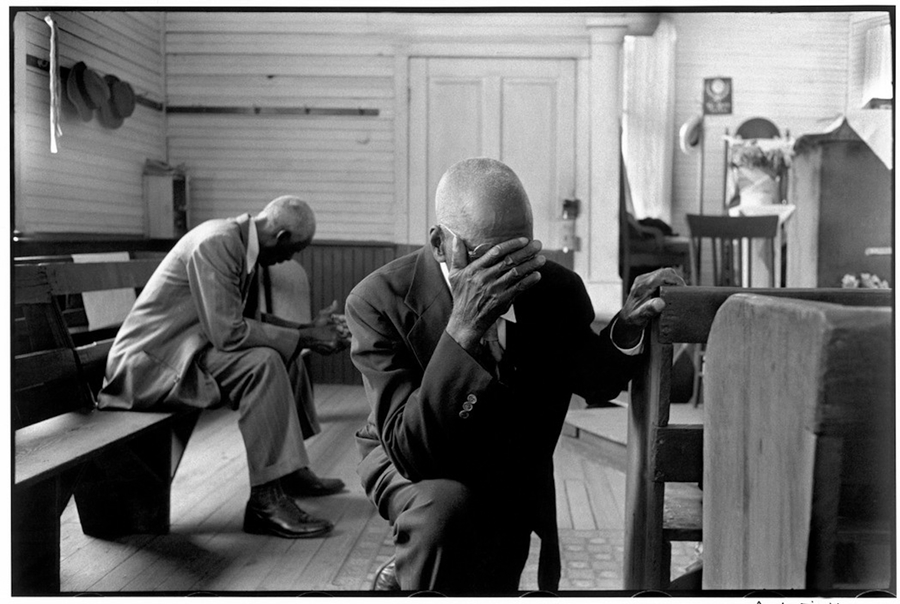

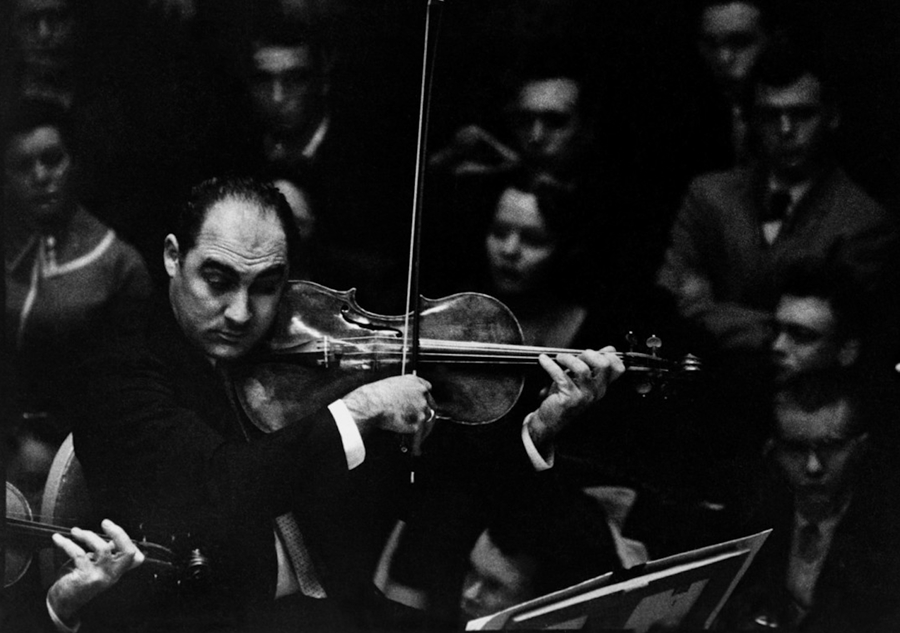

Two men kneel in prayer in a modest church, one shielding his face from a light perhaps only he can see. A single note played by a group of classical musicians is frozen in a geometry of taut strings and drawn bows. Three figures at a fairground multiply and merge into a tangle of colors and shadow in the raking light of a summer afternoon.

It isn’t readily apparent that these images, with their disparate subjects and formal qualities, were made by the same photographer. But there’s something they all have in common: the instinctual capture of an unrepeatable moment suspended in time.

For Constantine Manos, the pursuit of this “decisive moment” — to use photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson’s term for how movement, framing, and composition come together in a photographic instant — has been the focus of a career that spans seven decades. This month, an exhibition at the Wellfleet Adult Community Center will give Outer Cape audiences a rare opportunity for a closer look at Manos’s work.

A resident of Provincetown since 2008, Manos was born to Greek immigrant parents in Columbia, S.C. in 1934. His first significant body of work, made when he was still in his teens, was a suite of photos taken in 1952 on Daufuskie Island off the South Carolina coast. The island is the home of members of the Gullah Geechee, an African American community whose coastal isolation has enabled them to preserve aspects of the language and culture of their enslaved West African forebears.

