In her 1954 book about Cape Cod’s land and culture, Where Land Meets Sea, Clare Leighton describes herself as “a Britisher by birth” and a Cape Codder for a decade. For decades thereafter, she rented a cottage on Wellfleet’s Cove Road in the summer and returned often in the winters. She died in 1989, but her presence is still notable in town. Her stained-glass windows flank the altar at Wellfleet’s Methodist Church. Her wood engravings — for which she is most famous — are displayed at the Cape Cod 5 Bank in Wellfleet, Julie Heller Gallery in Provincetown, and the Wellfleet Historical Society.

Leighton’s career as a wood engraver first brought her to the U.S. in 1929 when she gave a lecture at Harvard. She felt drawn to America for its “vitality,” and in 1939, at age 41, she relocated from England to the American South. “I needed to go somewhere as remote from England as possible,” she wrote in a memoir published posthumously by her nephew.

She spent nine years in North Carolina, then settled in Connecticut. She continued to travel as an illustrator: Peru, Canadian lumber camps, and throughout New England. She avoided cities and “the exciting agitation of America.” In Wellfleet, she found her ideal setting: a place of quiet for sustained concentration; a rich landscape; and land-based industry, one of her favorite subjects.

This interest is evident in the two prints hanging in the lobby of the Cape Cod 5. In Oyster Houses, Cape Cod, she depicts the oyster shacks that once stood along Duck Creek. Leighton’s take on this motif displays her virtuosic attention: the shingles on the shack, the texture of the sand. The picture feels vertiginous, with zig-zagging angles directing the eye to all corners of the page. At the top, gulls fly upward, extending the scene beyond the page.

Leighton was a dogged researcher of the natural world and rarely relied on photographs for visual information. “I remember one winter I spent on Cape Cod,” she wrote. “Warm inside the house, I knew that if I was in doubt as to the exact shape of a gull I had only to go down to the harbor and watch one as it flew.”

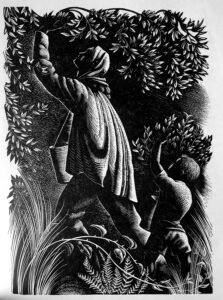

Cranberries, a circular image also at the Cape Cod 5, is from a series she created of 12 prints depicting New England industries. Commissioned by Wedgwood, an English dinnerware company, the prints were used on limited-edition decorative plates. Julie Heller, the Provincetown gallerist, bought a set of them in 1970 when she was just out of high school. She has since purchased more of the plates, which she sells at her gallery, along with some of Leighton’s prints.

“She was a master of wooden engraving,” says Heller. “She had a very sensitive eye for things happening on Cape Cod and the water.”

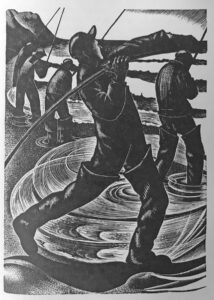

Heller donated a print, The Clam Diggers, to the Wellfleet Historical Society and Museum. “Everyone in Wellfleet can relate to this picture,” says Dwight Estey, a member of the museum’s board. “She found touchstones in her work.”

The print is dominated by three men digging clams in the foreground, but, by using a high horizon line, Leighton moves the viewer through the landscape. It’s a holistic vision that she builds on in her writing, where she details everything from the anatomy of a sea robin to Manuel Enos, a Portuguese man with “an intimate — if unscientific — knowledge of berries.”

Leighton initially took up wood engraving to support herself, but it soon became a passion. “I was spellbound with the feeling of creating light,” she wrote. “I was able to imitate the first day of Creation.”

Leighton’s first illustrations were for her father’s stories of the Wild West. Both her parents, Robert Leighton and Marie Connor Leighton, were writers. Her father had artistic inclinations but had to sneak into the upstairs nursery to paint, away from his wife, “who would have scolded him ruthlessly for neglecting his money-earning writing,” wrote their daughter.

Leighton never had children and devoted herself to her artwork. Her godson Bob Arnold observed Leighton’s working habits when she stayed in the Cove Road cottage owned by his grandparents. “We had strict rules when Clare was on the Cape,” says Arnold. “We weren’t to disturb her when she was working.”

When Arnold was a boy, Leighton was working on When Land Meets Sea and wrote about blueberry picking excursions with him and his mother. “The hours pass as we pick,” she wrote. “Robbie is tired, and we have put him to rest under a bush, on a bed of soft grass.”

Joan Hopkins Coughlin, a Wellfleet artist, also remembers Leighton. “I loved the way she looked,” she says. “There was no one else that dressed like Clare. She had auburn hair braided on each side of her head that she would roll up to look like earmuffs. She always wore embroidered peasant blouses with a wide neck and puff sleeves,” which she paired with gathered skirts and sandals. “She was very British but very colorful too,” adds Coughlin.

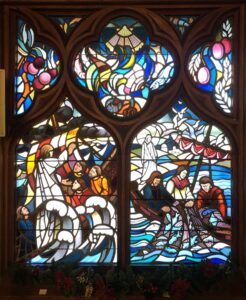

Leighton finally brought color into her work when the Bishop of Worcester asked her to create 33 stained-glass windows for the Cathedral of Saint Paul. The project consumed her, and she brought the knowledge back to Wellfleet. In 1966, she created two windows for the Methodist Church in Wellfleet, commissioned in the will of Annie B. Higgins.

Those first two windows for the church, titled Night and Day, feature angels amid Cape Cod imagery including a lighthouse, swirling waves, seagulls, and cranberries. In a larger window from 1972, she again mixes religious and local imagery. For this piece, Leighton chose two Biblical stories involving the sea: Jesus calming the storm from the Gospel of Mark and Jesus calling two fishermen to be his disciples in the Gospel of Matthew. These windows display bold linework, dynamic compositions, and a sense of place.

At the top of the largest window at the Methodist Church, Leighton included the shell of a bay scallop. It points downward, and the ridges of the shell fan outward toward the two scenes from the gospels, like rays from heaven. It’s a clever detail, referencing both art history and the local landscape. It’s also emblematic of what Leighton did best: finding beauty and the sacred in the most humble of details.