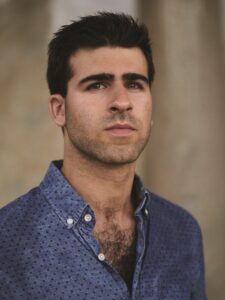

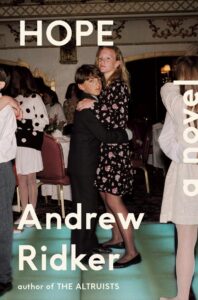

A Novel of a Family’s Tailspin

Much of Andrew Ridker’s second novel, Hope, is set in Brookline, where the author grew up. The satiric novel follows the year-long implosion of the seemingly perfect Greenspan family — Harvard-educated doctor, refugee-resettling mother, and their brilliant children — and although Ridker says that the Greenspan family mirrors his own, “The things that the characters do in the novel are far more outrageous and dramatic than anything we’ve ever done.”

Ridker spent childhood summers at his grandmother’s cottage in Wellfleet, and the Outer Cape makes several appearances in the book. He will be reading a Cape-centered excerpt from Hope at the Wellfleet Public Library (55 West Main St.) on Thursday, July 27 at 7 p.m. The talk will also include a conversation on craft with his sister and fellow writer, Elena Ridker.

Ridker’s first novel, The Altruists, was a New York Times Editors’ Choice. But he says that, despite that success, approaching the blank page anew was daunting. “No matter how good or accomplished a previous book might be, it’s a very humbling thing to start again,” he says. “It’s like learning how to write all over again.”

While Hope is set only 10 years ago, Ridker says he had to do a tremendous amount of research to inhabit that time. “I approached the writing of the novel as a work of historical fiction, even though it was set in the recent past,” he says. “The Obama years when it’s set and the Trump-Covid years that I was in while writing are so drastically different.”

Ridker says he hopes readers will reflect on how much America has shifted since 2013. He says, “I hope people laugh when they read it, I hope people cringe when they read it, and I also hope that people think a little bit about how we got from the optimistic days of Obama to our embattled present.”

Ridker says the novel also attempts to explore the ways Jewish history and culture influence an otherwise secular modern American family. “How does Jewishness manifest in a time when many of us are non-observant?” he asks.

Ridker’s reading is free. See wellfleetlibrary.org for information. —Oliver Egger

BETTY Makes a Splash

“Talking, laughing, loving, breathing, fighting, f*cking, crying, drinking, riding, winning, losing, cheating, kissing, thinking, dreaming.” If that string of words means anything to you, then you already know BETTY. While the band’s theme song for the series The L Word and subsequent appearances on the show may have introduced them to legions of lesbians with Showtime accounts, the legend of BETTY spans decades.

Since forming 37 years ago at the 9:30 Club in Washington, D.C., the indie rock-pop trio have amassed a devoted queer and feminist following — and plenty of straights, too. Renowned for their energetic sound and political activism, they are a perfect fit for Provincetown, where they’ll play a four-show run at the Post Office Café and Cabaret (303 Commercial St.) during Girl Splash this week.

The band is composed of guitarist Elizabeth Ziff, her sister Amy Ziff on cello (which becomes a uniquely rollicking instrument in her hands), and Alyson Palmer on bass and guitar. The three share vocals, often ricocheting off each other in harmony.

BETTY has had summer gigs in Provincetown since the late ’80s. “It’s a holiday culture of entertainment, and that’s rare,” says Elizabeth. “People accepting each other, loving each other, and just getting joy from each other.”

The Post Office Café and Cabaret is “intimate, it’s fun, it’s inclusive,”she says. Sometimes too intimate: a few years ago, Elizabeth accidentally kicked Amy’s cello across the stage during a sound check, and an Outer Cape odyssey to find someone to repair the instrument ensued.

The shows will feature a mix of the band’s deep back catalogue and an upcoming new album — their 11th — recorded with Grammy-winning producer Jason Carmer, an old friend. Elizabeth says the pop-skewing record is “the best thing we’ve ever done.”

As usual for BETTY, this summer has been packed with Pride performances, including one with Christina Aguilera at Hudson Yards in New York City. “Especially now, politically, it’s more important than ever to play for Pride and have a voice in the mainstream world as well,” Elizabeth says.

