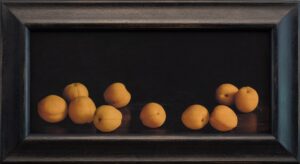

Ten apricots, a bunch of grapes, three blueberries, a skull tipped over, a half-empty glass: these subjects would be just as at home on the walls of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam as they are within the framed prints of the Nyack, N.Y.-based artist and photographer Jefferson Hayman.

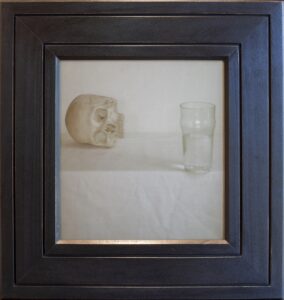

With its attention to mortality, precarity, and temporality, Hayman’s work — photographic prints paired with artist-made or vintage frames — sometimes seems to be nodding to the Dutch masters. And I Am of This Earth — a title he took from a line in the 2012 film adaptation of Anna Karenina — is one such pared-down take on a classic still life.

“As humans we are all just mostly water encased in a fragile container,” says Hayman of the imagery in the work. “All the while, death waits patiently in the immediate background.”

The appeal of Hayman’s work is not just in its rich symbolism or its contemporary subversion of the old master techniques of drawing and painting, which Hayman studied at Kutztown University near where he grew up in rural central Pennsylvania.

It is also, perhaps more compellingly, in how Hayman uses a frame to transform the infinitely reproducible medium of photography and to create a narrative of association through visual variability.

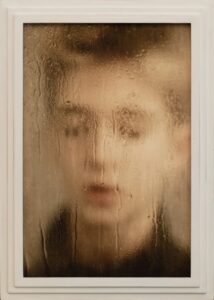

He makes some of the frames by hand, and the resulting intimacy is clear, especially in Portrait of My Son. The subject is Hayman’s 12-year-old son, Beckett.

“I asked him to stand in the shower and photographed him with the glass shower partition between us,” says Hayman. “It was still coated with water, so it acted as an interesting distortion filter that somewhat obscured his identity.”

This kind of distortion speaks to the way the interpretation of even the objects most familiar to us can be transformed by a filter, a frame, or a rearrangement. In Hayman’s work, interpretation is turned on its head when each pairing of frame and image is placed in conversation with others on the gallery wall.

It’s not a jigsaw puzzle; it’s more like Jenga: interactive, three-dimensional, teetering on the edge between perseverance and total collapse. How the pieces are arranged and what narrative emerges depends on a careful touch and an intuitive, almost premonitory vision.

Hayman has something like that. He trusts that the gallerists showing his work do, too. He likes to give them control of the installation. “It almost gives the images a whole new context and a whole new life,” says Hayman.

For his upcoming exhibition at William-Scott Gallery in Provincetown, which opens with a reception on July 5, he did that with director Brian Galloway.

“The aesthetic is very fitting of the old Provincetown, bohemian kind of vibe,” says Galloway of the juxtaposition of size and subject matter present in Hayman’s pairings. “They feel serious.”

Tiny frames that might have once preserved a loved one’s likeness now touch a different kind of infinity: a 4-by-3-inch slice of seascape, for instance. The variety in sizing, composition, and framing in Hayman’s work is not only aesthetically motivated but also intentionally principled: a first-time collector with $300 to spare could buy one of the smaller pieces. “I want people to be able to afford my work,” says Hayman.

To select vintage frames for the exhibition, Hayman says he took the history of Provincetown and its storied relationship with the sea into context. The result is about 30 one-of-a-kind “pairings.”

“A lot of frame choices speak to the later part of the 19th century,” says Hayman. “I tried to envision the people of that time: the sea captains, the sea captains’ wives, the workers, the workers’ wives.”

Delving into the history and culture of the places he exhibits is common practice for Hayman. For a show in Paris earlier this year, he chose a selection of vintage French frames. For this show, he used several 19th-century frames, including the circa 1870s silver gilded frame that houses Infinity Sign.

“The vintage frames lend color, design, and character to any artwork they surround,” says Hayman. “They are not only affordable but also carry a deep history.”

Instead of sourcing frames for $5 each at the Chelsea Flea Market, which he did at the start of his career, Hayman now uses a small army of pickers who comb estate sales and antique shops and text him with a photo and price when they come across something interesting. The sourced frames have added up. At any one time, Hayman says there are 400 to 500 frames in his studio.

“When I see a vintage frame, I will know instantly which image of mine will pair well with it,” says Hayman. “When combined, they become something greater than their parts.”

30 New Pairings

The event: An exhibition of work by Jefferson Hayman

The time: Through July 17; opening reception Friday, July 5, 6 to 9 p.m.

The place: William-Scott Gallery, 439 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free