A conversation with a friend pushed Karma Kitaj to consider the narrative quality of her own artwork. “Why do you paint what you paint?” her friend had asked. It was a question that stuck with her, so she brought it to the attention of the Outer Cape Art Collective.

Once a month, members of OCAC gather on Zoom to discuss their work. This month, Kitaj led the dialogue involving 20 other artists from her home studio in Bernardston, in the northwestern part of the state.

“I started painting 15 years ago and I never thought about the meaning of my paintings,” she said. “I just painted intuitively.” But her friend’s question, along with Anne West’s book, Mapping the Intelligence of Artistic Work, Kitaj said, inspired her to explore the ideas behind the making.

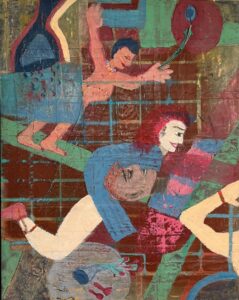

Through a series of slides, Kitaj showed the group works by Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, by Kathia St. Hilaire, whose work she had seen at the Clark Art Institute, and by Jacob Lawrence, whose paintings she had admired in an exhibition about the Harlem Renaissance as a way of exploring the presence of narrative. She also showed some of her own figurative paintings where she integrated topical issues like the male gaze and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Like many others in the group, Kitaj devoted herself to art later in life after a career in another field. She had a private practice as a psychotherapist. When her brother R.B. Kitaj, an internationally known painter, died in 2007, his son sent her some of the late artist’s brushes. Soon after she got them, she started painting. “He had innate talent as a youngster,” said Kitaj of her brother. “He got a lot of attention in my family. I was the little sister.”

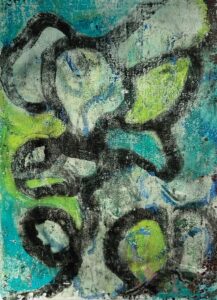

In her pursuit of her “encore career,” Kitaj took a variety of art classes, including encaustic courses at Castle Hill in Truro and, during the pandemic, online classes with Laura Shabott, a Provincetown artist, and Alana Barrett, an artist in Miami. That course, called PROMPT, gained a devoted following of artists connected to the Outer Cape who, like Kitaj, were coming to art as a second act.

“Older people going into art are often invisible,” said Shabott. They were not invisible to her, and she “taught them as if they were in art school.”

After Shabott and Barrett stopped teaching their course in 2023, a number of those involved in PROMPT formed the collective. It retained some of the DNA of Shabott and Barrett’s course, including an experimental approach to painting and a structure that includes group critiques, discussion of historical and contemporary artwork, and prompts to help generate new work. “I’m taught by everyone,” said Kitaj.

Her slide show ended with prompts asking participants to articulate values and assess whether their artwork exposes or comments on stereotypes. The conversation that followed was wide-ranging, honest, and thoughtful. There was some pushback to Kitaj’s emphasis on content.

“I don’t come at my art with a lot of elaborate intention or a need to create any kind of objective or philosophical meaning,” said John Koch, who was an arts critic and editor at the Boston Globe before being “reborn in 2005 as an artist.” He said his process was much more intuitive than that. Anne Doolittle had similar reservations about meaning: “I resist the urge to say what a work is about before I make it.”

From there, the conversation widened. Doolittle, a writer and poet, brought up the early 20th-century New Criticism literary theory movement, which argued that everything one knows about a work should come from the work itself.

Kathryn Stearns went farther back in history, discussing how narratives in the past were typically cultural rather than personal. She discussed her experience working as a docent at the Hood Museum of Art in Hanover, N.H. “So much of contemporary art is narrative, but it’s hard for viewers to divine the meaning without reading labels,” she said, which generated further discussion about whether or not it’s important to understand an artist’s intention.

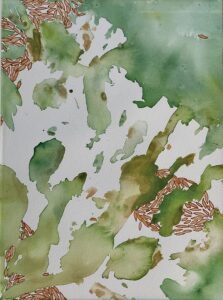

Some saw connections between the question Kitaj had raised and what was happening in their studios. “I started a series of bombed-out buildings and dead trees after the Ukraine war broke out,” said Laura Frader. “Now I’m working on a series about climate change and dunes collapsing. It’s all very intentional.”

Frader, who was a history professor at Northeastern University, has found affirmation in the collective. “I felt like a baby diving back into this,” she said. She learned to paint from her father, Saul Levine, whom she describes as a WPA artist. Almost half a century had passed between the time she painted alongside her father and her picking up a paintbrush after retirement.

The collective has helped her form an identity as an artist. “There are a lot of other people who are doing the same or similar things,” she said, “going from a very active, high-energy professional career to something different.”

“We all have different motivations,” said Mary Ann O’Loughlin, who chose to study the sciences instead of art as a university student in Canada. Still, she had dabbled in the creative space — mostly ceramics — while pursuing a career that spanned scientific research, high tech, and finally a job as a director of executive education at Harvard Business School. She still does consulting work, but art is becoming more of a focus.

O’Loughlin said her participation in the group isn’t motivated by a need for “validation” or “recognition” regarding her artwork. Instead, it’s a refuge from the disorientation and isolation that can accompany the transition away from a professional life — a transition that was further complicated by the death of her husband three years ago. For O’Loughlin, the question was, “How do you stay at home and paint?” The friendships she’s made in the collective helped pave a path forward. “It’s a great comfort,” she said. “We paint together in my studio or somebody else’s studio or outside.”

The collective functions like many groups of artists, where ideas circulate around pubs and dinner tables just as much as they do through art schools or formal meetings.

For their upcoming group show at the Commons — the collective’s second exhibition so far — group members worked together to promote their artwork by dividing into teams that took on marketing, curating, and the design of an exhibition publication. “It’s easier when it’s a group effort rather than doing it alone,” said Koch.

Despite having raised a challenge to Kitaj’s thesis during the meeting, Koch said the discussion motivated him to create a painting.

“There was something about everybody talking about doing their work and how people were improvising around what Karma was saying,” Koch said. “I can’t put my finger on it, but I wouldn’t have done this if it hadn’t been for the meeting. It just got things flowing. To me, that’s the nature of a successful collective.”

Group Effort

The event: Works by members of the Outer Cape Art Collective

The time: Through Nov. 10; opening reception Friday, Nov. 1, 5 to 7 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Commons, 46 Bradford St.

The cost: Free