In 2020, Sarah Dineen unearthed a 19-square-foot painting that she had made as a graduate student at the School of Visual Arts in New York. “I call it my adolescent painting,” she says. “It was an awkward-stage painting that just never worked.”

Yet the painting contained a shape that had been reappearing in her work for years. She talks about it now as a malleable image, at times suggesting a keyhole, a microphone, or a tree. She cut the shape out from the oversized canvas and found a path forward with it. Although once peripheral to her practice, the shape — a circle atop a vertical rectangle — has since become her dominant motif.

Dineen grew up in Brewster. She returned there in 2022 after living in Beverly and then in New York City for 12 years. In her Provincetown studio at the Fine Arts Work Center (where she started working in April as fellowship artist services manager), the walls are lined with large-scale paintings. The surfaces are dark and dense, and, in most of them, the keyhole shape dominates the center of the composition.

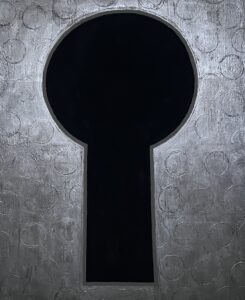

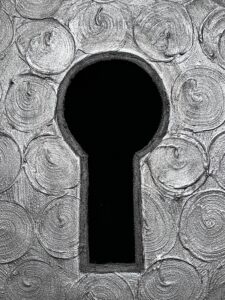

“The shape is a place and a thing,” she says, standing in front of a recent painting that towers over her. “With small paintings, it’s harder trying to convince the viewer there’s space, but if a painting is life-size, some of that work is done for you.” Painted in a combination of acrylic and gouache paints, the central shape has a velvety matte finish that sucks in all light. It feels like an infinite void that one could step into.

“This space can hold a multitude of things,” says Dineen. She’s not comfortable assigning it a definitive meaning. “I’m following something through the material and the shape,” she says. “It’s a search without expecting an answer.”

They’re portals into the subconscious — a space that’s neither positive nor negative but profoundly deep. This pursuit leads inward but also feels universal in its mystical and philosophical implications. Questions of existence are at stake here. “It’s very human to follow a symbol that has some kind of meaning,” Dineen says.

Whereas the central shapes in her paintings provide an illusion of deep space, other areas of the paintings appear as impenetrable surfaces. During a trip to England a year ago, she found herself fascinated with castles, armor, keyholes, and distressed metals. “I felt like I was on some kind of treasure hunt,” says Dineen.

In her painting Portal, she used silver paint and a repeated circular shape to suggest chainmail armor or the surface of a shield. In other paintings, the shield motif is more explicit in both the titles and the rounded forms that encircle her vertical shapes.

The reference to shields and armor reads as both decoration and metaphor in the paintings. Dineen is captivated by how “these things of war are so ornate and beautiful.” In her work, she mixes pigment into acrylic molding paste to create textured swirls on the surface of her canvases, reminiscent of decorative stucco finishes on walls.

In Shield Portal #1, the physicality of the impasto surface and its metallic sheen exist in dramatic tension to the deep space conjured in the central black shape. This carefully calibrated play with materials suggests broader tensions between history and timelessness.

As an artist, Dineen capitalizes on strengths endemic to painting, namely its paradoxical ability to create sumptuous, dense surfaces while also articulating spatial illusion. She jumps fully in on painting’s longstanding conversation about materiality and transcendence.

And yet she often finds herself under the spell of sculpture. Some of her favorite artists are sculptors: Richard Serra, Louise Nevelson, and Magdalena Abakanowicz. In London, she found herself powerfully moved by an exhibition of Abakanowicz’s work at the Tate Modern. “You just feel the emotion in the weight of the material,” says Dineen.

In her Provincetown studio, she renders her signature shape in three dimensions in a pair of towering black sculptures. They’re created from foam and painted black.

“My rule right now is that the sculptures need to be light enough that I can personally move them around,” says Dineen. The sculptures position the shapes as objects rather than spaces. The form is also slightly different than in the paintings: the vertical shape is longer, the circle smaller. As such, it reads more like a body or monument.

Dineen’s obsession with one shape doesn’t limit her but rather opens up seemingly limitless possibilities that span painting and sculpture and works both small and large. She speaks about the meaning of the work being embedded in the material — which it is — but there’s also meaning embedded within her process of working repeatedly with a singular shape. Like a meditation or a mantra, it leads her inward and illuminates through focus, repetition, and austerity.