“You remember how to start?” Lauren Byrne asks a student. Byrne is giving a quick painting tutorial. “Start with the color note you see the best, and everything after that is an adjacent color note.

“Put the shadow note in, and then the next note in — doesn’t have to be exact,” she says. “This is the first pass.”

By “color notes,” Byrne means the calibration of hue, temperature, and intensity in the colors painters mix on their palettes as they apply each mark on a painting.

Whether the result was seen as shadow or light was a foundational consideration of painters Charles Hawthorne, who founded the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown in 1899, and of his student Henry Hensche. Later, Hensche had his own school, which he called the Cape School of Art.

The studio session Bryne is leading on this February morning is offered by a newer Cape School of Art, one reconstituted by artists who had studied with Hensche.

She had opened the door to its North Light Studio in the woods off Route 6 early because the day before, a nor’easter had blown through Provincetown dumping snow on the ground and knocking out power. She knew there would be artists ready to brave the winter weather to paint.

Layered against the cold in a hoodie and vest and wearing a patterned knit headband, her white latex gloves covered in cadmium yellow paint, Byrne helps the artists in the studio set up for the day’s session. During the quiet months, painters gather here informally four mornings a week to develop their sense of color and light.

People drive to Provincetown to study from all over the Cape, says Byrne, who lives in Truro. Sometimes she stays there all day, lingering as the light in the studio changes.

Byrne moves around the studio, taking in each student’s work with patience and care. The nonprofit school’s free winter sessions are “a give-back to the community to get people used to our way of painting,” she says.

Before becoming a full-time painter, Byrne owned a small garden design firm outside Boston. She moved to the Outer Cape in 2011 after studying color at the Cape School with Hilda Neily, her mentor. She carries that mentoring impulse forward in the sessions she now leads. “We all look at each other’s work and make our color adjustments.”

The painters in the studio sessions are mostly working on the question of depth of color. That’s what matters most, says Byrne, in distinguishing a painting’s light plane from its shadow plane — the expanses of light and dark you see before taking into consideration depth, perspective, line, value, and shape.

“Morning light is different from afternoon light,” says Byrne. “You’ll see that around noon, in the studio, the light shifts. You have to be disciplined enough to not chase color.” The idea is that you can’t keep shifting the color notes of your painting along with the light. Better to come back tomorrow at the same time of day.

To set up painters for still-life and block studies, Byrne uses a collection of vases, bowls, and bottles that live on a white bookcase in the back of the studio. Many of these were Henry Hensche’s props, she says.

An old wooden sign hanging from the crawl space above the easels and props says “Hawthorne School of Art.” In the front of the studio on a shelf by the window are an unplugged fan, half a brick, orange medicine vials for oils, wet wipes, tissues, a fern-green vase with fake flowers, a hummingbird figurine, and a functioning tea kettle.

The studio smells of oil paint. The heater beneath the window flashes its green light. It’s covered in drops of paint. Classical piano plays on the radio in the background.

It’s afternoon now, and the light has shifted in the studio. Snow falls on cars outside. “That reflection from snow really throws light in here,” says Byrne. Looking at a blue vase, a pale peach cup, and a white plate resting on a Prussian Blue blanket, she notes how those colors change and shift on a day like today.

Students at the Cape School paint only in natural light, and they never use black. They paint in oil on Masonite boards and use palette knives.

Drawing can be important to getting a painting right.

“I struggled painting the Somerset House Inn on Pearl Street,” Byrne says. “I went home one night and drew it a hundred times to work out the perspective.” But it’s not what students do in the studio. “If you’d like to draw, we draw in the evening,” she says.

“We work two paintings a day — one in the morning and one in the afternoon,” Byrne says, setting herself up to paint alongside others in the session. “It’s very much a gray day in the studio so my notes are going to be deeper. You want your colors to sing, even if they’re in the shadow plane — get as much contrast as you can.”

Kathi Siar works on a still life close to the window. “I was a waitress at the Lobster Pot for 38 years,” says Siar, who is also a sculptor. She has been painting here for a year and says Byrne’s help matters “all the way through a painting.”

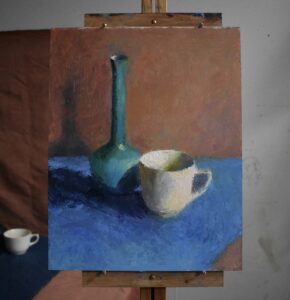

Siar’s palette-knife rendering of a white teacup next to a teal vase is elegant in color and shape. The teacup’s shadow merges with the shadow from the base of the vase and stretches across half the board. The sand-colored background turns to canyon red where the stem of the vase casts its shadow on the back wall. The tablecloth is cerulean but becomes midnight blue in shadow. The light is captured in notes of yellow in the white cup.

Danny Skahen and his husband, Brad Mallow, have been painting at the studio for two years. Skahen says he makes about one painting a week, each one taking him about 16 hours. “Our first year we were just doing studies,” he says. “We’re really painting now.”

Byrne makes her way over to Skahen’s still life of a yellow flower in front of an orange bowl. “I don’t think this orange is as warm as you have it,” she says. “I think it’s going to be more of a rose — that’ll cool it down.”

If you go outside and squint your eyes to find the color of light falling on the landscape, you will begin to understand what this serious study is all about, Byrne says. “By squinting, you are taking away the focus on any one area and recognizing color notes only. In the light, or in the shadow, how warm or cool is it? Can I mix the color that I see?”

In Brad Mallow’s still life, the white oval of a plate takes up most of the picture plane. He used French ultramarine for the background shadows to create contrast and bring the plate forward into the light. In front of the plate, to the left, is a small peach-colored pitcher that reflects a note of green. To the right is a golden pear.

“I haven’t touched the pear in four days,” says Mallow, “and I need to put the stem on it.” The pear throws a shadow on the plate.

Byrne checks out his work. “You really got to push this light. You only have color to indicate light,” she reminds him. “That’s what we’re doing — pushing color and trying to indicate what the light is going to be.

“Here is something to really pump that shadow note,” she says, pulling out a tube of Michael Harding Indanthrone blue oil paint. “You want to go deeper.”