The Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival is no stranger to the strange, but this year is something else. At the 18th annual festival this week, Williams’s lifelong love of science fiction and fantasy takes center stage, as Richard Read wrote in last week’s festival preview.

Festival curator David Kaplan is quick to point out that the standard Williams canon includes the flat-out bizarre and totally cartoonish. Anyone who’s been to the festival in recent years has likely seen something a little out there, whether it’s a Cocaloony Key bird the size of a human or Cat on a Hot Tin Roof’s Brick played by, well, a brick. This year, that strangeness will be manifest rather than latent; the program eschews Williams’s classics in favor of his stories, one-acts, and other texts that demonstrate his lifelong love of the otherworldly.

Some theater companies might see an obstacle in this focus; others see opportunity. “It’s important to remember that science fiction has been dismissed as a literary form,” says Brenna Geffers, cofounder and principal director of the Die-Cast Ensemble of Philadelphia, “but it is so rich and so inviting for the imagination.” The company relishes filling unconventional spaces, in a literal and metaphorical sense, with thought-provoking theater.

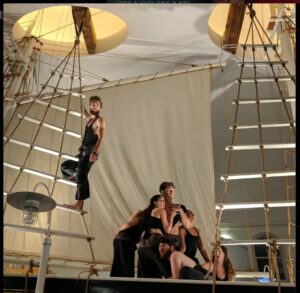

Geffers and Die-Cast have performed at four previous festivals, including a memorable Pericles aboard the Provincetown Public Library’s replica of the Rose Dorothea in 2017 and, most recently, Demolition Downtown in 2021, exploring a suburban family’s reaction to Armageddon. This year, Die-Cast is presenting The Sci-Fi Hotel Plays at the Harbor Hotel and Weird Anthology at the Crown & Anchor. Geffers notes that the former has been in incubation for many months while the latter will come together only when the entire cast, crew, and staff of the festival converge on Provincetown.

Kaplan and Geffers were both awed by Williams’s The Hotel Plays at the Gifford House in 2017, but they had to wait for the effects of Covid to diminish before presenting another version of the same conceit. The Sci-Fi Hotel Plays consists of The Strange Play, The Chalky White Substance, and Chronicle of a Demise — on the surface, plays that deal with time travel, nuclear war, and cult leaders. For Geffers, “they become a triptych of a world beginning to crumble, then in devastation, and then on the precipice of rebirth.”

Eight actors and a musician, along with Geffers, have been developing this production since last November. “Sometimes our pieces take a year and sometimes a couple days,” she says. But the company cultivates a long rehearsal process that allows them to experiment not only with time and space but also tone, theme, sound, and movement. Geffers says that Die-Cast’s ensemble work combines Suzuki training, contact improv, and the percussive methods of the Attis Theater of Athens, Greece.

Despite all the preparation, Geffers knows there is one actor the company will get to rehearse with only right before performances begin: the Harbor Hotel itself. “Hotels are infested with this sense of temporariness, which, for these three pieces on the precipice of change, will be helpful,” she says.

Then, there’s Weird Anthology — exactly what it claims to be. This work, a premiere of sorts, is a mélange of texts from the ’20s and ’30s pulled directly from Weird Tales magazine — stories of witchcraft, aliens, and monsters, letters to the editor, and even ads, as well as some text from Williams himself, whose first published work, “The Vengeance of Nitocris,” appeared in the magazine in 1928. There’s a lot to learn about Williams’s early imagination here, to be sure, but Geffers adds, “It’s also a wonderful celebration of a weird vintage pulp world.”

Kaplan and Geffers are proud to be including in Weird Anthology the poem “Taking Tennessee to the Coast” by Paul Ibell in an adaptation by Marios Mettis and his Cyprus-based company. In perhaps the most fantastical homage of the festival, the poem imagines a group of benevolent graverobbers who relocate Williams’s corpse from the family plot in St. Louis to where he actually said he wanted to be buried in his will: the Gulf of Mexico, as near as possible to the spot where the poet Hart Crane drowned himself in 1932.

The ocean as the great unknown is a theme that echoes across Williams’s work: Kaplan notes that Tom dreams of joining the merchant marine in The Glass Menagerie, while Mettis is most drawn to the fact that, in Streetcar, Blanche DuBois states her desire to die at sea and have her corpse thrown overboard. Mettis and his company have crafted a 13-minute multimedia piece to punctuate the performance and send off Williams’s weirdness with fitting aplomb.

Burial at sea somehow feels apt for Provincetown, too. And it’s hard not to wonder if Williams, with his potent connection to the town, might have found a taste of the fantastic here at the end of the Cape.

“There’s a sense of curiosity and grace, living on the edge,” Geffers observes, and Kaplan adds, “Provincetown is itself liminal — and time after time, Williams conflates going to sea with going to outer space.” That queer desire for elsewhere and the beyond helped catapult Williams and so many others to new frontiers of art and entertainment.

“His style goes way beyond Streetcar,” says Geffers. “There’s always more to find.”

The 2023 Tennessee Williams Theater Festival runs from Sept. 21 to 24. For a list of performances and to purchase tickets, see TWPtown.org.