The Glittering Art of Bob Mackie

Cher, Tina, Liza, Diana, Beyoncé: Bob Mackie has dressed them all. Any time you think of one of those single-named superstars, you’re probably also picturing his work. Mackie’s designs were so essential to their public images that they quite possibly might never have become legends without him.

Would Cher have landed the cover of Time if she hadn’t been photographed wearing that sheer sheath of carefully placed beads? Could Diana Ross still have thrilled her audiences in a pantsuit that didn’t sparkle? Would Marilyn Monroe have scandalized the nation if she’d sung “Happy Birthday” to JFK in a dress that was more demure? (Yes, Mackie designed that one, too.)

You’ll have an opportunity to consider these questions and others when East End Books (389 Commercial St., Provincetown) celebrates the release of a new book, The Art of Bob Mackie, on Aug. 29 at 5 p.m. Mackie will appear in conversation with producer and director (and long-time friend) Dan Guerrero to shed some light on what it was like to have a hand in shaping the public images and destinies of so many famous women.

The book marks the first time that Mackie, 84, has granted full access to his archives and personal memories. It’s a lavish celebration of the achievements of this Tony Award and nine-time Emmy Award winner, three-time Oscar nominee, and recipient of the Geoffrey Beene Lifetime Achievement Award from the Council of Fashion Designers of America.

Tickets for the event, which will also be livestreamed on Facebook, are $5. See eastendbooksptown.com for information. —James Judd

Withers’s Dindin Makes Its Big-Screen Debut

In the fall of 2020, amid the isolation, fear, and frustration of the coronavirus pandemic, the four cofounders of the Harbor Stage Company — Brenda Withers, Robert Kropf, Stacy Fischer, and Jonathan Fielding — whose Wellfleet theater had been shut down for the summer, mounted an online reading of Withers’s new play, Dindin.

A poisonous cocktail of a comedy about two artists and their two wealthy hosts pawing and preying on one another at an evening meal, the Dindin reading was a success on the shared small screens. In a bold step, the still stageless quartet decided to turn the play into a feature film. To direct, they enlisted Brendan Patrick Hughes, who had brought them together onstage in 2008. Hughes, in turn, enlisted his wife, Emily Topper, as cinematographer. They raised $100,000 and filmed it in the spring of 2021, weeks before it would cap the company’s hastily relaunched live theater season in August and garner rave reviews.

In a world shaken and stirred by Covid, it may not be so odd that a movie adaptation of a play might be shot before the stage production is mounted and then debut at a film festival a year later. And that is precisely what the Harbor Stage is announcing: the world premiere of the movie Dindin at the Middlebury New Filmmakers Festival in Middlebury, Vt. on Friday, Aug. 25 at 7:15 p.m.

The Harbor Stage will close for a day so Withers, Kropf, Fischer, and Fielding can be there for a Q&A with Hughes and the festival’s artistic director, Jay Craven, at Twilight Hall on the campus of Middlebury College. See dindinthemovie.com for more information about the film and its festival screening. —Howard Karren

Mia Cross’s Weird and Colorful Worlds

Mia Cross, whose work is on view in a new exhibition at AMZehnder Gallery (25 Bank St., Wellfleet), remembers carrying a notebook everywhere she went when she was growing up. “I would draw stained-glass patterns,” she says. And not just patterns — she drew “lots of everything.”

AMZehnder Gallery in Wellfleet. (Photo by Patrick Dolan)

While she took advanced placement art classes in high school, she thought she’d major in marketing or TV production in college. But things turned out differently. “I applied to a couple of art programs on a whim,” she says. “I landed in a program at Boston University.” In 2014, she graduated with a double major in painting and sculpture.

Cross says that an especially influential color theory class opened her eyes in a new way. “A color can change just by what its neighbor is,” she says. “It’s magic.

“I’m always trying to dance with the colors,” says Cross. While she’s drawn to primary colors — red, yellow, and blue — she strikes a careful balance between bold and subdued. When considering the intricacies of color relationships, she follows her instincts: she says she feels a “tingle” in her brain when the colors are right.

The figures in Cross’s art are often people she knows. “My goal is to make the people become characters in a story,” she says. “It’s like their imagination is surrounding them. I create these rooms — this person exists in their own little weird world.”

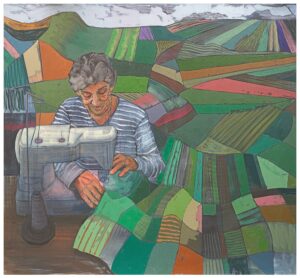

In Looking for the Perfect Starflower for You, a young girl sits on the ground. Her red socks are vibrant against the grass, and she holds a sprig of delicate white flowers in her hand. A blue bird in the corner casts a shadow on her leg. In The Land Stitcher, an old woman uses her sewing machine to stitch a colorful patchwork quilt. The quilt, stretching out behind and around her, becomes a patchworked landscape, familiar and warm: her own weird world.

