On the first floor of the Provincetown Public Library, in the magazine section, is Henry Hensche’s Portrait of Margaret Mayo Expecting Motherhood. The woman’s eyes are pained and sad yet vital and a piercing blue, like the whirlpools of fabric in her dress. Other than the fact of her impending motherhood, her history is absent. But it turns out that she wrote her own.

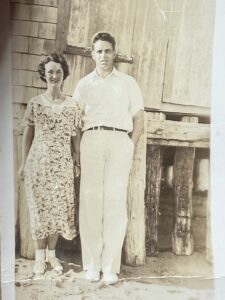

When Margaret Mayo died in 2009 at 100, she left hundreds of pages of a handwritten memoir that had been transcribed by typists she hired in town. Her youngest child, David Mayo, keeps the pages — marked with little edits in blue ink — in labeled three-ring binders. He lives in a cottage he built by the beach across from the red house he grew up in on the East End of Commercial Street. The desk at which his mother wrote for several hours every day is the centerpiece of his living room.

Mayo remembers his mother as an avid reader whose trips into town for groceries involved paddling from the East End to the wharf and back in a sealskin kayak — a memento from one of Admiral Donald B. MacMillan’s 33 expeditions to the Arctic. She had four children; two died shortly after birth. After her husband, Herbert, died young in 1966, she found solace in writing, daily swims in the bay, and working at the Pilgrim Monument.

David Mayo recently offered the Independent an opportunity to review Margaret’s unpublished archive. In the selections about Provincetown, which she wrote at 90, Margaret details the history of this place and her evolving relationship to it. Her family had moved from Dorchester to Provincetown full-time around 1924 when her father was appointed chief of police. She was 16.

The family rented the house of a widow affectionately called “Ma Dunham.” Margaret writes that the porch was a meeting place for many in the art world. At that time, there was a “cosmopolitan atmosphere” emerging in Provincetown, as the destabilization wrought by World War I attracted itinerant artists and writers who had previously summered on Grecian isles and Italian coasts.

Provincetown was not entirely new to Margaret. Her father had grown up here as the fourth of six children born to a Portuguese fisherman and a Canadian midwife. Of that time, Margaret writes, “Birth Control was unknown … so families flourished, wanted or not.” While the seafaring grandfather was away, the midwife grandmother tended to friends and neighbors in “fruitful but over-extended households where conditions often got out of control,” largely due to the “demon Rum.”

This grandmother, along with her daughters, is described by Margaret as high-spirited, adventurous, and self-sufficient. Her Aunt Etta, who ran the fashion department at the Modern Priscilla magazine in Boston, tended to “outgrow” husbands. She also advised her brother, Margaret’s father, to give his wife and daughters “freer rein outside the house.”

Mayo reflects: “This I appreciated but felt I could handle my problems with Papa myself. In fact, sometimes, I felt sorry for him, as I knew, deep within me, that no one would ever truly control me.” In asides like this, Margaret’s archive traces the arc of her burgeoning womanhood as she adopts her own identity and forms friendships away from the watchful gaze of her father.

She recalls a dance put on by the Knights of Columbus at their clubhouse, which brought out a crowd of Portuguese residents a few years older than she. Her father escorted her to and from the dance and sporadically peeked in the windows, but when he was away, she was freed by anonymity. She lied about her name, telling her dance partner she was “Angelina from New York.”

“I became the heroine of every romantic novel I had ever read,” writes Margaret.

Reminiscing about another party she attended with classmates from Provincetown High School, she writes: “The air was blue with cigarette smoke, liquor flowed freely, the Charleston was being performed with vigor and couples were moving up and down the impressive stately staircase.”

One conversation during a dune walk with an unnamed painter friend, for whom she modeled on occasion, seems peculiarly prescient. The friend presented Margaret with an idea: “That of a sperm bank to free women from the domination of men. Each sex could then go its own way,” writes Margaret. “When the idea did hit the general public, years later, I thought back to the young teenage girl who had figured out such a bizarre idea while treading the same sands once trod by the Pilgrims who were also looking for a ‘new, different world.’ ”

At the same time, the hyperconsciousness of a woman perceiving herself and being perceived through the lens of pervasive patriarchy splinters Margaret’s writing. When Navy patrolmen stroll through Provincetown and smile at her and her teenage friends, she writes that the girls knew to acknowledge them with a certain “toss of the head” that indicated they were “good girls.”

In this memoir of Provincetown, Margaret also writes about Donald MacMillan, Eugene O’Neill, and other dominating male figures of the era. But again and again, her attention is drawn back to the lives and thoughts of early 20th-century women and girls — from her midwife grandmother and bohemian aunt to a young devotee of Gandhi and to “Sooz” and Ellen, the daughters of John Philip Souza and Mary Heaton Vorse, respectively.

In her writing, Margaret is transformed from the object of a portrait to the portraitist, outlining and coloring the lives of those whose stories would otherwise have been brushed aside by the sweeping hand of married life and the expectations of domesticity. The details she amplifies not only grant insight into qualities she admired and the gendered constraints of the era but also demonstrate an undeniable impulse toward self-empowerment of a proto-feminist variety.