Autumn Group Show at Alden Gallery

The current autumn group show at Alden Gallery (423 Commercial St., Provincetown) features work by 16 artists represented by the gallery. Founder and curator Howard Karren says he assembled the show to give particular emphasis to artists “that were in some ways overlooked in the summer.”

The works of Portland, Maine-based artist Kevin Cyr and Fort Worth, Texas-based artist Linda Reedy feature prominently. Cyr’s precise paintings of trucks and cars — many of which depict actual vehicles he encounters around Brooklyn, N.Y. — make these very real machines look like toy trucks. This uncannily perfect style makes the dings, dents, and graffiti on the Swedish Fish truck in Herald all the more striking, both out of place and inseparable from the vehicle itself.

Linda Reedy’s work focuses on moody landscapes, including houses around Beach Point in Truro. Her paintings have an odd familiarity to them, especially Evening Fog, which depicts a dark, empty suburban street lit by streetlamps and the light pouring out of neighbors’ windows. The scene is eerie yet cozy, finding peace in the solitude of a quiet evening.

The gallery is open Saturdays and Sundays and by appointment, and the show is on view until Jan. 1. See aldengallery.com for information. —William von Herff

Evaul’s White Line Prints

William Evaul has been a fixture in the Outer Cape arts community since arriving in Provincetown in 1970 as a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center. In 1979 he began researching white line prints for an article he was writing for Print Review magazine. The printmaking technique, which a group of Provincetown artists invented in 1915, quickly captivated his imagination.

A year later, when he was asked to give a lecture about the prints at the Swain School of Art, he decided to try it himself. “How could I walk into a room full of artists to talk about a printmaking technique I had never tried?” says Evaul.

At the time, the art form had faded into obscurity. “This was right before it got rediscovered,” he says. He taught himself the technique by reverse engineering the process, and since then Evaul has largely dedicated himself to creating white line prints in the tradition of the Provincetown Printmakers. An exhibition of his work at the Wellfleet Adult Community Center’s Great Pond Gallery (715 Old King’s Highway) tells the story of his engagement with the form. The exhibition runs through December with an opening reception scheduled for Sunday, Dec. 10 from 5 to 7 p.m.

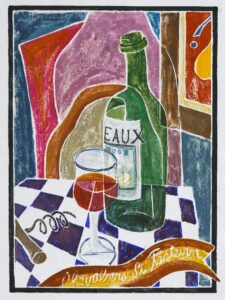

Titled “Whence They Came, Whither They Go,” the exhibition is historical, presenting the first white line prints Evaul created alongside more recent work. There are plenty of touchstones spanning this times, including Amis Des Vins, a still life that Evaul considers his thesis print — an image where he moves beyond the study of craft and toward something more personally expressive. Since then, he has been driven by the challenge to add something new to the form. “What didn’t they do?” he asks. “What can I give to the process?”

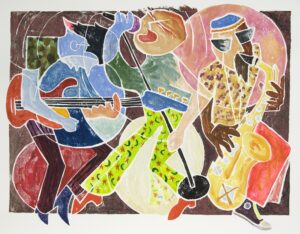

His innovations include creating white line prints with oil paint and printing on canvas. He also brings new imagery to the form. Although he doesn’t shy away from the traditional imagery of boats and Provincetown townscapes, he also incorporates more modern and urban subjects in his rollicking compositions, including rock musicians and the New York skyline.

The exhibition is a testament to an art form that keeps giving — and one that Evaul helped resurrect with devotion and inventiveness. —Abraham Storer

A Layered Look at the Provincetown Art Community

Collage is one of the most accessible art forms, requiring little more than a pair of scissors and some glue. The Cubists and Surrealists were early pioneers of the form, excited by both its possibilities for free association and the way it directly embodied the detritus of everyday life.

In a current exhibition at the Provincetown Commons (46 Bradford St.), cocurators Karen Cappotto and James Ryan reflect on the legacy and versatility of the genre in a collection of art that seems to include the entire Provincetown art community. The open, exploratory, anything-goes ethos of collage is reflected in the salon-style curation and an inclusivity that brings together established artists and beginners. “It’s a snapshot of who is working in town,” says Cappotto.

Some of the artists in the exhibition are already at home working in the format, like Deb Mell, who is represented by a bedazzled collage of mythical creatures circling around a mound. Kurt Reynolds, a sculptor who typically works with found material, has a framed piece, War Envelope/Dresden, which places historical ephemera in a handsome composition of burlap, aged paper, and netting.

