PROVINCETOWN — The light still blazes in artist Anne Packard’s blue eyes as she fixes her gaze on Long Point. She can see it through the wide windows in the second-floor studio above her home in Provincetown’s East End.

Neighbors have reported watching her shimmy down from her deck —willing herself to the water for a swim. At 90, she is a force. Her full voice carries over the harbor at midday: “Where’d you run off to, Cynthia?” Her daughter, Cynthia Packard, was puttering nearby a moment ago. The studio is full of paintings still being worked out, and oil paint finds its way to every surface — a little light pink Anne used for a sunset brightens the carvings of a blue dresser.

Packard works from a wheelchair now — three years ago she lost a leg to circulation problems. She says her arm doesn’t want to paint anymore. But nothing will keep her from the canvas. As she talks, she dips her right hand in mineral spirits and then into the oils, painting the dark horizon line of a dunescape with her hand.

“I paint nostalgia,” Packard says. Her canvases and boards are covered in the mystery of the sea; her skies are in motion. She is known for painting Long Point and the lone boat. “The lone boat, the lone boat, the lone boat,” her daughter chides. The two battle it out at times, Packard says, but Cynthia is her biggest champion.

“In repeating myself, I’m looking for more,” says Packard. She is not afraid to fill large canvases with rolling dunes and sweeping tides that cover the shore. Her deep palette casts shadows over half a forest, leaving only a strip of light on the water. When she can’t get what she needs out of her brush, she’ll push her palm on the canvas — rubbing and scraping the landscape with her hands.

Anne Locke grew up coming to Provincetown in the summers, selling fishing trips on the pier. She was born in Hyde Park, N.Y., but her family’s ties to the town reach back to the early 20th century when her grandfather, Max Bohm, lived and painted here. His painting of an early town meeting hangs behind the Provincetown Select Board in the Judge Welsh meeting room at town hall.

As a child, Packard painted and drew, but her family wanted her to go to secretarial school. She married and had five children in seven years. Toward the end of her marriage, she started painting on shingles out on Sandy Neck in Barnstable during the family’s vacations there. That’s when she noticed an ache inside her. “I knew the tide was going in and out here,” she says. “What the hell was I doing?”

Her husband ran off to Europe with a 19-year-old in 1973, and Packard says it was the best thing that ever happened to her. She kept his last name. Four years later she and her children moved from Princeton to Provincetown and rented the house she now owns for $1,800 a summer. “It was a total wreck, but we didn’t care,” she says.

She hung her paintings on the fence near her car and sold them for $15 to $25 — always worrying that a buyer would feel ripped off and come back at night to get her. But it put food on the table. After she’d sell a painting, she says, she’d cry, “We eat tonight, kids!”

Although she is primarily self-taught, in those early years Packard studied with Philip Malicoat. He was a great teacher, she says, but had a problem with her selling her paintings on the fence. Malicoat told her she was prostituting herself and that he wouldn’t continue working with her unless she took them down. She refused. He didn’t back down.

Soon enough, she did get gallery representation. “Steve Fitzgerald had a little gallery called Hell’s Kitchen,” she says. “He was an old-fashioned gallery person who took you on and helped you. He was difficult to get along with, but he was pure, he was honest, he loved art. He died of AIDS in the 1980s.”

Later, though, falling-outs followed when galleries would not give her the names of people who were buying her paintings. So, Packard set up her own gallery in the little house in front of where she lives now. In 1988, she bought the old Christian Science church, where she still shows. She carried the work of other artists, but over time she narrowed it down to family. Next to her works are paintings by daughters Cynthia and Leslie.

Thirty-five years later, Packard has put the gallery up for sale. The decision came after her last opening, this past Aug. 26.

“We had champagne and oysters and more than 200 people came,” she says, “all encouraging me to keep going.” And she will, she says. “I will still paint, but I am not pushing myself anymore.”

The gallery is listed for sale at $3.6 million.

Packard says she has plenty of drawings, monoprints, and paintings to show if the sale takes time. She always keeps her sketch pad with her, drawing everything and everybody she sees.

In her sprawling oil painting Crashing Waves, the viewer faces the storm head-on as the waters rush the rocks in the foreground, spraying the upper half of the canvas. The painting captures the very moment the storm reaches the shore — a moment Packard has seen herself as storms have pummeled her house, tossing seaweed on her windows.

Evening Mist showcases Packard’s feeling for mystery. In the foreground, we are standing in the shadows at low tide, the sharp edge of a building or wharf cutting the sky. We are left with the last light of day; the bright washed sky is now beyond the backlit town, casting deep green shadows in the sand. The monument fades in the distance as the town vanishes.

For 50 years, Packard has kept painting and collectors have kept buying. But for the most part she has separated herself from the art scene in Provincetown. She didn’t join the abstract expressionists whose movement had taken hold in the midcentury. Instead, she held fast to figurative painting and romanticism. Figures such as Hans Hofmann and Fritz Bultman kept their professional distance from her, she says, guessing it was because they were men and she was a single mother with no money. She didn’t join clubs. She had friends, but they weren’t in the art world.

Except Motherwell. He bought 21 of her paintings, Packard says, and gave her a place to live for two winters. He would come to her house in the evening and just talk, she says, never looking at her but at the floor, telling her about his family and himself. Sometimes, though, he spoke in abstractions that were incomprehensible to her. She asked her daughter to translate: “I said, ‘Listen outside the door, Cynthia, and tell me what he said afterwards.’ ”

Although he must have recognized the vitality and innocence in Packard’s paintings, when she asked him for a few lines about her work for a gallery show, he said he couldn’t write about her since he was an abstract expressionist, and no one would understand why he liked her work.

Packard’s romanticism put her on the other side of “a social line,” she says. “Motherwell had many soireés at his house, and I was never invited to one.” She was undaunted. “I somehow took advantage of the time and slipped through the cracks,” she says. “I kept going, but I never expected this success. I never thought I deserved it.”

Success did not protect her from her share of tragedy. Just before she moved to Provincetown, her 18-year-old son, Stephen, vanished with his girlfriend on the Lost Coast of northern California and was never found. She’s lost two grandchildren. In 2011, Leslie’s son Blake van Hoof-Packard was struck by a car as he walked his bicycle along Route 6, returning from a stay in a dune shack. A decade later, Leslie’s other son, Stephen Rome, a restaurateur who also worked in the gallery, died of a drug overdose. Through it all, Packard has stayed at the helm of her family, guiding them through sorrow.

More recently, her lobster diver son Michael Packard spent 40 seconds in the mouth of a whale and survived. She appears in the film about Mike’s adventure, In the Whale, which sold out its screening on Nov. 5 at the Cape Cinema in Dennis.

Anne Packard may not have attended every soireé in Provincetown. But she became a dynamic painter — some would argue a legendary painter. She’ll paint with her brushes, and she’ll paint with her fingers. She’ll paint on one leg. She paints while giving an interview.

“I’m doing,” she says. Even now, she says she is constantly feeling out what “works,” making adjustment after adjustment, until Cynthia declares, “Enough!” But Anne Packard is never quite finished. She will just keep painting, as she has all these years.

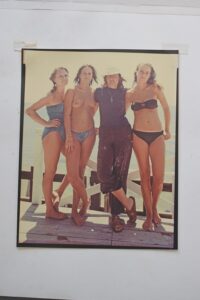

Surrounded by tubes of paint in her studio, Packard points to a photograph — not the one Joel Meyerowitz took of her and her daughters, but another less famous one. “That’s the story of my life,” she says. In the photo, she is giving a thumbs-up high above her head, under a sign that says, “Living well is the best revenge.”