Mira Schor’s life as an artist wasn’t predetermined, though her parents, Ilya and Resia Schor, were both artists.

“You have to make the decision for yourself,” says Schor. As an art history major at NYU in the late 1960s, she made her choice: “I realized during lectures that I was on the wrong side of the slide projector,” she says.

But Schor’s annual summer migration to Provincetown feels more predestined: In the 1950s, her family — father, mother, and two daughters — rented an apartment in the East End. After her father died in 1961, the three women continued their annual sojourn. In 1969, when Schor was 19, her mother bought a small house on Anthony Street.

The house was filled with “creative woman power,” says Schor. Downstairs, her mother would work on her small sculptures and sculptural jewelry. Upstairs, Schor would paint. Schor’s sister, Naomi, a scholar of French literature and critical theory, might be “in another little room, working on a book.”

In the winters, the family lived in New York City, as Schor still does. Her parents, who were Polish Jews, had moved to France and then fled to New York to escape the Holocaust.

“I thought about the Greek myth of Persephone and her mother, Demeter,” says Schor. “Persephone ends up having to spend part of the year in Hell and the other part with her mother on Earth.”

Resia died in 2006, but Mira has come back every summer to the same house, “a very productive place” where, she says, she’s created about half of her life’s work.

Schor’s current show at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, “The Summer Studio,” attempts to organize a selection of her artwork into a single story.

The show’s earliest piece is from 1974, the latest from 2022. The works have a wide range. Low Tide, from 1980, deals in indistinct color — the browns, grays, and blues of low light on the sea. Suggestions of human figures, rectangular and fragmented, appear weightless on the landscape. In Create Resist, from 2017, everything feels heavy: the oily black background, the red and yellow, the figure with a skull-shaped head and wide round eyes who’s thinking deeply at her desk.

The pieces are similar in their “relationship of intimacy to the work,” says Schor. “I want people to get up close.” Schor herself likes to hold and touch the artwork she’s interested in. The pieces in “The Summer Studio” are also similar in that they were all created in Provincetown, and “couldn’t have been done anywhere else,” with one exception: she painted the largest canvas, Hello, Goodnight, in New York in 2022. In it, the white silhouette of a woman waves at the viewer, standing against a background of shadowy blue. In the corner, what looks like a full Moon sends droplets of dark water, or maybe projected moonlight, toward and past the woman.

“It’s based on a photo I took of my shadow with my iPhone,” says Schor. She took the picture on the beach in Provincetown.

Curator Breon Dunigan sees another commonality among the pieces in the show: “Whatever topic Mira is engaging in, there’s a beauty with which she lays down a mark,” she says. “There’s a lot out there about Mira Schor the feminist and Mira Schor the writer and teacher. I wanted to celebrate Mira Schor the painter.”

A few of the pieces in “The Summer Studio” have never before left her house in Provincetown, says Schor. One is Self-Portrait, completed in 2019. The painting is glossy, thick with oil paint. It took two years to dry. Schor’s profile, outlined in black, seems to glow like a hot ember; the orange paint is like a “molten material,” she says. In the painting, she stares into impenetrable blackness.

Another is Left Over From a Previous War, from 1990, which shows an ear connected to a vaguely gun-shaped penis, which sprouts an American flag that dissolves back into the ear.

“I went to a lecture by the art historian Leo Steinberg,” says Schor, recalling an incident from the 1980s. “He went off on a little tangent about how, in the Middle Ages, monks would sit around trying to figure out how the Virgin Mary got impregnated. And they decided that the word of God, through the angel Gabriel’s fingers, penetrated her ear.”

In Left Over From a Previous War, the ear represents the “female receptive organ,” says Schor. “And then you have this dick-head — or gun. I was interested in the way patriarchy just reinfects itself. It’s this perpetual system. So here” — Schor points to the dissolving flag — “it’s like defeat. But then it’s pulling right back into the ear, and out.” The penis shape takes its lifeblood from the ear and becomes erect enough to support the staff of the flag in a proud and self-destructive cycle.

Feminism defines Schor in some ways. “I grew up in a time — and I don’t think our time is really all that different, despite everything — when I was a very good student,” she says, “and I knew that that was not valued.” As she grew older, she read more: Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, and Virginia Woolf. “Feminist ideas were kind of seeping in,” she says. “And I happened to be the age where I was forming myself when second-wave feminism took off.”

She went to the California Institute of the Arts for graduate school. There, in 1972, as part of the Feminist Art Program, Schor participated in “Womanhouse,” an art installation and performance space in which women renovated an abandoned Victorian house in Hollywood, redefining the idea of “homemaking,” and filled it with art.

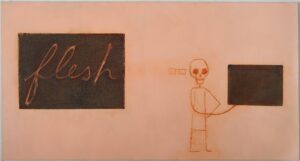

“The Summer Studio” features several pieces that use language as images, including Suddenly, Trace, Writing, and Flesh. Schor says that “women are filled with language,” and these works are a physical manifestation of that idea. “Women are filled with hopes, with philosophy, and we’re not given credit for it,” she says.

Her art has always seemed to explore the intersection of gender, art, language, and power. As a child, she says, she drew “powerful women”: goddesses and queens. They were often also writers; in the drawings, they had pens in their hands, and there was “text all over the floor.”

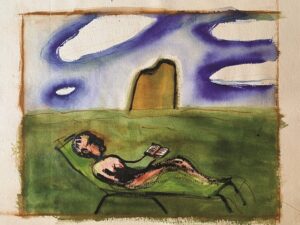

But not all of Schor’s art is obviously feminist or has anything to do with her politics. For the show, Dunigan has chosen pieces like Red Nipple, from 1993, but also Lawn Chair Floating in the Bay, from 2022, in which Schor reads a book while floating in Cape Cod Bay.

“The Summer Studio” doesn’t try to sum up Schor’s political and social activism. Instead, it reflects her love for Provincetown’s landscape, through which her “soul gets replenished,” in Dunigan’s words. That landscape has inspired and enabled every phase of Schor’s art.

In The Bay at 7:30 P.M., from 1982, there is a shape. “It’s based on skate egg cases you can find on the beach,” says Schor. The shape is almost human: a rectangular main body with two sets of slender arms, one on each end. In the late ’80s, when Schor started to make her more gender-oriented works, “that same shape became a bullet or a sperm.”

Schor remembers works that aren’t in “The Summer Studio,” done in the mid ’70s: unframed rice-paper figures roughly the height of a person and shaped like dresses. She says one male viewer told her: “You know, by putting something so fragile into a public space, you’re doing something very assertive and aggressive.”

“The Summer Studio” doesn’t include such fragile things as rice paper, but it does feel somehow delicate. Schor describes a “dreamtime relationship” with Provincetown’s water bodies, a seasonal drift and her yearly migration back to her mother’s East End house as a necessary cycle for her artmaking.

From Commercial Street, looking through PAAM’s front window, viewers can see the glowing white body of the woman in a dress in Hello, Goodnight as she waves them inside, perhaps assertively, for a closer look.

Creative Woman Power

The event: Mira Schor’s ‘The Summer Studio’

The time: Through Sept. 17; Wednesday-Monday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Fridays till 8 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: General admission: $15