In the summer of 1949, a series of avant-garde art seminars and exhibitions took place in Provincetown. They covered a wide range of subjects, from painting and poetry to architecture, jazz, and psychoanalysis. The event, called Forum 49, was programmed by poet and painter Weldon Kees and featured renowned abstract artists of the day, including Hans Hofmann, Robert Motherwell, and Adolph Gottlieb.

Seventy-five years later, “Remembering Forum 49,” an exhibition curated by artists Grace Hopkins and Cid Bolduc, is now on view at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. The exhibition showcases mid-century abstract paintings and sculptures by artists who were here during that memorable summer.

Forum 49 kicked off with a discussion titled “What Is an Artist?” led by Hofmann and ended with a controversial symposium, “French Art vs. American Art Today,” organized by Gottlieb.

“In 1949, panel discussions and events were held every Thursday from June through the end of August at 200 Commercial St.,” says Hopkins. Hopkins and Bolduc are treating the current exhibit as a kickoff for their own creation, Forum 24 — an upcoming series of programs based on the seminars and exhibitions of Forum 49.

“This exhibit features artists who were showing work in Provincetown at that specific moment,” says Hopkins. The works are mainly from the PAAM collection, but some are from The Cape Cod Museum of Art and private collectors.

Robert Motherwell’s undated color lithograph Black Douglas Stone captures a sense of unfinished business. Inside a steel-blue rectangle is a black rectangle with rounded unfinished edges. Four thin white lines appear inside the black rectangle. Three of the lines are vertical and the bottom line is horizontal, creating a grid. The position of the central line creates a vertical quarter stripe in the sequence. The absence of a fifth line, which would create bilateral symmetry, is poignant. The same thin lines appear in La Casa de Mancha, a second work by Motherwell in the show. These gridlike lines read as an unfinished blueprint.

Gaps of black in the central rectangle create a sense of the incomplete. Absent lines, strange abstractions, and imperfect, unfinished shapes are signatures of abstract expressionist painting.

Motherwell delivered a lecture, “Reflections on Painting Now,” during a Forum 49 symposium. (It was later published in The Writings of Robert Motherwell by University of California Press.) “The whole universe — external and internal — constitutes potential objects,” he said. “Abstract painting, in choosing a new class of objects, enriched human experience.”

In 1949, Motherwell was just beginning to create his most notable works, his Elegies to the Spanish Republic. As the most outspoken intellectual of the abstract expressionists, he did not hold back in stating his intentions. “One of the minor tasks of the modern mind,” he said in his Forum 49 lecture, “might be a new mythology of the heavens.”

