When you step into Mike Sullivan’s winter studio in the grand living room of the house he’s renting in Provincetown’s East End, three things hit you right away.

The first is the hot breath of the space heater in the corner. Next is the midafternoon light pooling over the masks and headpieces that Sullivan sculpts from found objects like wasp nests and rhinestones.

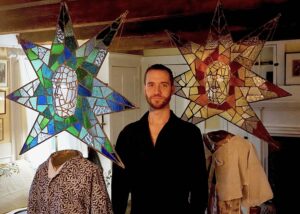

Finally, there are the two genderless mannequins in the center of the room, dressed in flowing garments and crowned with twin masks, stars of stained glass that shift in shades of red and orange, blue and green. The masks and mannequins seem as if they might launch into commentary, Greek chorus-style, and build the scene of a yet unspoken narrative. In short, you get the sense that a show is about to begin.

That show started in 2020 when Sullivan came to Provincetown for a monthlong artist residency at the former Stowaway guest house at 210 Bradford St., now the Summer of Sass house. Steve Azar, who owned the Stowaway and now owns the Gifford House, was struck by Sullivan’s application. In those early days of the pandemic, his use of the mask as a symbol felt prophetic and honest.

“His art has a way of capturing what we’re feeling,” says Azar.

Sullivan stuck around town, finding summer gigs comanaging the Cape Codder Guest House and singing at venues like the Gifford House and Tin Pan Alley. His creative output has expanded remarkably quickly, with the help of people in town who became friends and mentors. Gaston Lacombe displayed his work in the Lacombe Gallery. Christie Andresen, owner of Taqwa Glassworks Studio, taught him stained glass. Sullivan recently displayed some of his bejeweled masks at the Schoolhouse Gallery.

Now that the season is over, Sullivan is moving inward for the winter. Orbiting his studio, he moves with the full-body physical control of a dancer. It’s a slow-loping grace that reveals Sullivan as highly conscious of the space he takes up. To him, presence is a prism that can ground and expand the possibilities of the self as subject. This quality infuses his artwork.

“There’s got to be a sense of reality,” he says. “I have to keep it down to earth to some degree, while also being in the clouds, in the light, in the beauty and mystery of life and creating.”

Sullivan is not just a sculptor but also a photographer. He says his method is rooted in the time-sensitive urgency reflected by queer gathering and activity. Sometimes, that means bringing his camera on nights out and seeing what happens. Other times, he turns the camera back on himself.

He unwinds some portrait books he stitched together with thread and stretches them across the living room floor. One displays dozens of portraits of queer New York at night: drag queens and twinks and nonbinary angels playing in the darkness. He spent a few years in the city after graduating from Ithaca College, where he studied musical theater. Another book shows friends, strangers, and Sullivan himself on the dunes near Provincetown and in the marshlands of Connecticut, where he grew up, modeling the masks, headpieces, and crowns he creates.

Sullivan says collaboration with other artists and designers helps to expand his creative approach. They hold a mirror up to him in thinking about presentation, identity, and how he fits into the queer spaces that have been so influential for him.

The project on display in the center of the room, which features Sullivan’s foray into stained glass and garment design, was funded by the Provincetown Business Guild for the Carnival parade last August. It’s a collaboration with the Indian-British fashion designer Urvashi Lele, whom Sullivan met last year on a trip to southern India. The skirts and dresses produced by Lele’s collection Maison Audmi, a name that combines the Hindi words for woman and man, subvert traditional menswear. His friend and roommate Molly Tucker helped sew the garments based on Lele’s designs, which Sullivan then stamped by hand with floral patterns he carved onto linoleum blocks.

“Working with and learning from Urvashi helped inform my approach to deconstructing the binary,” Sullivan says. “Her designs accentuate a person while also stripping away societal expectations.”

This project also helped Sullivan frame and give words to what he is exploring in other projects. In working with natural materials, he realized he was evoking a universal connection to nature to build a bridge with those who might not understand queer expression.

“This is a way in which I feel secure and confident in relating to people both like myself and not,” he says.

He recently translated this mode of relating to a new medium. On his laptop, he queues a music video he recently produced with Tucker’s help. It’s a first edit, he says before hitting play. He shifts his weight, crossing and uncrossing his legs, as the dark screen slowly lightens. He rests his chin on his palm.

A scene appears: an empty beach during some liminal moment of orange light — it’s unclear whether sunrise or sunset. A voice — his voice — emanates from the speakers and tucks into the shelves and hollows of the living room. He’s singing a Celtic folk song, accompanied by friends on violin and piano.

Sullivan’s masks flash across the screen in scenes of Provincetown, New York, and Connecticut, synthesizing his creative journey and breathing life into the static portraits on the floor. Sullivan hopes to show the music video in town later this winter. In the meantime, he’ll be brainstorming what comes next.

“I’m not at all finite with what I do,” he says. “This is ever developing and quadrupling and growing and lessening. It’s moving.”