Classical concerts rarely feature pieces composed by women. Three women composers who draw inspiration from the Outer Cape discuss how they found (and are still finding) their ways in an artistic field that has historically been dominated by men.

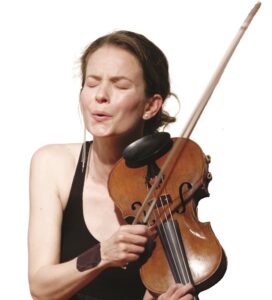

Roseminna Watson

Violinist and composer Roseminna Watson, who lives in Providence, R.I., is the originator of the Music in the Studio concert series in Truro, now in its second year. She started on the violin when she was three. Her mother, composer and violinist Clyde Watson, left Roseminna alone with the instrument for an entire year. Then, for the next seven years, Watson’s mother was her teacher. The daughter attributes her unique ease and movement-based playing style partly to that independent introduction.

Watson majored in visual art at Yale, then got a master’s in violin performance at the State Universtity of New York at Stony Brook and an artist’s diploma in chamber music from the San Francisco Conservatory. She was first violinist in the Aiana String Quartet in residence at the University of Texas.

“I’d had this seed of an idea for a long time,” Watson says, “about composing a piece for myself. Maybe incorporating movement or a visual aspect.” Caught up in the whirlwind of professional musicianship, Watson simply didn’t have time.

But in 2013, the quartet broke up. “All of a sudden, boom,” Watson says. “Everything disappeared.” She decided to take a step back from performing. “I felt that I had gotten too far away from the root of why I play music.”

Her husband, musician Pablo Escalante, whom she met in Austin in 2012, plays the sitar, didgeridoo, and Native American flute. They began to sing folk songs together. He got Watson a USB microphone that she could plug into her computer. She started to experiment with recording her solo improvisations on voice and violin.

For Watson, making music has always been intensely physical. In improvising, she says, she felt a link between her body and the outside world. “Everything was in a loop, and synchronized, flowing in and out.” What she describes is sometimes termed a state of “flow” — where time seems to stop and players feel connected to an invisible energy. Tuned in to this energy, Watson played the violin and sang, often at the same time.

Listening to hours of her recorded improvisations, Watson would cut out “tiny clips,” she says, and paste them onto a new track on her computer. She doesn’t use traditional musical notation — she either doesn’t write down anything at all or writes out “reminders” in her own sparse and wandering notation style.

The first piece she composed, in 2014, is called Limbic Hymnal, for violin and voice.

“It alternates between very intense, high drama violin,” she says, “and placid, hymn-like segments.”

In 2019, Watson composed Lullabies for Icarus, also for violin and voice. “I think it’s eerie,” she says. “The myth is about the lack of ability to stay between the Sun and the water. Mankind has never been good at that.”

She will perform both Limbic Hymnal and Lullabies for Icarus on Friday, July 28 in the next offering in her concert series, which takes place in artist Cammie Watson’s studio.

Watson says her music draws from several genres. “There’s an element of Western classical,” she says. “But I also draw on meditation music or hymns. There’s a sacred quality, especially in moments with the voice.”

She doesn’t think of herself as a composer. “I’m not at all trained as one,” she says. “I think of it as making stuff up.”

When she improvises, “there’s a sensation of inevitability,” she says. “I’m not controlling it, and there’s nothing I can do to stop it. All of sudden, in my body, I know what comes next. I can see where my fingers are going to go before they go there.”

Lullabies and Hymns

The event: Music in the Studio: Violin & Violin, Roseminna Watson and Lillit Hartunian

The time: Friday, July 28, 7:30 p.m.

The place: Cammie Watson Artist Studio, 6 Swale Way, Truro

The cost: Suggested donation: $22; reserve at roseminnawatson.com

Amelia LeClair

Beginning her undergraduate music studies at UMass Boston in 1972, Amelia LeClair was the only girl in every composition class she took. She had been “entranced” by musical notation since starting piano lessons at age nine. But growing up, she says, she had “zero female role models” for composing. Several men, including her father, told her that girls shouldn’t study composition.

“I thought, wow, there just aren’t any women composers,” LeClair says. “I’d never heard of one. And why would I want to do this thing that girls clearly can’t do? So, I gave it up.”

She graduated in 1975 with a degree in music theory and composition but didn’t try to make it as a composer. Living in Boston, she tuned pianos for 25 years. “I was trying to be somewhere on the periphery of music,” she says.

In her 50s, LeClair discovered that women composers actually did exist. She took some courses with Laurie Monahan, head of the voice department at the Longy School of Music. Monahan introduced LeClair to the world of women composers from medieval times to the present.

Inspired, LeClair went back to school and got her master’s degree in conducting from the New England Conservatory. In 2004, she started Capella Clausura, dedicated to performing “the unheard, ignored, and erased music by women composers from the ninth century to the present day,” she says. The group performs both a capella and with instruments ranging from Baroque harp to modern violins.

LeClair also returned to composing.

“My greatest influence, musically, is early music,” she says. “Music from around the 14th and 15th centuries and into the Renaissance.” She composes mainly for voice but adds instrumental parts if the piece needs it.

