If you want to see a fairy, says Andrew Warburton, all you have to do is find a four-leaf clover and place it on your forehead. He’s never found a four-leaf clover.

But there are other ways: look for a fairy ring — a patch of fungus that’s growing in a perfect circle. “Dance around it three times,” says Warburton. “Or possibly nine times. Nine is three times three, so it’s even more powerful.”

If dancing doesn’t work, there’s always fairy ointment, which you rub on your eyes to see fairies. “But I don’t think anyone’s going to find that,” says Warburton. It’s a cruel paradox. “You have to get it from the fairies.”

Warburton grew up on fairy stories in Bristol, a city in the southwest of England. In 2007, he moved to the U.S. Living in Massachusetts and attending Tufts University, he says, a new wealth of fairy lore spread out before him.

In 2012, he visited Cornwall. “It’s a very magical place,” he says. “There’s a lot of folklore about pixies there.” He brought home a pixie charm: a small, seated pixie made of nickel. That same year, he heard news of the Mohegan tribe in Connecticut, which was fighting to prevent a housing complex from being built on their ancestral land — “mainly on Mohegan Hill,” says Warburton, “which is where the Little People live.”

The term “Little People” was historically a euphemism, he writes in the introduction to his book — a name meant to make fairies seem less threatening. The Mohegan tribe called the Little People who lived under the hill “makiawisug.”

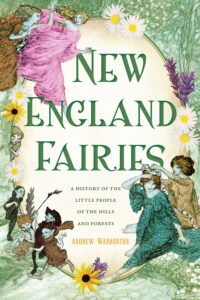

The Mohegans’ situation piqued his interest in fairy lore, Warburton says. Almost 12 years later, he began researching and writing a collection of stories, published in August, titled New England Fairies: A History of the Little People of the Hills and Forests. He’ll be in Provincetown to promote it on Sept. 21.

Warburton took six months to travel the length and width of New England. “I was pretty obsessive about it,” he says. Often, he ventured into the woods alone. He went to Mohegan Hill to see the folkloric home of the Little People for himself.

He visited Sherman, Conn., where he met a local woman in her 90s named Ann Price. She told him the story of Perry Boney, a man who people thought was a fairy — or at least that he could speak to fairies. “I thought it was going to be a legend,” says Warburton. But Price’s aunts and uncles and grandparents supposedly knew Boney. “That surprised me,” he says. “What also surprised me is that she basically dismissed the folklore. She thought it was all nonsense. But even she didn’t really have an answer for why Boney became associated with fairies.”

Warburton connected with Ray McKenna, who writes often about the Irish immigration to Providence. “He told me about his great-grandmother’s encounter with banshees in Rhode Island,” says Warburton. “She came over after the Great Famine and settled in a mill town in northern Rhode Island.” In the town where she lived, there was a bridge. “She said these banshees were coming over the bridge.”

Banshees are floating fairies, Warburton explains. They often wear white gowns and have long white hair. They wail for the dead. “I suspected that maybe she was talking metaphorically,” says Warburton. She saw a lot of death, he says — first the famine, then epidemics of cholera in the U.S. “Maybe she just meant that death was coming into the village, right?” But McKenna was convinced that she meant it literally: she saw the banshees.

Though Warburton, who lives in Cranston, R.I., has never seen a fairy, he says plenty of the people who come to his book events claim they have. “Most have been older women who remember things that their Irish grandparents used to say about fairies,” he says. “One woman that I met said she didn’t necessarily see fairies, but she could feel them. I spoke to another person who said she had a ‘brownie’ in her house. A brownie is a kind of hobgoblin.” A hobgoblin is a household spirit, alternatingly helpful and mischievous, appearing in English folklore.

Fairies can be scary, says Warburton. “Etymologically, the word ‘fairy’ goes back to the idea of fate. They can ruin your life.” In many stories recounted in his book, fairies make people sick; they hold people captive; they play cruel tricks.

“There was one woman in Marblehead,” says Warburton, “who said she was so confused by pixies that she stumbled around at night. She could see her home, but she couldn’t get to it.”

Of course, some people aren’t afraid at all: Dutch immigrant Dora van Gelder Kunz, who died in 1999, was “a kind of David Attenborough of fairyland,” Warburton writes. She studied her subjects closely and wrote a book in 1977 filled with her descriptions of them: The Real World of Fairies. Gelder Kunz wrote of fairies as vaporous beings of “pure feeling” who tended plants using their vibrational energy and “golden light.”

Whether or not fairies exist, people have kept them relevant through stories passed down orally and in writing. Warburton can think of a few reasons why. “For one thing, it’s just escapism on the most basic level,” he says. “The stories create magic in the landscape around us.” Put simply, he says, “it’s entertaining.”

Fairies are more than the subjects of entertaining tall tales, though, says Warburton: “They open up our minds to the spiritual.” And fairy stories connect us to our ancestors who told them. “There’s a level of historical interest,” he says. “Even if you were a complete atheist, you could still be interested in the history, right?”

For Cape Codders, Warburton provides one such history lesson: “There’s a triangle of paranormal activity in southern Massachusetts,” he says, “called the Bridgewater Triangle. Everyone is like, ‘Oh, the Pukwudgies are there.’ ” But according to the earliest Wampanoag stories, says Warburton, the Pukwudgies, those two-foot-tall violent pranksters, actually live among the bulrushes in Cape Cod’s Popponesset Bay.

The current residence of the Pukwudgies remains a mystery, but no matter. “Rather than a documentation of paranormal events,” says Warburton, “I wanted my book to be a history of belief.”

Andrew Warburton will be signing books at the Provincetown Bookshop on Saturday, Sept. 21 at 2 p.m.