Ted Chapin pulls the guts out of machines — “eviscerating them,” he says. That’s how he assembles his intricate wall sculptures, which combine machines like typewriters with natural elements like wood, conch shells, starfish, and eroded pieces of iron.

Chapin says people are becoming more like machines and machines are becoming more like people. Our identities are being dissolved into the machines we have created.

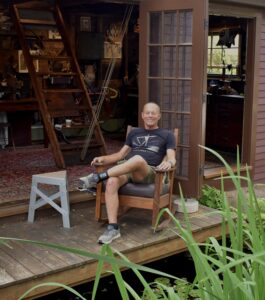

“It’s hard to know where one ends and the other begins,” he says, sitting in a chair overlooking the koi pond outside his studio on Pearl Street.

“Digital machine intelligence now rules us,” he says. “The machines are now possibly overwhelming us.”

His adding machines and typewriters, dating from between the 1920s and 50’s, sourced from a collector in Palm Springs, Calif., where Chapin lives eight months of the year. “An adding machine is the beginning of machine intelligence,” he says. “You push keys, and an answer comes back at you.”

In AI Running Rampant, a sculpture about the battle of man versus machine, Chapin used a hand sander and belt sander to make bits and pieces of adding machines and 1980s superhero action figures shiny and new. It’s an array of torsos, arms, and legs, with pieces of the sculpture heading in all directions, making us wonder if it will come alive.

Panic at the Bourse, made from the sandcastle molds children play with at the beach, is a metaphor for stock market mayhem. “Capitalism is another manmade machine that is out of control and destroying us, largely through climate change,” says Chapin. “It’s like AI in that way: something we created that’s overwhelming us.”

The same goes for the ripped-out adding machine sculpture Financial Bubble, made from fake pearls, chandelier crystals, and pieces of toy skyscrapers. The piece looks like it could collapse in strong economic headwinds. “So much of capitalism is about numbers evolving out of numbers,” says Chapin.

An architect for 28 years, Chapin says sculpting allows him to practice “right brain structural engineering” — finding intuitive ways to hold pieces in space. He wants to make sculptures so complicated you can’t figure out how they’re made or how they function.

Chapin has been disassembling and reassembling things his whole life. In childhood, it was action figures; today, it’s the copper wall and detailed face he added to the side of his Pearl Street home.

Chapin’s Harnessing Natural Beauty is a piece in the round that uses sea urchin shells from the Shell Shop in Provincetown. He drilled horseshoe crabs as armatures at the edges of the piece; he calls it “a William Blake gesture.” Chapin says the work is heavy and delicate: “The worst combination! I’ll have someone hold it steady to bring it over to the gallery.”

In many of his sculptures, Chapin uses springs as a metaphor for construction, suggesting movement and action. But he found he could solve certain structural problems with tension that he couldn’t solve with compression.

Chapin uses an antique adding machine from the Roaring Twenties in Swimming in Gold. “America in its heyday,” he says. “Today, America is a leader, but all the products are being made somewhere else. America doesn’t make tangibles like this anymore. It’s the end of an era.”

Chapin looks to the work of Provincetown artist Paul Bowen for inspiration for his wall installations.

“Joseph Cornell’s work has also had an influence on my work,” he says. “He was telling stories with found objects. He was the first artist to make it big without doing any painting; he just did constructions.”

Chapin was born in 1950 in suburban Cleveland but was raised in Manchester, Conn. His father was an aeronautical engineer during World War II. In 1951 his father went to work for United Technologies in East Hartford, running the largest wind tunnel in the world and designing aircraft. Chapin has a bachelor’s degree in economics from Yale University (1972) and a master’s in architecture from the University of Pennsylvania (1975). He has spent the last 30 summers in Provincetown.

He likes a clean, modern environment in which to build his work. His studio is highly organized so that he can find what he wants in an instant. It’s like a library of sorted bins: bins of typewriter pieces, bins of toys, bins of springs.

Although he started making art seriously by age 24, it wasn’t until he was 53 that Chapin became a full-time artist.

He says the work he’s making now is a little apocalyptic. “I see myself as an illustrator,” he says. “I have these pieces, and I’m building them into something that tells a story.”

Nuts and Bolts

The event: An exhibition of works by Ted Chapin

The time: Through Aug. 10

The place: Berta Walker Gallery, 208 Bradford St., Provincetown

The cost: Free