Jerome Greene paints what he sees. “I paint from my life,” he says. And although he grew up in Connecticut, studied in North Dakota, and toured New England as a roadie, that life — or at least the life he’s painted — is very much a Provincetown one. His studio here is filled with harborscapes, townscapes, landscapes, seascapes, and boats, along with a few nude figurative works.

Greene gets close to his subjects. He worked on Keith Rose’s fishing boat for one day to better understand what it’s like out at sea. “Hardest day of work I ever had,” he said about that day more than a decade ago. He’s both under the radar and in plain view — at the Old Colony Tap painting bands or working plein air on Provincetown’s harbor beaches.

Greene shows his work at Egeli Gallery, not far from his apartment on Brewster Street. He’s also the facilities director at the Fine Arts Work Center.

Sitting in a swivel chair in his studio, Greene explains some anomalies. On one wall, there’s a drawing featuring skulls piled on top of a green eye with a blue lid. “That’s going to be a tattoo for my nephew,” Greene says. There’s also a still life of Eastham turnips. He painted it 15 years ago, he says, to commemorate his hatred for turnips. More than 10 years ago, in his job interview at FAWC, Bob Bailey, who was then the work center’s facilities manager and chief engineer, asked Greene if there was anything he couldn’t do. “I can’t eat turnips,” was his reply.

Greene grew up around art. His father was a commercial artist and teacher — he painted in the same basement office where he graded papers, Greene says. “I’d sit on the stairs watching him, and he’d say, ‘Come down here, kid — what’s wrong with this painting?’ ” His father taught him to consider composition, color harmony, and perspective. “All those things are ingrained in me because they were part of my youth.”

His father’s painting of a sugar shack hung in the house in New Britain, Conn. where he grew up. Now it hangs in Greene’s studio alongside his father’s batiks and his own work, mostly oils.

It took him a while to be able to put his dad’s lessons into practice. At Pulaski High School, Greene was one of only two kids who were serious about art. But they were better known for tagging walls and messing up property. Greene is still grateful to the teacher who redirected the two boys’ attention with a mural project.

He followed a brother who had moved to North Dakota and landed at Bismarck State College, where he studied to become an art teacher, but he didn’t stick with that plan. Instead, after graduating in 1985 he took a job as a roadie, touring New England with the James Montgomery Band. That’s how he fell in love at a bar in Bourne and moved to Hyannis.

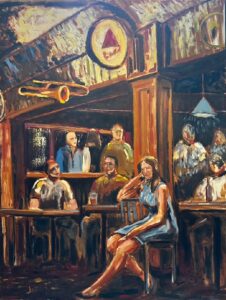

Greene worked as a contractor and as a doorman at Harry’s, the beloved blues bar in Hyannis that closed for good in 2010. Instead of paying attention to his doorman duties, Greene says, he began to draw, sketching the scene. A painting from one of his Harry’s sketches now hangs in his studio, the figures in motion lit by a glowing bar sign.

“Enough with the watercolors and acrylics,” Loretta Feeney told Greene in 1996. “If you want to be a serious artist, you need to start painting with oil.” He did.

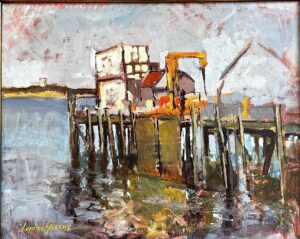

Provincetown Shore features Greene’s thick strokes of deep teal oil paint on the harbor. It’s an overcast day and the crimson of the American flag and rust red of a chimney play off the green stained pier. Navy and white stripes of an awning figure in the middle of the work. Houses lined up on the distant shore are rendered impressionistically.

For a while, Greene’s art and craft skills came together in a job at a framing studio, one that refocused him on his painting. He tried running his own gallery, Jerome Greene Fine Arts, in Dennis, but in 2007 the recession was looming and business was slow. He closed up shop and headed to Provincetown, where he moved into a studio space he’d been renting for years.

It was 2012 when Greene started working part-time as a building and grounds associate at FAWC. Now, as facilities director, he manages the center’s 30 apartments and 20 studios.

The summer is wild, says Greene. The studios, which are occupied by the writers and artists who come to town to teach the more than 60 workshops offered at FAWC during the season, turn over every week. Then in August come the returning residencies — short-term stays for past fellows and faculty.

A week ago, Greene says, he kicked on the heat at FAWC. Come fall, it’s his job, with help from Joe Fish and Nathaniel Doane, to make sure the place is ready for the arrival of the center’s fellows. He wants things right: “It’s one of the best and most prestigious fellowships in the world,” he says. It’s been going since 1968.

“I have worked my whole life to be irresponsible,” says Greene. “And what do they do? They put me in the most responsible job at FAWC.”

Somehow, Greene still makes time to paint. He is there for open figure painting sessions at Paul Schulenburg’s studio in Eastham — he helped start the group 20 years ago.

“I love my job,” Greene says. It’s cyclical and different every year, shaped by the interests that the visiting artists and writers bring with them. “I love the newness of everything,” he says. The 10 visual artists and 10 writers who are this year’s fellows arrived on Oct. 1.