional baseball player — a sense of the dedication, time, and craft needed to accomplish a goal.

Cook wakes up early, sits with his cats, and writes in his journal for an hour before he enters his workshop. “I have the space, and I will make myself show up every day,” he says. He is frank about his work: “I make what I want to see,” he says, standing in front of neat stacks of kindling.

After taking photographs in the landscape, Cook begins his sand pattern sculptures by illustrating his reference photographs on a computer. From there he projects the drawings onto pieces of wood. Mark-making provides a map for the hours he will spends using a Dremel or die grinder to carve the wood.

It took Cook some time to figure out how to take the sketch, move it into a drawing, and then move the drawing into a sculpture. “The ridges of the lines are following the high point, topographically, of the shape,” he says.

After the piece is carved, Cook may sand for up to 15 hours before using tung oil for a shiny, polished finish. He works with abrasive sanding cones that look like little wheels that go on a drill bit.

“There’s no one way to do it,” he says. “The sanding is to create a uniform pitch.” He sometimes takes a piece of Scotch-Brite, wraps it in sandpaper, and sands for hours. “If you do it for an hour, you might not see a change, but you did something,” he says. He finds lessons in hours of work that sometimes produce no results.

Cook’s new low-tide sculptures fulfill an ambition conceived when he first moved to the Outer Cape and looked at the rolling patterns in the sand.

“I thought, if I ever get good enough, that’s what I’ll make,” he says. His sculptures praise the natural rhythms he’s devoted much time to observing. Their undulating forms embody the meditative quality of repetitive lines in the sand. “These patterns happen twice a day,” he says. “They’re abiding. I’m a sensuous creature. There will be a sign at Zone 7a that says touch the wood, touch it, it wants to play with you.”

Cook walks over to an almost finished piece made of walnut. “It’s a little like a lover,” he says, before noticing a mole that he wants to smooth out and rub down with sandpaper.