On a mid-August night, amateur and published poets, locals and tourists, pour into the Somerset House Inn in downtown Provincetown and take seats on an array of couches and deep armchairs. The open back door lets in a breeze from the bay, and the low rumble of the crowds on Commercial Street mingles with the murmur of introductions, book recommendations, and laughter.

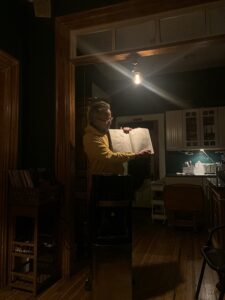

The room goes silent as the evening’s organizer and MC, Pat Kearns, steps to the front. His podium is a water cooler, and a bare lightbulb hangs just above his head. He looks out at the audience, smiles, and says, “Welcome to the 15th People’s Poetry Parlor!” before quickly adding, “Let’s begin the night with a poem.” He opens his notebook and reads “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin” by Pushcart Prize-winner Terrance Hayes. The words buzz in the air, there is a pause, then applause. The parlor has begun.

The People’s Poetry Parlor was started by Kearns, who has lived in Provincetown for five years, in the winter of 2021. His title at the Somerset House is creative director and keeper of the People’s Parlor. He says he was inspired to start the sessions because he loved attending readings at the Fine Arts Work Center but felt a need for a space where both established and unpublished writers could read their new work without judgment.

Since it began, the parlor has welcomed a wide range of readers and emphasizes growth rather than gatekeeping he says. “Poetry can be a really spiritual and grounding experience,” says Kearns, adding that making space for community poetry is particularly important in a “transient town” like Provincetown.

“People feel like the parlor is a home for them,” he says, “even if they’re passing through. The community extends out and through the parlor.”

Kearns has been writing poetry for the past 15 years. When he first moved to New York City in his early 20s, he says, he “didn’t know how to be an artist and live in the city,” but going to readings and writing poetry was a way to hold onto his sense of himself.

“I used to write poems on the walls of my New York apartments,” he says, adding, “I never got the security deposit back.”

As the evening at the Somerset House begins, Kearns checks his list of readers. He says that the parlor is “not an open mic,” but there is no formal vetting process for getting onto his list. Just having a quick conversation with him before the reading is enough to reserve a slot behind the water cooler.

Richard Carey, who works at East End Books in Provincetown, reads three poems that he describes as “action poems, things happening in the moment, happening right outside my body.” The last poem is in contrapuntal form, in which two separate poems are interwoven to create a single poem that can be read multiple ways. It is titled “One Night,” “To the Next,” and “One Night to the Next.” Carey says that it’s “important to have spaces to share our stories, especially in a time when they’re being questioned and taken off the shelves. It’s important not just to write them down but to speak them.”

The next reader is an eight-year-old visitor from Kansas City named Sarit Chaisanguanthum. He carries his iPad, whose screen brightness is turned up all the way. It illuminates his face as he walks to the water cooler — to loud applause.

“I am writing a book,” says Sarit, “so my mom says I should read from it.” He begins reading a series of couplets that bring cheers from the crowd, a particular favorite being “Mouse in my house/ Fart in my heart.” After the reading, Savit says that he’s on a path to his first collection and that he has been writing poetry “since yesterday.”

Sarit’s mother, Devika Maulik, an obstetrician-gynecologist in Kansas City, reads as well. Her poems are about being a doctor and her childhood practice of praying to Hindu deities in hopes of preventing nuclear war.

After Maulik, Mark Adams, who is artist-in-residence at the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown, reads stories and shows watercolor drawings of his time working at a refugee camp in Greece. A few others read before Kearns calls up Aaron Lecklider, a professor of history at UMass Boston and part-time resident of Provincetown. He walks up to the cooler.

“The last time I read something new at the parlor,” he says, “I had a two-month-long anxiety attack.” If he is nervous now, however, it doesn’t show. He reads a poem about memories of childhood with his brother and his sexuality, and referring to the wealth and exclusivity he sees in Provincetown.

Lecklider says that, for him, poetry is a “form of creative expression outside of professional writing” and that the parlor is important because of its “democratizing impulse,” being outside the confines of a formal institution.

“People are hungry for opportunities to connect in ways that aren’t governed by consumption, by buying things, by drinking,” he says. “It’s about creating a certain kind of vulnerability outside the structures of exclusivity and money.” He relates it to the influx of the hyperwealthy in Provincetown and says that money “creates gatekeeping” but that “creative expression doesn’t have to exist in that kind of economy.”

As the night winds down, Kearns reads a comic original poem about gay real estate agents, the audience cheers, and he thanks everyone for being there. He says that the parlor happens every month and is open to the public, but you have to ask him exactly when the next one will be. Luckily, Kearns isn’t too hard to spot in town. The parlor’s spontaneity is part of what makes it special.

If you’re taking an evening stroll past the Somerset House, keep your ears open for poetry.

Editor’s note: Because of a reporting and fact-checking error, an earlier version of this article, published in print on Sept. 7, misspelled the names of Poetry Parlor readers Sarit Chaisanguanthum and Devika Maulik.