Susan Dimock was a celebrated surgeon in the 19th century who died in a shipwreck in 1875 at age 28. In her short life she’d become a light of her era, having fled North Carolina with her family during the Civil War. Settling in Boston, Dimock apprenticed herself to doctors before being sent by benefactors to Zurich and Vienna to study medicine.

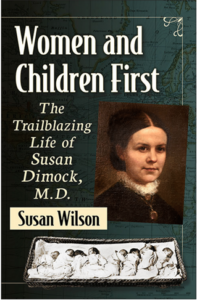

She helped train nurses and doctors and established one of the first American hospitals for women and children. The Dimock Community Health Center in Boston is named for her, though few people could tell you who Dimock was. That should change with the publication of Susan Wilson’s new biography, Women and Children First: The Trailblazing Life of Susan Dimock, M.D., published last month by McFarland & Company.

Wilson is a respected photographer (she was profiled in the Independent by Saskia Maxwell Keller in March 2021) and a writer for Equal Times and Sojourner. At the Boston Globe, she says, “I became the token woman, reviewing and photographing women musicians. Tina Turner, Judy Collins, Alison Krauss, Suzanne Vega. Before she was famous, Tracy Chapman waxed my car and painted my studio in exchange for photos. I traded portraits for guitar lessons with Patti Larkin.”

Wilson is also a historian and lecturer with her own history channel on YouTube. We recently sat down to talk about the origins of her latest book.

Sharon Basco: You spend half your time on the Outer Cape?

Susan Wilson: I try, yes. I brag that I’m in Wellfleet. I bought the house in 1990 with the intention of becoming a famous writer and being able to live here all the time. But most of my work is in Boston.

SB: You’re a musician, and you say you’ve always paid your bills by doing professional photography. But you’re trained as a historian. How did you first become aware of Susan Dimock?

SW: I fell in love with Susan Dimock back in 1995 and felt responsible to get her name out there. That’s because had she lived longer, like Louisa May Alcott or Julia Ward Howe or Isabella Stewart Gardner, people certainly would have known her.

I had a regular gig writing local history columns for the Globe. I’d helped revise the Freedom Trail to make it more inclusive and worked with the Black Heritage Trail and the Women’s Heritage Trail. I wrote a guidebook [Boston Sites & Insights: An Essential Guide to Historic Landmarks in and Around Boston, Beacon Press, 2004].

I would sometimes go down to the Boston Public Library and flip through the microfilm and look for interesting stories from the past. One day, I started reading about this horrible shipwreck — this was 1875 — and how upsetting it was because so many people were killed.

SB: A heavy fog caused the SS Schiller, a German transatlantic ocean liner, to hit ledges off the Cornish coast in southwest England, and 335 people died. Only 37 people survived.

SW: Dimock, this famous young doctor from Boston, died in that shipwreck. I put together a story about her death and why it was such a big deal and why she was important.

I was so struck by her story. The hospital where Dimock worked, where she was resident physician and chief surgeon, was the New England Hospital for Women and Children. It opened in 1862 and was only the second hospital in the United States run by women for women.

At that time, women who did professional things — like Mary Baker Eddy starting a religion [Christian Science], Julia Ward Howe significantly advocating for suffrage, Louise May Alcott writing a best-selling book, or Margaret Fuller being a famous journalist — all that was considered unacceptable. A lot of people didn’t think women should even be educated.

SB: So, had Dimock really been lost to history? Her name is connected to the health center in Boston.

SW: Right. I’m thinking, “Dimock — I’ve heard that name.” And then I realized it was the Dimock Community Health Center in Roxbury. And I began connecting the dots and found out she was buried at Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain.

With more digging I found the papers from the Dimock hospital. More papers about her were out at Smith College, and a few were at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe.

I put together a story for the Globe about her death. The people at the Dimock Center didn’t know she was buried at Forest Hills, only a few miles away. They also didn’t know that the founder of the hospital, Marie Zakrzewska, was also buried there. They didn’t know they owned a plot there.

You know how cemeteries like Mount Auburn in Cambridge have maps showing the graves of the famous people who are buried there? The people at Forest Hills Cemetery didn’t know she was famous.

SB: Didn’t you get involved with saving her tombstone?

SW: The Globe article was well received. Afterward I got a group of history people together, and we fundraised because her headstone was basically melting away, almost illegible. We brought in an expert from the Historic Burying Grounds Initiative, and she told us that in some cases you can carve deeper, but this was made of a kind of marble that was simply disintegrating. She recommended that we replicate it.

So, we did. We had the exact same thing carved in granite so it will last forever. Then we had a huge event rededicating the stone for her. This was in 1995. We also created a tour of famous 19th-century women at Forest Hills Cemetery.

I did some talks at the Dimock Center, but I moved on to other things. Forest Hills Cemetery hired me to write their guidebook because I was hanging out at the cemetery so much.

SB: You say you fell in love with Dimock in 1995. Is that when you started working on the book?

SW: No. It wasn’t until 2014. My friend Mary Smoyer, who I worked with on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail, asked me to give a lecture on Dimock to the Jamaica Plain Historical Society. I said, “Mary, that’s so 1995.” And she said, “Susan, you’re about to have knee surgery. You have nothing better to do for the next three weeks.”

It was a snowy night in March 2014. I was on crutches, on heavy-duty meds, and I gave the lecture to a standing-room-only crowd. People adored it. And they came up and said, “We would love to buy this book. Where can we buy it?”

And I said, “I’ve got to write it first.”

I applied for funding from the Women’s Studies Research Center at Brandeis, and I was accepted in 2016. That’s how this came about.

SB: What’s your fondest hope for the book?

SW: That at the very least it will be an inspiration for young girls, for women, for people in STEM, because Susan Dimock was in the sciences. I would be thrilled if high schools and colleges and medical schools picked it up, because unfortunately we’re still struggling to prove ourselves as women.