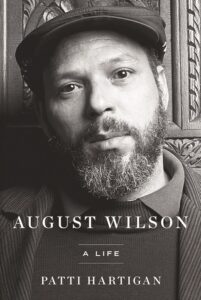

Eight years ago, the arts journalist and critic Patti Hartigan noticed something missing from the cultural landscape. August Wilson, a playwright whose works she cherished and had written about for decades, had died in 2005, but he’d never been the subject of a major biography.

Wilson started out as Frederick August Kittle Jr. Born in 1945, he was biracial, the son of North Carolina native Daisy Wilson and a German pastry chef who wasn’t around for much of the boy’s life.

Wilson grew up in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, which became the setting for most of his plays. He went to a Catholic school, then a vocational-technical high school, but quit in 10th grade. He loved the Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh, which became his virtual second home. As he devoured literature, he worked menial jobs, observing and absorbing the lives and language of the people he met along the way.

Memorizing street dialects and a vast cast of local characters, Wilson carried the Hill District with him when he moved to Minnesota. He wrote most of the 10 plays known as the “Pittsburgh Cycle” (a.k.a. his “Century Cycle”) there in the 1980s, depicting the experience of Black America in the 20th century. His plays won him success and fame: two Pulitzer Prizes (for Fences and The Piano Lesson) and many other awards, including two Tonys.

When I caught up with her by phone, Hartigan was on an unplanned break from her author tour for August Wilson: A Life. She’d contracted Covid on the road and was recovering in her part-time home in Charlottesville, Va. Following is an edited version of our conversation.

Sharon Basco: August Wilson may have been the most important — and consistently visible — playwright of the late 20th century, but no one had written his story. In 2016, you decided to do it. You say that, had it not been for the pandemic, you might still be taking notes and interviewing people.

Patti Hartigan: The silver lining was that I had to stop. If not for the pandemic, I would still be camped out in a library. I loved, loved, loved the research.

All the libraries closed. Nobody was flying. There were certainly not going to be any in-person interviews. People were sick, and people were scared. I had to retreat from research and just write the damn book.

There were moments of, oh my God, how do I organize this? I probably wrote the prologue 10 different times. When I nailed exactly where I wanted to start, that really helped.

SB: What are the most important things to know about August Wilson?

PH: He created one play for each decade of the 20th century — but it was really 400 years of history, written in a way that had never been done on the American stage before.

His first director, Lloyd Richards, told me that a white couple came up to Wilson after a performance and said, “Thank you for inviting us into a Black person’s home. We’ve never been in one before.”

He was giving voice to and celebrating a whole community of people in a poetic, funny, human way. Every single human emotion is in those plays. He also opened doors at the American theater. He was the anointed one, and everybody was doing his plays. He laid the groundwork for a generation of African-American playwrights.

SB: You came to Provincetown in November 2021.

PH: I was at a very difficult part of the book, and I just wanted to hunker down to finish what I had to finish. It seemed like Provincetown in the winter would have very few distractions. And I could see the sunset every day over the water.

Because of the pandemic, rental properties were scarce, but I found what looked like the absolutely perfect two-bedroom condo across from the Mussel Beach gym. I saw pictures: it was adorable, on the second floor, perfect for a writer to squirrel away in.

I packed up my little car and drove down from my home in Carlisle, and I was so excited. And I took it as a good sign that there was a parking spot. I knocked on the door and nobody answered. I called the contact number again and again. No answer.

I kept knocking until finally someone answered the door. It was a cleaning person who didn’t speak English. She connected me with her boss. The place I’d thought I rented was not there. The people I thought I’d rented from were probably in Russia.

And so I crossed the parking lot and went into the gym in tears. Two lovely men at the desk were extremely helpful. One was actually a dispatcher for the Wellfleet police, moonlighting at the desk. They gave me the name of a real estate agent and told me what to tell the police. I ended up getting the deposit back — I was surprised — and found a good place to rent.

I got to work — and it really was quiet.

SB: And you were able to hunker down and finish the book?

PH: It’s not like there were distractions. It was the pandemic, and everything was closed. I did yoga on Zoom. Even the church was closed. So there really was no outlet for human contact. It was like the people at the grocery store and the fish store were my best friends.

There aren’t direct connections between August Wilson and the Cape. But I could feel the spirit of Provincetown and the history and legacy of all those writers and artists.

SB: How did your own relationship with Wilson begin?

PH: In 1986, I saw Joe Turner’s Come and Gone at the Huntington Theater. I was freelancing for the Boston Globe, and I was the drama critic for the Tab newspapers. I was there that opening night. The room was full of people seeing and hearing this play for the first time.

It was electric, an extraordinary moment, sitting in a dark room before and after that play. When Wilson’s character Herald Loomis starts talking about the bones walking on the water, an image that represents the ancestors and the Middle Passage, it was just unbelievable.

And then, the next summer, I ended up at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center for the National Critics Institute. Wilson did not have a play that he was working on there, but he came every summer to the O’Neill to hang out with the playwrights and his friends.

Fences had won the Pulitzer and the Tony, it was still on Broadway. He talked to the critics, and afterwards I sat under a tree with August for hours, and he just regaled me with his stories. At the time I thought, “Oh, I just bring out the best in people. He’s telling me stories!” I later found out that he told the same stories to everybody. He was so good at it.

SB: Was there a high point, the best day of writing the book?

PH: Yes, but it didn’t have to do with words on paper. The best moment was when Renee Wilson, August’s first cousin, and I went down to Spear, N.C. We climbed the mountain where his great-grandmother lived, where his grandmother was born, and where his mother was born.

We had a local guy with us who had played on those trails when he was a kid, and he knew exactly where the homestead was.

It was October, it was raining, and we didn’t have hiking boots. We had sneakers on. And it was posted, so we had to climb over a fence, and we didn’t care. We found the homestead. August Wilson said he did not research his plays — he wrote from the blood’s memory. And you could just feel the blood’s memory coursing through that mountain and that homestead.

SB: As a journalist and critic, you’ve conducted many interviews. When you’re the one being questioned, do you say to yourself, “Hmm, they should have asked me this”? Are there obvious things people are missing?

PH: Of course. And regardless of who is doing the interview, I end up asking questions. I love talking to people.

I will tell you the one question I get that Wilson would have told you to skip. The question is: “Why do you think white people like his plays?” And my answer is: “For the same reason they like Shakespeare’s plays. They’re good plays. Period.”

SB: When you were in the zone writing, did you ever feel like you were channeling Wilson?

PH: The times that I felt his presence were times when I felt sad. It was really hard to write the last scene, at his funeral. I cried when I got home from my studio, and I looked at my family, and I just said, “I killed him today.”

And I remembered that when he was starting out, he had written this play, and he had to kill off a character, and he said he cried because he had never done it before.

I thought of him saying that when I had to do that in his biography. I wouldn’t say I felt a presence, but I truly could hear his voice sometimes, because I was quoting him so much.

I knew him, and I knew his voice.

August Wilson: A Life was published by Simon & Schuster in August. Patti Hartigan’s schedule of upcoming appearances is at pattihartgan.com.