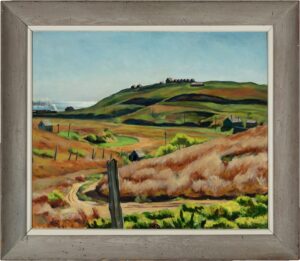

A broken fence post juts into the foreground in a painting of Corn Hill by George Yater. It’s a framing device that functions both formally and conceptually. The post’s prominent placement and detailed execution — its jagged edge and variations of silvery grays — help articulate the painting’s deep space but also betray how human intervention can interrupt a pastoral scene. Yater pushes the theme further in his painting of a late-afternoon Truro scene: a road cuts through the space, a train bellows smoke in the distance, telephone poles teeter along the edge of the hill, and, on top of the hill, a series of squat houses dominate.

“I was looking for a set of art objects where I felt there was a sideways or idiosyncratic approach to subject,” says Ruby T, the curator of “Land, Place, Identity,” an exhibition now on view at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. She pushes against an impression of Provincetown and the Outer Cape as “a beautiful neutral zone, separate from the rest of the world.”

The museum’s collection is reanimated to address stories of “entropy, survival, and reverence.” Here, landscapes, abstract paintings, and photographs tell a story of this place by eschewing a merely celebratory tone for something more complicated that brings settler colonialism, environmental degradation, and racial discrimination into view. The inclusion of works from beyond the Outer Cape — like Jules Aarons’s street photography — makes the case that this place isn’t cozily removed from the larger culture.

Yater’s scarred landscape connects to other paintings in the exhibition, including Lucy L’Engle’s Dyer’s Hollow, where a road also cuts through the landscape — this one flanked by fence posts that look like severed limbs. Her muddy, umber palette reinforces a somber mood, and the denuded hills and dunes in the distance speak of the area’s deforestation by early settlers.

The exhibition statement explicitly draws our attention to the area’s history of colonization by contextualizing Yater’s painting of Corn Hill in the events from which the area derived its name. This hill, where Pilgrims stole Wampanoag corn, is cast as a site of violation. Nearby, Alica Henry’s textile image of a larger-than-life Black head transposes the theme of a violated land to the body. Errant threads, stains, and fraying edges evoke the trauma experienced by Black bodies throughout American history. At first glance, Henry’s image seems out of place in this exhibition, but it raises the question: can we disentangle the social construction of the Outer Cape as an idyllic, utopian space from America’s history of racial discrimination and violence?

The theme of exclusion and corrective gestures of inclusion resounds throughout the exhibition, which will serve as a background for PAAM’s upcoming symposium (Nov. 9-10) of the same name. “The impetus for the symposium is to highlight practices and voices that we don’t center enough,” says Ruby T, who is organizing the two-day event. “It was a conundrum to then put a show together from a collection that skews pretty white.”

Notably missing from the show are works by Indigenous artists — a fact highlighted in the exhibition statement. There is an effort to include works by underrecognized women — such as an inventive still life by the surrealist painter Doris Lindo Lewis. The exhibition also includes work by Asian artists, including a large-scale abstract painting by Yako Yamamoto that provides a joyful note and a print by Seong Moy, who will be the subject of a presentation at the symposium.

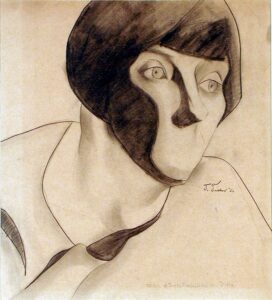

Janice Tworkov Biala is represented as a subject in an Edwin Dickinson painting and as an artist in a series of drawings, including two portraits of Shelby Shackelford, another artist associated with the town. One portrait of Shackelford looking upward with a dark shadow cast against the left side of her face echoes a similarly moody Nan Goldin photograph across the room, titled Bea Putting On Her Makeup, Boston. Portraits in the show serve to highlight the diverse communities that intersect with this place, including artists who lived here and the working people who shaped the land and community.

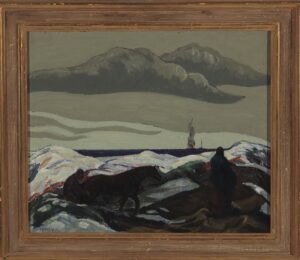

Ross Moffett’s painting Burning Schooner depicts a horse and two figures traversing the dunes and looking out at a burning vessel on the water. The darkened, downcast figures and calamitous event on the horizon remove any romanticism from this depiction of labor and industry.

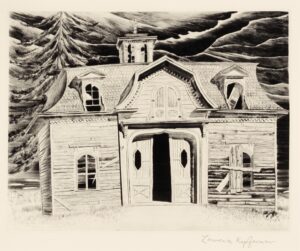

The exhibition also recasts depictions of New England architecture. There are no Edward Hopper paintings here of sun-drenched porches and white-clad houses. Lawrence Kupferman’s meticulous black-and-white drypoint print is instead a macabre portrait of a New England home in decline: the windows are shattered, shutters are askew, and the front doors swing open to reveal a gaping black hole.

Mary Fassett’s painting of a half-Cape evokes a similarly haunted atmosphere. Tree branches snake through the foreground of the painting like possessed spirits waiting to swallow the house. The legacy of colonialism is neither innocent nor stable, this painting suggests.

Decolonization is the buzzword of the moment in the art world and academia. Is this exhibition a step toward decolonizing PAAM’s collection? Maybe. Yet the show doesn’t succumb to the stridency and obsession with identity politics common to so much cultural production of the moment. “It’s not usually a great exhibition strategy to just put a show together based on identity markers,” says Ruby T.

The strength of this show is its diversity, which is displayed without tokenism or pandering.

The identity of the artists — and omission of certain groups — comes into focus, but it is the art objects themselves that animate the ideas.

Visually, the exhibition feels all-encompassing: there are bright abstract paintings, academic portraits, landscape paintings, street photography, and collages. The imagery is similarly diverse, and although our attention is focused on Provincetown and the Outer Cape, it travels to other places like Miami Beach or Stockton, Calif. in the photographs of Constantine Manos.

Through its inclusiveness, this view of the museum’s collection opens up a new pathway for understanding our cultural past and points a way forward that feels generative, nonhierarchical, and unbound from clichéd narratives or approaches to creating.

On View

The event: Land, Place, Identity: Selections From the Collection

The time: Through Nov. 18

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: $15 general admission