A sculpture by Conrad Malicoat adorns the grave of Dr. Clara Thompson in the Provincetown Cemetery. It’s not a likeness of the woman it honors, but it’s figure-like, tall, sensuous, and strong, carved in granite, balancing on one end of its stone plinth like a person leaning into the wind. Or does it seem to billow? Perhaps the whole thing is a column of smoke or an ink blot come alive.

Clara Thompson, who was born in 1893 and died in 1958, was one of the leading psychoanalysts of her time and a cofounder of the William Alanson White Institute in New York City. She was also a close friend of Malicoat’s father, the painter Philip Malicoat.

Conrad, who died 10 years ago, was born in Provincetown in 1936, attended Provincetown High School, and graduated from Oberlin College in 1957. The son of artists — his mother, Barbara Malicoat, was a printmaker, graphic artist, and craftsperson — Conrad followed that creative path, too. He was a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center from 1968 to 1970. But unlike his parents, Conrad tended toward the three-dimensional in his art.

Malicoat mostly worked in wood, metal, and stone. Four of his sculptures are in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. In Provincetown, his best-known works are the exuberant jumbled brick chimneys and fireplaces that several homes and at least two restaurants boast — the Red Inn has one and so does the now closed Napi’s. But what fewer people know are the pieces that adorn graves in the town cemetery. Besides Clara Thompson’s, there are three others.

Robena Malicoat, Conrad’s eldest daughter, recounts the beginning of her father’s gravestone sculpture work. A few months after her birth in 1961, he built a camper on the back of an old truck. Then he and Robena’s mother, Anne Lord, took their firstborn and hit the road. “They wanted to go find the magic place where they were going to settle down and do their art,” Robena says.

They spent the winter in Llano, Texas, where Malicoat befriended the owner of a local tombstone-carving company and was offered part of a stone-carving studio to work in. He sculpted granite, which was quarried there.

“Conrad would find quarries in different parts of the country,” says Robena. That’s why some of the stone he used is pink and some of it is gray.

In Texas, says Robena, “most of the stone-carvers were Mexican. They didn’t have great English, and they could not figure out what the heck Conrad was doing.” His work made no sense to them, she says. “They thought it was hilarious. And Conrad thought it was hilarious right back.”

Eventually the family returned to Provincetown. Outside Malicoat’s workshop, says Robena, there was a big air compressor that would kick on when he was working. “I always loved the sound of it, because I knew he was in his studio and he was happy,” she says. “He had a good time in there with that stone.”

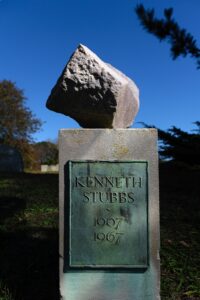

A second Malicoat sculpture is the gravestone of the artist Kenneth Stubbs, who died in 1967. This piece brings to mind a thick limb, fallen perhaps, but still perfectly balanced.

Another Malicoat sculpture stands atop the graves of the artist Irving J. Marantz, who died in 1972, and his wife, the teacher Evelyn M. (Hurwitz) Marantz, who died in 1975.

Nearby, a fourth Malicoat piece marks the grave of the artist Robert Motherwell, who died in 1991. The bronze plaque, green with age, was set by Malicoat on an irregular boulder. It is perfectly earthly, yet compared to any upright, smooth marble slab, it is perhaps the ultimate abstract work.