Early music is “wonky and unusual,” she says. “It tickles my funny bone. But it also tickles my beauty bone.”

Her music is inspired by texts that she finds or writes. In 2020, LeClair composed Anthem to Truro, a choral piece celebrating the birdsongs of the place where she has spent summers for 35 years.

LeClair composes with words first. Before writing the music, she wrote a four-stanza lyric poem. The second stanza reads: “When Truro wakens to the spring,/ The broom and heather glowing,/ The quail calls toot sweet,/ The gulls callay, the mourning/ Dove laments her day;/ The towhee drinks her tea.”

“I wrote the words to try to get that musical sense of the birdsong,” she says.

The piece hasn’t been performed or recorded yet. But in an mp3 file provided to the Independent, computerized voices sing a simplified version of the work. The four-part vocal piece is characteristic of early music chants: dissonances melt into harmonies, which quickly shift back into dissonances. It sounds like birdsongs overlapping in the woods.

LeClair is also influenced by the works of female troubadours — lyric poets of the 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries — which she found in feminist scholar Meg Bogin’s book The Women Troubadours. While their poetry has endured, the music that went with their words had been lost.

“I commissioned four different composers, as well as myself, to take their poetry and give it music again,” LeClair says. She ended up with six short pieces in the styles of jazz, classical, quasi-early music, Bengali music, and hip-hop. Capella Clausura performed them in 2021.

She says, “We brought these women who had been languishing in the pages of books for a really long time back to life.”

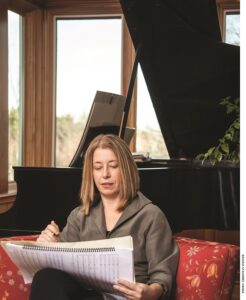

Elena Ruehr

Composer Elena Ruehr splits her time between Brookline and Wellfleet. But she grew up on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. “It looks a lot like the Cape, but hillier,” she says. “And less developed. It’s very, very wild.” She grew up surrounded by music. Her father was a math professor and her mother a teacher of the deaf; both were amateur musicians.

“My dad was a big-band piano player,” she says. “My mom was a folk singer for little kids’ shows.” Ruehr’s mother was her first piano teacher, starting her when she was three.

“She is the reason I’m a composer,” Ruehr says. “She saw that I was playing my own little pieces. She taught me how to write them down.”

With her two brothers, Ruehr played a game called “Rainstorm” at the piano.

“We’d say, ‘Here’s the story,’ ” she says. “It’s a rainstorm, and you’re thunder, and I’m lightning, and you’re rain. We’d sit at the piano bench together and bang around. We didn’t know what we were doing. But it was improvisational fun.”

When she was 11, Ruehr began studying piano more seriously. She discovered that her family’s piano tuner, Melvin Kangas, had a degree in composition from the University of Michigan.

“He was a chicken farmer, a teacher, a musician, and a piano tuner,” she says. “He became my teacher.”

From him, she learned how to compose in all kinds of different styles. She was the pianist in a “rinky-dink rock band.” After high school, she says, “I got an offer to go on tour with a professional rock band. Or I could go to college and study classical music. I didn’t really have any question in my mind of what I was going to do.”

She majored in composition at the University of Michigan, then got her master’s at Juilliard. But trying to get her work performed was “really hard,” Ruehr says.

“Conductors didn’t take me seriously,” she says. “You’re this young kid. And you’re a woman. They’d say, ‘Oh, who’s that girl?’ ”

She moved to Boston in 1990, where she got two big breaks. The first, in 1991, was a job teaching in the music department at MIT. Then, a couple of years later, a commission from the Metamorphosen Chamber Ensemble, conducted by Scott Yoo. They asked Ruehr to compose a piece for their inaugural concert.

“They didn’t pay me anything,” Ruehr says. “And they gave me only two months to go from the idea to the finished product. I was composing like crazy.”

She composed Shimmer, now one of her most popular works. The piece, performed by the Metamorphosen strings, is both melancholy and uplifting. It has the grandiose sound of traditional classical music and the unpredictable, shy feeling of something more modern.

“For Shimmer, there was a genre or cultural idea called minimalism, which was popular in the ’80s and ’90s,” Ruehr says. “But I’m really interested in the idea of being a conservator” — in the sense of preserving the tradition of classical music.

“My music is related to other classical music,” she says. “I’m not very worried about being avant-garde.”

Ruehr was a composer-in-residence with the Boston Modern Orchestra Project for five years. From there, her connections in Boston allowed her to become sought after for composing commissions. She writes about 10 pieces a year, from operas to string quartets.

Her 9th string quartet will be performed by the ES Quartet in Middlebury, VT, on July 28th. That piece, along with Ruehr’s 10th quartet (titled “Long Pond” after Wellfleet’s Long Pond) and her 11th quartet (titled “Long Night”) will be recorded by the ES quartet in a CD to be released in a year.

She starts with a pencil and staff paper, then moves to the computer, which she uses to listen to her work-in-progress. When a piece is finished, she says she just knows: “There’s a sense that a story has been told.”