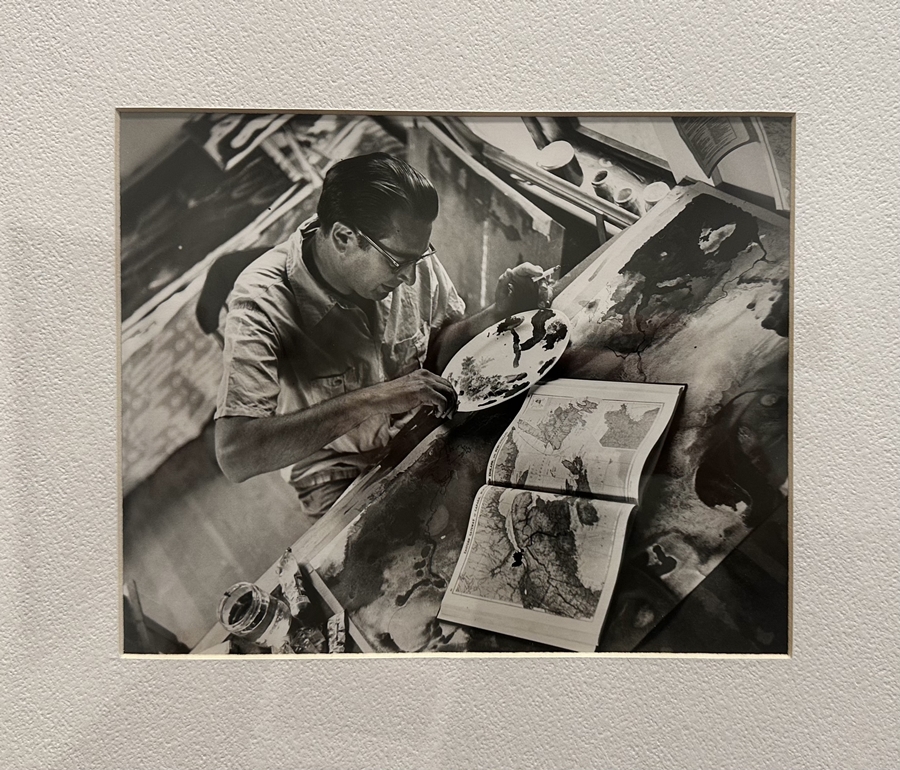

Jules Aarons was the photographer on the scene. His silver gelatin photograph Portrait of Artist Lawrence Kupferman shows the painter mixing colors in a dish with a cigarette burning in his left hand. The photograph’s perspective is diagonal, inviting the viewer into different sections of the picture plane almost in congruence with the tilt of Kupferman’s head. The painter is using a map that says “Eastern Gateway of Canada, New England and Newfoundland” for his abstract work.

“Aarons took pictures that summer and gave them to PAAM,” says Hopkins. “His pictures are of artists in the dunes and people in the exhibitions standing in front of the artworks — they give context to the time.”

Adolph Gottlieb was a central figure at the forum and chose the panel for the final symposium on French and American art. He was interested in unintelligibility — illegible painting and automatic drawing. His Imaginary Landscape was finished in 1955, six years later. In this small work we see one of Gottlieb’s signature red circles. To the left of the red circle is a black circle with its top chopped off, almost like a black teacup with no handle viewed at eye level. Judging from the titles of similar works, this black shape could be a buoy or a planet. The bizarre color and character of the shapes create a space for us to question assumptions about what we see.

The background of the top half of Gottlieb’s canvas is the blue of a sky on an overcast day. But the sky is too muted for the sun to be this red — something is off. Maybe we are not seeing what we think we are looking at.

The bottom half of the work has a dark base layer with choppy strokes of gray and black and brushed dabs of white, red, and orange from the shapes above. It’s as if Gottlieb threw the top half of the canvas in a blender and poured it out on the bottom half. Black lines resemble the capital letters of an acronym. The writing is illegible.

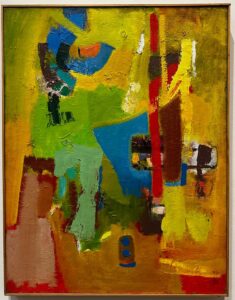

Lillian Orlowsky’s Untitled, an abstract oil painting from 1955, sings of a colorful Provincetown summer. A teal circle swirls over a patch of grass green. A faded blue trapezoid may be an in-ground pool. A stripe of cayenne red pops out of the golden yellow fray. A swoop of banana yellow grabs the eye. All the paint and sand from her studio seem to have been thrown onto the canvas. A stroke of white from a pallet knife turns blue at the end.

A sense of the unfinished and unrefined exists here. We see unmixed color only partially mapped out. Her layering and experimentation give us a sense of process in this shock of color and shape. Sixty-nine years later, this eye-catching painting does not make us squint as it might have fresh out of the studio in 1955. Time has done its work.

Fritz Bultman’s bronze sculpture Wave, from 1977, could be a two-headed snake gliding along Provincetown Harbor on a slice of cantaloupe after a fire turned the assemblage charcoal black. Or is it a fearless black snail racing across the breakwater? It’s neither. The piece plays with form, thickness, thinness, curves and openings, rough and smooth surfaces. The cut at the very end of the sculpture’s snout is final, giving us a sense of the sublime. The way the piece curls around itself makes us consider our mortality.

Pumpkin, an oil painting from 1964 by Karl Knaths, has a strong architectural foundation. The canvas is boldly mapped out by lines of black oil paint that frame each plane. The central pumpkin is broken into rigid shapes. Knaths is not blending color here. He is confronting us with the question of color clearly drawn out and exaggerated. A plane of gray for shadow, a rectangle of peanut butter, two planes of sand, a lemon-lime oval the color of crabgrass; a half-moon sliver on the pumpkin’s left side is the color not of a pumpkin but of pumpkin pie. The painting is surrounded by a tempest of deep blues and greens. There is energy here in the quick sketchiness. We are left with questions of what is what — and how much must we identify.

This painting is about Knaths himself and his own sense of what he painted. Shape and line are clearly defined. There is clarity in the picture even though we may not be able to identify what exactly is being given to us. We, the viewers, are being included in the process. We are offered new definitions in the absence of recognizable description.