Although there is plenty of loud work — including a garish bust of a mannequin covered in magazine clippings and rhinestones — some of the quieter pieces encourage close looking and reward the viewer with subtle surprises. Jay Critchley’s monochromatic collage spells out a phrase in small metallic squares that are camouflaged in the sand-covered surface of the page. Jen Bradley uses a similar earthy palette in her abstract composition of painted paper dominated by two enigmatic white shapes mirroring each other.

Some of the collages move in the direction of painting, like Fran O’Neil’s Harmonic Converge, which seamlessly integrates two cutout planets into a flat abstract arrangement. Other pieces move toward sculpture, like Mary Gallagher’s circular composition of delicate pink moths sitting on pieces of driftwood. And still other pieces integrate both sculpture and painting, including, most notably, Oscar Morel’s inventive townscape.

It’s a fun show that reflects the freedom and possibility of collage as imagined by the Provincetown art community. The exhibition is on view until Dec. 10. See provincetowncommons.org for information. —Abraham Storer

Kongero’s ‘Haunting’ Nordic Sounds

The music of Kongero, who will perform on Tuesday, Dec. 12 at Thacher Hall (266 Route 6A, Yarmouth Port) as part of the Payomet Road Show series, doesn’t fit neatly into the a cappella category, although they perform unaccompanied by musical instruments. Instead, the all-women group — consisting of Anna Wikénius, Sofia Hultqvist Kott, Lotta Andersson, and Emma Björling — sing what they call “Swedish folk’appella” in a repertoire that includes songs both with and without lyrics. Their voices range in pitch, timbre, and volume but are always perceptibly and inextricably blended.

On its website, Kongero’s sound is described as “haunting.” Listening to them perform, it’s easy to imagine their sound resonating long after they’ve stopped singing. The Nordic folk music they perform has been passed down through oral tradition and often involves ornamented melodies and dissonant harmonies.

The group has made five full-length albums. The newest, Live in Longueuil, was released in 2021 and includes a wide range of songs. Some pulse with energy, with consonants acting as percussion; some move slowly, lingering almost uncomfortably on dissonant harmonies — especially major and minor second intervals — until those dissonances begin to resolve themselves.

In addition to performing, the members of Kongero often conduct workshops and master classes. They describe how teaching and sharing their music is a rewarding part of their artistic expression: “To share is to gain something new.”

Tickets for the concert are $20 to $25 at tickets.payomet.org. —Dorothea Samaha

Applications for Dune Shack Residencies Now Open

A series of funded residencies — including ones for emerging artists of color and indigenous applicants — will give visual artists and writers an opportunity to live and work in the historic dune shacks of the Cape Cod National Seashore next year.

The residencies are organized by the Provincetown Community Compact, the nonprofit organization that manages two of the shacks. Established by artist Jay Critchley in 1993, the Compact is a community-building, philanthropic entity supporting the creative vitality of the Outer Cape community.

There are three visual artist residencies, including one for an emerging artist of color. It is named for the late David Bethuel Jamieson, a Black artist who spent time in Provincetown and died of AIDS in 1992. The recipient will get three funded weeks in the C-Scape dune shack and a $500 fellowship. Artist residents are selected by a jury.

The Compact will also underwrite two one-week residencies for writers, to be chosen by lottery. Two additional writer residencies are available through a collaboration with the Fine Arts Work Center.

In addition to the artist and writer residencies, the Compact will again underwrite a week’s residency next year for a Native American applicant in collaboration with the Native Land Conservancy. To move beyond “land acknowledgement” statements and offer tangible financial support for the use of unceded lands, Critchley says, the Compact will also continue its voluntary honor tax request for all residency applicants.

“An honor tax is a tangible way of honoring the sovereignty of the Wampanoag and other Native American nations,” says Critchley in a statement accompanying the announcement of the residencies. “It should not be thought of as a gift, but rather a step towards repair and healing.”

Contributions to the Native Land Conservancy are tax-deductible. Critchley states that $2,000 was raised for the NLC in the past year.

The two historic dune shacks that the Compact manages — the Fowler and C-Scape shacks — are among the 19 shacks in the Peaked Hill Bars National Historic District of the Seashore. The primitive, isolated shacks are without electricity or indoor plumbing and allow for uninterrupted solitude. The Compact maintains and administers the shacks under an agreement with the National Seashore.

The residencies will take place between April and November next year. Applications are due on Jan. 15, 2024. See thecompact.org/dune-shacks.html for information.