Amid the whirlwind of everyday life — Palmer and Amy each have two kids — an extended visit to Provincetown is also a chance for the women of BETTY to spend time together. “It gives us an opportunity to be more chill with each other and just have fun like the old days,” says Elizabeth.

General admission tickets are $35. See postofficecafe.net for information. —Amelia Roth-Dishy

A Summer of Robert Henry

This is the summer of Robert Henry, whose 90th birthday is being celebrated with exhibits at Wellfleet Preservation Hall, the Wellfleet Public Library, his own BHA Gallery, and the Berta Walker Gallery.

Henry has an abiding respect for the Outer Cape’s artist community. “There are still artists doing vital, interesting art” here, says Henry, himself a Wellfleet year-rounder. His legacy includes teaching at the Fine Arts Work Center, the Cape Cod Museum of Art, and Brooklyn College. In addition to Berta Walker Gallery, he regularly exhibits at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum and the Cape Cod Museum of Art.

Henry describes the show at Walker (208 Bradford St., Provincetown) — which includes mixed-media works on paper, pencil and charcoal drawings, watercolors, gouaches, and oils spanning seven decades — as a mini-retrospective. “The earliest are from 1953, the year I started studying with Hans Hofmann, until this year, with works from every decade in between,” he says. “Most have never been exhibited.” The show is on view until Aug. 5.

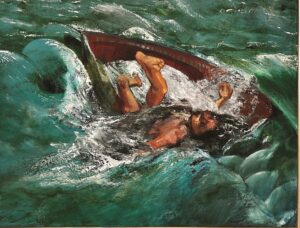

At Wellfleet Preservation Hall (335 Main St.), Tabitha Vevers and Dan Ranalli curated “Three Henrys,” on view through July 25. Three galleries include selections from Henry’s “Ship of State” series — paintings of people in boats or “awash in rough seas,” says Vevers, that were made during the 1990s — along with paintings from his “Interiors” and “Coat Rack” series. The works are on loan from Berta Walker Gallery.

Henry himself has curated “Well Red” in the meeting room of the Wellfleet Public Library (55 West Main St.), on view through August. “It’s a relatively small room,” Henry says. “So, I thought I’d put up a bunch of red paintings that people couldn’t ignore.”

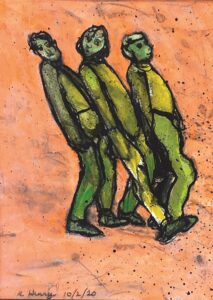

Henry opened his BHA Gallery (42 Commercial St., Wellfleet) five years ago after the death of artist Selina Trieff, his wife and soulmate for almost 60 years. His inventive “Pairs” series, capturing a range of emotions through gesture and line, is currently on view there.

In addition to exhibiting in these spaces, Henry has a presence on Facebook, where he posts his own work and selections from Trieff’s haunting “Master Drawings” series, as well as “For Artists and Art Lovers,” a series of reflections on art and artists informed by his decades of teaching that are intended for eventual publication. During this summer of Robert Henry, it’s time for the master to take a bow. —Susan Rand Brown

Chris Firger at Alden Gallery

While still highly regarded and influential in their home country, the early 20th-century Canadian landscape artists known as the Group of Seven remain little known outside of Canada. For Haverhill-born artist Chris Firger, however, they have been a longstanding source of inspiration.

“I went to college in Canada, at McGill University in Montreal, and my wife is Canadian,” says Firger in a statement accompanying his new show at Alden Gallery (423 Commercial St., Provincetown), opening this week. “The Group of Seven brought this grandiose, bold approach to the landscape — taking what you love about what you’re seeing and pushing it.”

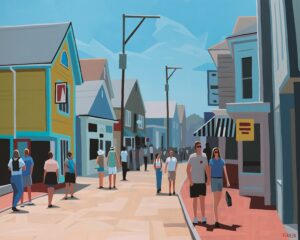

Inspired by these antecedents, Firger’s views of Provincetown are characterized by simple shapes and blocks of color that recall both picture postcard views and the schematic, almost abstracted shapes of mid-century paint-by-numbers compositions. But his paintings are far from simple or rote. Instead, his abstraction of land- and townscape elements and figurative characters is an intentional strategy.