The show is on view until Aug. 29. See amzehnder.com for information. —Dorothea Samaha

Terry Abrahamson Celebrates the Blues

Grammy Award-winning songwriter Terry Abrahamson will perform an interactive show, “In the Belly of the Blues,” at Wellfleet Public Library (55 West Main St.) on Monday, Aug. 28 at 7 p.m. The program, which is based on Abrahamson’s memoir of the same title, includes stories, photos, and musical performances detailing his years of working closely with Chicago blues legends.

Growing up in Chicago, Abrahamson was exposed to blues music just by walking down the street. “People were sitting on stoops listening to the radio,” he says. “I heard words like ‘choo-choo-chaboogie’ and ‘hoochie-coochie’ and ‘wang-dang-doodle.’ ” Although he wasn’t paying much attention at the time, he says “it kind of sunk in.” His love for the genre emerged when he was a teenager after he heard Howlin’ Wolf and his band playing in a bar. At the University of Illinois, Abrahamson began booking blues bands even though the school wouldn’t pay for them. As a young man, Abrahamson wrote three songs with legendary blues singer Muddy Waters. One of them, “Bus Driver,” won Abrahamson a Grammy Award.

Abrahamson’s passion for and dedication to the blues tradition remains strong. He says the genre is especially important now. “This music has been political from the start,” he says. “It remains of tremendous value in our society.” Through music, “you can tell people that you’re worth paying attention to, that you have something to say, that your life matters,” he says.

Abrahamson thinks of himself as a writer and entertainer. “I use that entertainment to get people to live a kinder, gentler, more community-focused, more history-focused life,” he says, adding that blues music, which he calls “America’s first, most resonant, and most relevant art form,” is a way of finding identity: “You can give yourself an identity that no one thought you should have.

“We’re living in a pretty cruel world,” Abrahamson adds. “The blues are a celebration of our history. They’re a celebration of creativity, ingenuity, and perseverance. They show the importance of community, the importance of understanding the past, and being able to draw on those lessons to make a better world.”

The program is free. See wellfleetlibrary.org for information. —Eve Samaha

Remembering a Year With the Wellfleet Police

When writer Alec Wilkinson arrived in Wellfleet in 1975 to become a policeman, he was fresh out of college, plagued with postgraduate ennui, and looking for real life to “forget about taking LSD and playing rock-and-roll.” He was young and impressionable and didn’t have a day of policing experience. But his year-long stint as a patrolman left enough of a mark on him that, soon after, he wrote his debut book, Midnights: A Year With the Wellfleet Police, recounting his evenings on duty and the characters he encountered.

Wilkinson will return to Wellfleet almost 50 years later to talk about the book, which was recently reissued, on Wednesday, Aug. 30 at 7 p.m. at the Wellfleet Public Library (55 East Main St.).

A lot has changed in Wellfleet since Midnights was first published in 1982. The Wellfleet police now have double the number of staff and a lot more than the two police cruisers the department had when Wilkinson served. But the small-town idiosyncrasies of the people that Wilkinson calls “colorful, hard-bitten New England types” still ring true.

In Midnights, Wilkinson describes his rounds on Main Street, traffic stops with belligerent drunk drivers, and slipping away from duty to read books late at night in the Lighthouse Restaurant, to which the Wellfleet police had a key. In one anecdote, Wilkinson describes fumbling an arrest of a drunk teenager on the lawn of Town Hall, only to later discover that the boy was in fact the son of the select board chair at the time.

Despite his occasional ineptitude, Wilkinson says he found kinship among his fellow officers. “Even as incompetent as I was, I was working within a shared context of brotherly feeling that protected me from harm,” he says.

Wilkinson describes the experience as “immensely broadening.” In fact, he believes it is an important reason why, soon after returning to New York City, he landed a job as a writer at the New Yorker. “I went back into the world of all these people who felt the same way and did the same things, and I had a radically different experience from theirs,” he says. “I did what writers should do, which is to have experience.”

Since Wilkinson wrote Midnights, he has published 10 more books, including his most recent memoir, Divine Language, in which he chronicles two years of trying to relearn the calculus he struggled with in high school. He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Lyndhurst Prize, and a Robert F. Kennedy Book Award.

The talk is free. See wellfleetlibrary.org for information. —Sam Pollak