For three years in the late 1970s, Rosalind Pace worked on a series of paintings: eight large canvases in black and white that would read like a visual language. She chose eight because book pages are cut in multiples of four.

At the time, she was living in Easton, Pa. and did not have a proper studio. So, she pushed all her living room furniture against the walls, spread the floor with newspaper, and propped each canvas up against her fireplace. She remembers her two sons carefully walking their bicycles through this obstacle course as they came in the front door of the house.

“Ultimately, you sense it,” Pace says about her abstract expressionist technique, “but to sense it you have to know quite a bit: to know how colors react to each other, how to create something dynamic, not static, and how to create tension.”

Pace titled the work The Good Promises of the Lord because she could describe her artistic discovery only as experiencing a state of grace. “I don’t have a religious background per se,” she says, “but I do believe in a mystery and a universal energy we can feel but we’re never going to understand.”

Now, standing in front of the eight giant canvases, which have not been shown in decades, Pace says, “I didn’t want any specific language on these — I wanted it to be suggestive, to create the desire to understand something. There’s that gap between wanting to understand and realizing that some things are always going to remain mysterious.”

The series now hangs in the Provincetown Art Association and Museum as part of her show, “Rosalind Pace: Poiesis, Five Decades of Collage,” on exhibit through June 23 with a celebratory reception open to the public on Friday, May 10 at 6 p.m. In semiotics, poiesis describes the process of a person bringing into being something that did not exist before.

“The first time I was able to see this piece on one wall, I saw how the canvases wanted to get together, how the black areas wanted to connect, how the free-painted areas might have once been part of one painting — they were not — and how the calligraphic elements wanted to say something that everyone could read,” Pace says.

She saw how the partial strips of calligraphy could stand next to large black rectangles and feel “like sound was coming out,” she says. “I wanted the parts to be distinct, moving with a sense of struggle, dance, and promise toward some kind of resolution that would happen in the viewer’s mind and not on the canvas.” The linen canvas underneath this series comes through at times, faded from the decades.

Pace says that a person who saw these early works at a 1981 opening in Allentown, Pa. told her, “There are places in here that I really wouldn’t want to be.” Her response: “Uh-huh! You think we’re not put on this Earth to be challenged?”

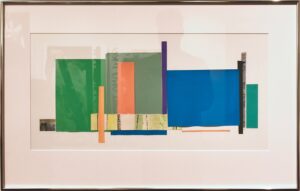

Dream Pages Series With Blue, Green, and Orange from 1978 is a collage with papers. The work connects to Pace’s background in literature. “I make poems,” she says. “I’ve always been interested in books and the turning of the pages. A poem is line by line by line, an unfolding of images — passages in sequence, and journeys.”

Stretched along the walls of the gallery, Pace’s work feels like an endless open book, pages spreading out not so much like an accordion but sliding out from under each other. Her work pays attention to “scale, small events, and big spaces,” she says.

The show at PAAM chronicles five decades of Pace’s practice: the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, 2000s, and 2010s. But the show isn’t arranged chronologically. “I don’t think you could imagine a chronology by looking at them,” she says. “I’ve been working with the same intuitive impulses right from the beginning.”

In the 2000s and 2010s, Pace took some of her early paintings off stretchers and cut them up. “I had a whole table full of scraps and raw materials that I could use,” she says. “For a few years, I used the pieces of acrylic on canvas for these collages.” Those cut canvases are now stand-alone pieces in the show.

Pace was born in Minneapolis in 1939. Her parents moved to Syracuse, N.Y. a year later, then to Washington, D.C., where her father worked for the Navy Dept. as a civilian during World War II, developing questionnaires and designing ways for the Navy to collect data on personnel.

She graduated with a degree in English from Brown University in 1961. “I got my diploma in the morning and got married that afternoon,” she says.

“It was during the Vietnam War,” she says. “The war was a terrible mistake. There was absolutely no way I was going to support it in any fashion.” She joined the Peace Corps and went to Afghanistan from 1962 to 1964.

Pace first arrived on Cape Cod in 1973 to take a workshop in abstract expressionist techniques at Castle Hill with artist Budd Hopkins, whose daughter, Grace Hopkins, is the curator of Pace’s PAAM show. At the time, Pace was living outside Philadelphia, taking courses at a local art center. She asked the instructor, “Do you by any chance know of a place where I could go for a couple of weeks and do nothing but paint? Preferably some place beautiful?”

“Those two weeks changed my life,” she says. “I was among people who became my tribe. Budd was a brilliant teacher — everything I learned about art I learned from him. He was the one who convinced me I was an artist. He knew exactly where to point to show you what was working and why. The next summer he taught collage.” Pace came to Castle Hill every summer after that until she moved to Truro in 1991. She has a studio next to her house.

Pace taught poetry and art workshops at Castle Hill for many years and eventually taught at PAAM for the five years before the pandemic hit.

She had worked as the director of the renowned Long Point Gallery in Provincetown after Mary Abel retired. “Imagine every day being surrounded by that art,” she says. “Every single artist’s work contributed something to my work — you can’t help but absorb.”

Pace says her work celebrates a struggle to understand what the universe is telling us and how things fit together. “The resolution will always lie beyond the work itself,” she says, “in our imagination and in our dreams.”

You Sense It

The event: “Rosalind Pace: Poiesis, Five Decades of Collage”

The time: On exhibit through June 23; reception Friday, May 10, 6 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: General admission $15