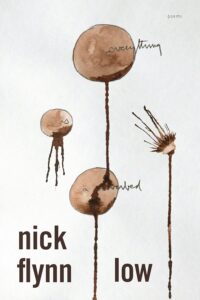

Nick Flynn’s Low, his sixth volume of poems, is perfectly tuned to winter’s meditative months. Published in November by Graywolf Press, the collection consists of poems of varying lengths that form chains of meaning. Flynn refers to each of its six sections as “sides,” an homage to the music significant to Flynn’s inner jukebox.

“There’s the Indie rock band called Low,” Flynn says. “Low is also a great David Bowie album, a song by R.E.M., and there’s the advice that Grace Paley gave to young writers: ‘low overhead.’ ” Writer Grace Paley, who died in 2007, was a beloved Fine Arts Work Center teacher.

“There is always a little music in every poem,” he says. “Sometimes it’s just the structure of how you’re chasing the sounds. And repetition is a big part of music.” Flynn has also made music: last February, he collaborated with Guy Barash on the album Killdeer, on which his poems become part of the sound’s fabric.

Flynn, born in Scituate, splits his year between Brooklyn and Texas, where he teaches creative writing at the University of Houston each spring. He also maintains deep ties to Provincetown, home to long-lasting friendships that date back to his fellowship and subsequent job as writing coordinator at the Fine Arts Work Center throughout the ’90s. It was among the Outer Cape’s dunes, shore birds, and tides that he first called himself a poet.

Flynn published his first poetry book, Some Ether (2000), shortly after his second FAWC fellowship; that year, he was selected as a Guggenheim fellow. His memoir Another Bullshit Night in Suck City (2004) earned him a Pen International award and was adapted into the 2012 film Being Flynn, starring Robert De Niro and Julianne Moore as Flynn’s parents.

In Low, poems form narrative and metaphysical puzzles, often hovering around the idea of desire. What is it? Where does it come from? Flynn finds answers in arcane definitions from the Greek, Latin, and even Old Norse. In “Notes on Want,” he writes, “The verb want came into use around 1200 (wanten: be lacking, be without; borrowed from Old Norse vanta: to want; see wane). The original notion of ‘lack’ was extended to ‘need,’ & from this developed (in 1706) the sense of ‘desire.’ What happened in 1706 to transform need into desire?”

One of the poems in Low, “I Am a Town,” is “written for the eponymous film, a documentary about Provincetown, by Mischa Richter,” says Flynn. His attachment to the town and to Richter’s art is lyrically expressed: “I am a town held together by paint/ one day you’ll forget I exist// I am the book that no one has read/ silverfish made me their home// … skateboarder kids live on the beach/ their piano lives under a tarp// everyone struggles just out of sight/ we leave and come back like the tide.”

Coinciding with Low’s release was an exhibit titled “Sacred Trash” of Flynn’s collages in an Austin gallery in partnership with the Texas Book Festival. Low in hand, gallerygoers could connect the title of a poem to a collage on the wall. “Every book I do has a lot of side projects around it,” Flynn says.

“One thing about having a collage show with a book — the book is relatively cheap, while the collages are $500 each,” Flynn says, his voice a musical lilt. This was the second public exhibit of his collages; the first was in 2021, at Richter’s East End Provincetown gallery, Land’s End.

Flynn’s poems are also inspired by the turbulent life of his mother, who, when Flynn was in his early 20s, died by suicide. Annually in mid-December, Flynn writes a poem on the anniversary of her death. This year, he was inspired by a version of Hamlet in which actor Sandra Hüller played double roles: Prince Hamlet and his father, the murdered king, who appears as a ghost. Melding the interdependent characters, substance and shadow, “made much more sense,” Flynn says.

Another poem inspired by Hamlet, “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” echoes the drowned Ophelia. It begins, “Field, rust, stone. Each night you/ return to the same place — a woman// lies naked in a field, the way her/ body holds itself tells you the way// she would hold you. She floats on/ the grass, each blade has roots// reaching to the river below. Hidden,/ that might be the word, she might be// your mother, …// … now she’s a stone you visit/ once a year or so, …”

Flynn’s daughter, Maeve Lulu Taylor Flynn, also frequently appears in his poems. “Sacred Trash” begins: “My daughter scribbles out/ a stranger’s face in the news-// paper, — maybe// she saw something in his eyes,/ something she didn’t want// to see …” The poem’s midsection describes ancient crypts, scraps of paper buried alongside grocery lists. “Nothing// has changed. My daughter/ draws a picture of the two of us,// side-by-side, our arms wide —// this is what I’ll remember,// I tell myself.”

Low is dedicated to writers, musicians, and many other familiar Outer Cape characters, including his wife, the actor Lili Taylor, and their daughter.

Flynn will spend time in Provincetown this summer, again teaching a workshop at FAWC entitled “Memoir as Bewilderment” and a separate course at Castle Hill with artist and naturalist Mark Adams. He also hopes to present his newest project, using artificial intelligence to activate text into images as it’s read. This fall, in New Orleans, Flynn performed poems from Low before a sizable audience of fascinated techies. His was the only live performance there. For Flynn, even futuristic technology opens doors to the possibilities of collaboration.