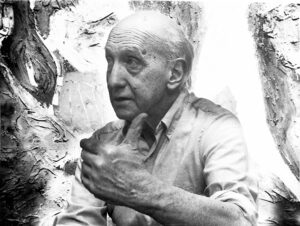

A show of paintings, ink-wash drawings, and lithograph prints currently on view at Orleans Modern Art captures a transitional moment in the career of George McNeil, an early participant in the abstract expressionist movement of the 20th century.

Although McNeil’s artwork retained the physicality of abstract expressionism, he rejected its fidelity to nonobjective painting. In Dancer #22, he paints a woman with an arm raised. The paint crudely defines the figure. Although he crossed the line into representation here, it’s clear that McNeil is excited about the material possibilities of paint moving across a surface. The painting hovers in a dynamic territory by applying the language of abstract expressionism to figuration.

Peter Kalill, who is both an artist and the owner of Orleans Modern Art, points out the way that McNeil incorporated a range of finishes in the painting: a flat earthy red sits against a passage of thick glossy white paint. McNeil’s physical manipulation of the paint is evident throughout — colors bleed together in pools of dried turpentine; other areas are splattered with globs of thick paint. Yet the figure remains as a persistent presence, gently raising her arm, palm upward, amid all this material chaos. This tug of war between the image of a figure and the vigorous exploration of paint and ink guides the whole exhibition.

Curated by Sam Tager, these pieces tell the story of McNeil’s embrace of the figure as a vehicle for making images and exploring existential concerns. Among McNeil’s peers — many of them central figures in the history of American abstraction — a controversy revolved around the question of whether abstract art should make reference to the observed world. It was an issue that divided McNeil from his early teacher Hans Hofmann and many other artists associated with Provincetown, where McNeil summered between 1948 and 1962 and kept a disciplined schedule of painting in the morning and swimming in the afternoon.

As abstract expressionism matured, its artists were faced with the challenge of how to move forward. By its nature, the movement emphasized bold gestures and youthful vigor. Many of these artists realized they couldn’t throw paint around surfaces forever.

A recent exhibition at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum charted the development of Sam Feinstein, whose aggressive gestures from the 1950s eventually gave way to a style that emphasized subtle variations of color and evoked cavernous spaces. Carmen Cicero, a Truro resident now in his 90s, was also steeped in abstract expressionism before transitioning to figurative expressionism. Willem de Kooning, a friendly acquaintance of McNeil, famously populated his canvases with female figures by the 1950s.

Other artists dug in their heels and remained committed to abstraction in its purest sense, avoiding any reference to figures, still lifes, or landscapes. These artists hewed more closely to the values of critics like Clement Greenberg, who admired the way abstractionists “relieved” color from any “localizing and denotative function.” Hofmann remained in this camp, as did many others like Helen Frankenthaler, whose paintings increasingly became typified by washes of color — evident in her Provincetown Series, which was recently acquired by PAAM. Others, like McNeil’s Provincetown friend Jack Tworkov, left agitated gestures behind for a more ordered, geometric language.

By the 1960s, the figure started to appear in McNeil’s work, although “almost fugitively,” says his daughter, Helen McNeil-Ashton. “By the 1970s, the figure is central to his endeavor,” she adds. The work on view at Orleans Modern Art covers this period.

As a teacher at Pratt and the New York Studio School, McNeil often discussed a theory about the interdependence of form and energy. As a practitioner, it was the human figure that invigorated his work with a fresh sense of energy. “The human form has too much power to be ignored,” he told McNeil-Ashton. “You have to return to the body because of its power.”

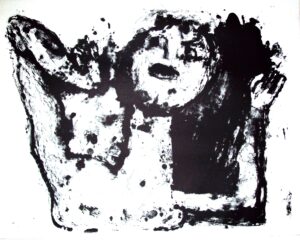

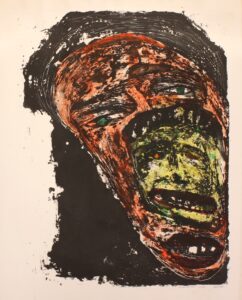

The figures in this exhibition feel more universal than personal. In a series of lithograph prints of human heads, McNeil’s titles make oblique references to who his subjects might be: one picture is a salesman, a few others are based on Roman busts. The grimacing blond in Elise Head feels pulled from a magazine. In the ink-wash drawings, many done during life-drawing sessions, the personalities of his subjects are more evident. In Rosalind, he captures the piercing eyes of the model. Yet taken together, this is a body of work emphasizing the everyman. It’s work about the human condition in a general sense, not a celebration of a particular community or particular person.

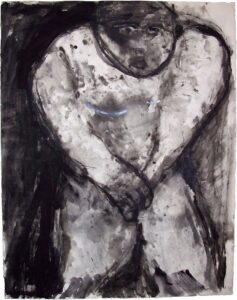

“He was widely read, steeped in art history, and interested in existentialism,” says McNeil-Ashton, who remembers dog-eared copies of Camus’s books lying around the house. The sense of existential dread is most evident in Double Head #1 and two images of a hulking man cowering. In Double Head #1, McNeil depicts a head inside another head, like an inner demon. The image is pushed against the edge of the page, furthering the sense of instability. In Anxious, the broad-shouldered man is similarly pushed up against the confines of the picture plane. He holds himself and gazes, terrified, at the viewer.

Anxious, like the other works in the show, was created with physical excess: the ink is alternately splotchy, sooty, and luxuriantly black. Perhaps this hulking figure is a metaphor: McNeil questioning the bravado of abstract expressionism, a movement long associated with virility and power. Had abstract expressionism, like the man in the picture, lost its edge? Had its physical bravado become masturbatory, turning inward? Regardless of McNeil’s intentions, the figures in this exhibition expand abstract expressionism’s legacy outward and introduce a degree of humanity and vulnerability into his work.

McNeil died in 1995. Throughout his career, he continued to expand his practice, even executing a series of paintings about disco culture in the 1980s, which he learned about from MTV. His figurative work from the 1970s anticipates these developments — as well as large cultural trends, like the rise of neo-expressionism — and reveals a creative spirit unwilling to wallow in past successes or modes of working but committed to invigorating his work with fresh energy and new ideas.

Dynamic Territory

The event: An exhibition of George McNeil lithographs and small works

The time: Through Nov. 6

The place: Orleans Modern Art, 85 Route 6A

The cost: Free