The photographs capture bucolic moments in the lives of their subjects: a woman tending crops, three children walking beneath an oak tree dripping with Spanish moss in the heat of a Lowcountry afternoon. It’s an astonishingly mature body of work for an 18-year-old.

Michael Prodanou, the photographer’s husband and partner of 61 years, says that Manos’s intent with the Daufuskie photographs was simply to see things and record them. “He saw his subjects as people living a beautiful life, fishing and farming,” he says. He also identifies a shared spirit between Manos and his subjects. “It’s not the same thing, of course,” says Prodanou. “But as a child of immigrants, Costa knew what it felt like to be an outsider on some level.”

And even if Prodanou says that Manos “wasn’t trying to change the world” with his photography, the pictures are of a piece with the anti-segregation editorials Manos was writing around the same time as a college student at the then-segregated University of South Carolina. “Many members of the community eventually left the island after industrial dumping up the coast destroyed their livelihoods,” says Prodanou. “So, Costa’s photos are a valuable historical document, too.”

In 1953, the Boston Symphony Orchestra hired Manos to document its summer program at Tanglewood. Within a few years, he became the orchestra’s official photographer. The assignment would culminate in the publication of his first book, Portrait of a Symphony, in 1961.

Much of Manos’s early work shows the influence of Cartier-Bresson, whose photographs inspired the young Manos to purchase his first camera — a Leica, the same camera that Cartier-Bresson used. Manos would again follow in his idol’s footsteps in 1963 when he became a partner in Magnum Photos, the international photographer cooperative which Cartier-Bresson cofounded.

Unlike Cartier-Bresson, who retained a lifetime devotion to black-and-white photography, Manos eventually decided to begin shooting in color. The change resulted in the decades-long series American Color, selections from which are currently on view in the community center exhibition.

First published as a book in 1995 (a second volume followed in 2010), the series shows Manos expanding his work to scenes from all over the U.S.: abandoned boardwalks in Atlantic City, carnival celebrations in New Orleans, pastel street scenes in Ft. Lauderdale and Miami Beach.

Here, as in Manos’s earlier works, people are the focus. “I am a people photographer and have always been interested in people,” said Manos in an undated interview with Magnum. “I have been very serious about photographing people as individuals, as human beings. I don’t think I have ever taken a photo without a person in it.”

But the human presence in Manos’s photographs is often implied and elusive. Faces are obscured, bodies are cropped or viewed from behind, and individuals are represented by body fragments or shadows.

While his pictures frequently depict activity and movement, there is seldom drama. Instead, Manos captures less obvious moments — almost the moments between moments — in which the visual elements of the photograph come together in dynamic balance. “Costa always said that the fraction of a second that he captures will never happen again,” says Prodanou. “And that’s what photography is all about.”

There’s an echo of his older contemporaries Robert Frank and William Klein in Manos’s occasionally mordant view of the United States and its people. But Manos is, at heart, a sympathetic artist. While American Color shows some of the tackier and more boisterous aspects of American culture — the motorcycle rallies, pageants, and marching band parades — they are never depicted with condescension. Instead, there’s a lyricism and tenderness that softens even the most hard-edged of his compositions: witness the ethereal light that bathes a sidewalk in shades of blue and cyan in Manos’s 1981 photograph of Miami Beach.

Manos also took photographs for Life and Look magazines and for various corporations — which frequently used his photos in their annual reports — well into his 70s. Many of his photographs became part of preeminent collections around the world, including those of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and, closer to home, the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, which mounted a retrospective exhibition of his work in 2013.

Manos, who turns 90 this year, has stopped making new photographs and relies on his husband to be present at his shows. Prodanou says there remains a huge body of work still waiting to be discovered and exhibited. The pictures on view in the current show in Wellfleet, he says, are “only a small fraction” of the ones in the American Color series: “Well over 200 have been published in the two books. But we have hundreds more in the studio. And Costa printed every one of them himself.”

And like those early photographs in South Carolina and Boston, every one of them tells a story. “Pictures speak their own language,” says Prodanou. “The photos have to speak to you. It’s up to us to listen to them.”

Editor’s note: Because of a fact-checking error, an earlier version of this article, published in print on Feb. 29, misspelled the name of Michael Prodanou.

Capturing the Moment

The event: American Color: Photographs by Constantine Manos, curated by Robert Rindler

The time: On view through March 30, with a reception for the artist on Sunday, March 3, 3 p.m.

The place: Wellfleet Adult Community Center, 715 Old King’s Highway

The cost: Free; see wellfleetcoa.org for information