Madonna is depressed. Not because — as in her appearances as the Virgin Mary since the Renaissance — she knows that her kid, the baby Jesus, is going to be crucified. She’s depressed because she broke her leg and she’s been stuck on the couch for weeks, unable to get on with life as usual.

The Madonna in Kathryn Engberg’s Madonna is the painter’s sister, Sarah. The pose is classical, but the sensibility is decidedly not. The Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi, who Engberg says painted “very empowered and very violent women,” would undoubtedly approve.

“I wanted to explore this idea of the Madonna’s worth being based on her motherhood and see what it would feel like to take away her child,” says Engberg.

Encountering the downcast eyes, pouty lips, and slightly slumped shoulders of a beautiful woman of childbearing age in a Renaissance-inspired dress, a viewer conditioned by the patriarchy of the visual art world — where most representations of women have been created by men — might expect a child to materialize on the canvas.

Finding none, she encounters the empty space and the potential it offers: in one interpretation, valuable time for a woman to experience self-pity and frustration that — God forbid — is totally unrelated to her capacity to reproduce.

Madonna is one of 10 new paintings by Engberg featured in “The Quiet, the Vulnerable, the Truth,” an exhibition of work she has completed since she moved from New York to her hometown of Salisbury, Md. last year. The exhibition opens with a reception at Simie Maryles Gallery, 435 Commercial St., Provincetown, on Friday, June 21 and is on view until June 28.

The paintings feature her sister, her cousin, her students, and family friends as models. “It’s really just people I’m spending time with,” says Engberg, who paints exclusively from life.

“Technology is an amazing tool, but it adds a layer of modernity that I don’t always love in my work,” she says. “Photographs really restrict the way someone moves and the micro-changes of expressions.”

Her mother, Lois Engberg, and grandmother, Barbara Beauchamp, are also representational painters — they specialize in florals and landscapes. She grew up in their studios, and she says that influence and the exposure it offered to a creative community in Maryland enabled her to pursue art seriously as a career.

Engberg spends dozens of hours with a model, sharing conversation and silence. “By the end of that time, my perception of that person and their presence and features has shifted,” she says. “I’ve really analyzed every aspect of them.”

She has worked this way since her time as a student and teacher at Grand Central Atelier, an art school in Queens, N.Y. devoted to classical drawing and painting. One of her teachers, the painter Patrick Byrnes, introduced Engberg to gallerist Simie Maryles about seven years ago. Engberg’s work stunned Maryles. She and Joshua Van Dereck, her son and the gallery’s managing director, brought Engberg into the gallery’s fold soon after. Engberg, now 29, was 22 years old.

“I found all of the artists from the atelier to have the technical understanding to be outstanding, but you can’t teach poetry,” says Maryles. “Sometimes her paintings come in and they just take my breath away.”

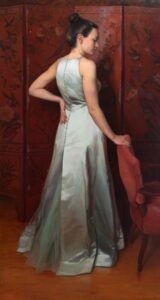

The centerpiece of the exhibition is Interlude in Viridian Green, a portrait of a woman behind a dressing screen in a moment of contemplation. She seems to know she is being observed, but she doesn’t care about captivating. Swaths of her silk dress produce a mirroring effect, catching light and shadow and daring viewers to consider what is being reflected and why, precisely, they’re looking.

Six feet tall, it is Engberg’s largest portrait to date and demonstrates a command of execution, draftsmanship, tone, and structure. As Maryles says, you can see it in the hands. It took five years to complete.

“The Quiet, the Vulnerable, the Truth” bears the aesthetic touch of “Fashioned by Sargent,” a recent exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston that explored how John Singer Sargent captured and represented the distinctive identities of his subjects through their clothing. Hoop Skirt and Contemplation, two other Engberg portraits in the exhibition, were made shortly after Van Dereck gave her a catalog of the Sargent show.

Like Sargent’s, Engberg’s portraiture reveals a refined and elegant taste. Unlike Sargent, however, she avoids the superficial luxury of the Gilded Era, and her work is not buoyed by caricature and eroticism. It is urgent and sarcastic and embodies the erect spine of feminist virtue.

“She brings the refinement, patience, and technical class of a 19th-century master painter together with an assertive — even to the point of being aggressive — 21st-century political outlook,” says Van Dereck.

The effect is undeniably cathartic. In forsaking the male gaze, Engberg shows us where visual art is headed: women as the actors and producers of their own assured representation.

“There was always this underlying discomfort with the way women were being represented and the value being placed on them,” says Engberg. “I wanted to show something different.”

Quiet, Vulnerable, True

The event: An exhibition of paintings by Kathryn Engberg

The time: Through June 28; opening reception Friday, June 21, 7 to 9 p.m.

The place: Simie Maryles Gallery, 435 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free