Abraham Storer was standing in a cemetery in Gliwice, Poland in the fall of 2020. He wasn’t there to mourn but to paint — positioned with easel, canvas, and palette on a tree-lined path. His subject was an archway, behind which the sun shone and fiery foliage collected on the ground.

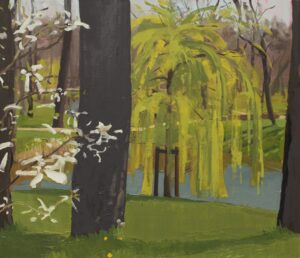

The arch is a motif in Storer’s paintings: it appears either explicitly or subtly, as in Weeping Willow, where the tree’s wispy branches slope symmetrically downward. Always, though, it frames the painting from the inside out, drawing the viewer’s eye first toward the painting’s center and then incrementally toward its edges. As our eyes zoom out, we notice how one element of the composition relates to another. In this way, Storer’s paintings — most of which are landscapes — encourage us to notice the intricate ways the world arranges itself before us.

Storer says a woman approached him while he was painting in the cemetery — a burial site for Soviet soldiers where most of the headstones have no names and where the steely feel of socialist realist architecture dominates. “She said something about how I was painting inside this place that commemorates death, but I was looking out at the light,” says Storer. “She said the painting was like a journey into life.”

That painting is titled Arch, and the austerity of the scene it depicts is softened by the oranges and greens Storer has used for the foliage, hues that are vivid and airy. Storer’s light touch has a strong effect. Arch is on display this month as part of the artist’s solo show, “Paintings of Poland,” at the Wellfleet Adult Community Center (715 Old Kings Hwy.). Curated by Robert Rindler, the paintings in the exhibition are arranged more or less by the season in which they were painted, from spring to winter, and together they complicate our associations of some seasons with life, others with death.

In Brown Field one finds a vast stretch of grass, all of it scorched by sun and heat. It invites you to lie down and succumb to the lethargy of a humid day. Looking at it, you can feel the deadening stupor of summer, a season prized for its supposed liveliness. It hangs next to Winter, which is all white and pink, colors as sharp and spry as the brisk winds of January. Winter was painted in the same graveyard as Arch, and the white gravestone portrayed in it serves not only to demarcate where the dead lie but also to pick up the warm colors of sunset. In this interplay of ground and sky, light and shadow, life and death meet. It’s hard to tell where one begins and the other ends.

All the paintings in the current show were done between 2019 and 2021, a period when Storer, who contributes frequently to the Independent, was living in Poland with his wife, Agata, and their two children. While they were there, the pandemic enveloped the world.

“It was a time of dislocation and frustration, of waiting and loss,” Storer says. “There are some places that touch you very personally very quickly. But Poland was not one of those places for me. Until I met Agata, who is from Poland, I had no connection to the country, and so it felt like a total blank slate. It was challenging to try and locate myself in Poland’s landscapes.”

Storer’s attunement to landscapes — his ability to notice the small details within them that others miss — stems from his upbringing on Cape Cod. He was born in Wellfleet and spent his childhood there and in Dennis, always observing the environment.

“I identified very early with Wellfleet’s creative community,” he says. He began painting and drawing at Dennis-Yarmouth Regional High School in classes with Amy Kandall, who now teaches at Nauset High. Storer then attended Brandeis University and went on to get an M.F.A. at Boston University in 2008. Since then, he has moved around a lot, developing a nomadic habit he says he’s found difficult to break.

After getting his master’s, he taught in Indiana for a year. In 2011, a Fulbright fellowship took him to Israel, where he met Agata. For the next decade, the couple were back and forth between Israel, New York City, and Poland until the summer of 2021, when they returned to live in Storer’s father’s house in Wellfleet.

The paintings in the show, though they range widely in color and composition, depict the same handful of locations that stitched together Storer’s seasons in Poland: the graveyard, the field near his house, a nearby pond, the view of shrubs through his kitchen window. “These places were my refuge in Poland,” he says. “Painting them was a way to anchor myself and to find something personal there.” All the paintings are tinged with the peculiar mix of longing and loneliness expats often feel. In them, one can see Storer’s process of finding flashes of recognition in the unfamiliar.

Two paintings of the same place — the graveyard in autumn or in winter, the field from afar or a budding tree within it close-up — differ more than they converge, revealing that even that which is the same is never statically so.

“These paintings are about impermanence,” Storer says. “That’s why there are so many trees in them. Each painting shows a tree in a different stage. I paint trees the way other artists paint portraits. They’re like human figures, always changing and moving and with different personalities. The landscapes are the same way.”

For the past few years, Storer has been painting landscapes in Wellfleet. “My paintings based here are my attempt to map my idyllic childhood memories of this place against the reality that I’m experiencing here now,” he says. “There’s a lot of beauty on the Outer Cape, but there’s also a lot of banality. I’m fascinated by that contrast: beauty inside mundanity. And I try to capture that contrast in my work, placing something sacred next to something profane. Here, on the Outer Cape, our experience of this landscape as completely natural has in large part been constructed and manicured by the National Seashore. And I want to show that dual reality. It’s a wildly beautiful place, and it’s also a cultivated one.”

In the exhibition, three paintings hang to the side of the rest. Each one shows a landscape through a window — like the arch, the windowpanes frame the photo from the inside out. And as with life and death at the cemetery, the boundary between inside and outside is made porous in these domestic settings.

The branches of a pussy willow come into a view from behind a cabinet, but they seem to reach outside, joining the shrubs and the fragile spring sun. An amaryllis flower blends in with the window, as if it could be balanced on the sill inside or springing up from the earth outside. Either way, it functions as a lever from one place to the next.

“Like windows and arches,” Storer says, “a good painting is a portal into another reality.”

Expatriate

The event: Abraham Storer solo exhibition, “Paintings of Poland”

The time: Through Feb. 29; opening reception Sunday, Feb. 11, 3 to 5 p.m.

The place: Wellfleet Adult Community Center, 715 Old Kings Hwy.

The cost: Free