“I utilize clean lines and intentional edits to simplify scenes and emphasize certain elements that I find interesting, unexpected, or important,” Firger says. “My work invites the viewer to create their own narrative about a given place or moment in time.”

There’s a sense of timelessness and serenity in Firger’s views of Provincetown, something especially apparent in two views of Commercial Street in the show. The strolling figures in In No Rush seem suspended in time; the essential summertime chaos of the block between Standish and Ryder streets known to locals as “T-shirt Alley” becomes a tranquil plane of color, shapes, and forms.

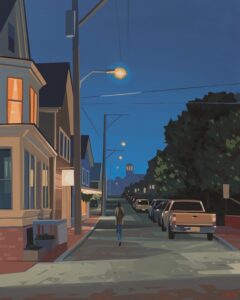

Similarly, Midnight on Commercial captures its location — the stretch of the street in front of Town Hall looking west — in a moment of nocturnal repose, as a solitary figure moves between rows of solidly rendered buildings and parked cars: a contemporary scene that nonetheless looks much as it must have over half a century ago.

The show at Alden marks Firger’s first exhibition at the gallery, which he joined last year after previously showing his work in Eastham and at a Provincetown pop-up space. There will be an opening reception for the artist during the Friday gallery stroll on July 21 at 7 p.m., and the show is on view until Aug. 3. See aldengallery.com for information. —John D’Addario

Monsters and Goblins at the Schoolhouse

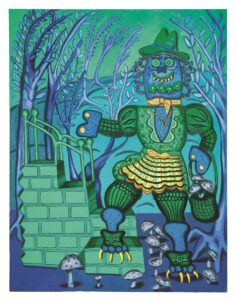

The subjects of the paintings by Hannah Barrett in a show opening at the Schoolhouse Gallery in Provincetown on Friday, July 21 are described by the artist as “monsters, or devils and goblins.” Barrett, director of the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College, has long explored shifting social constructs in their work.

In a painting from 2001 called Ancheny, a male-headed figure, afloat in joyful dance, has wide cloud-like hips and patterned bloomers, the body tapering off into a pair of strappy heels. Two decades later, Barrett’s style has shifted away from realism toward folk art, but iterations of the same narrative explorations abound. “I wanted these new paintings to be more future looking,” says Barrett, “almost a science fiction — like, what comes after binary?”

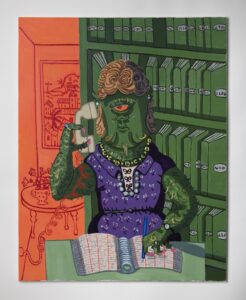

In the paintings at the Schoolhouse, one thing that surely remains is the clothes. Fanciful, throwback, vintage, and pattern-forward: Barrett’s monsters boast tortoiseshell glasses, front ruffles, frilled blouses, three-quarter ties, and impossibly adorable hair combs. A cyclops with a pile of curls and a goatee sits hard at work in One Ring-a-Ding, perfectly fitted into a cinched floral dress, and the regal seated figure in The Dark House sports a high-fashion bib with strawberry appliqué.

The stylized world of these paintings is influenced by literature. “As a teenager, I always hung onto passages that described interiors,” says Barrett. “Interiors couldn’t be sexist. Furniture and decor were neutralizing sanctuaries. They couldn’t make me feel lousy about myself.”

Now, the artist cites Muriel Spark, Iris Murdoch, and E.F. Benson as literary lodestars whose books explore morality, sentience, and social class. These concerns are also at work in Barrett’s recent paintings, particularly six pieces from the series “Word Processor,” with the monster as writer, drafting imagined text on computers and in notebooks or researching sources with a magnifying glass.

“In graduate school, my teachers always said, ‘Stop tickling!’ and ‘No little brushes!’ ” says Barrett. “They were like, ‘Get out the big brush and step back.’ But I like to be close to the canvas. I like a jewel-like surface.”

In Barrett’s works, the world is grotesque, delightful, and demanding, with the occasional consolations of etiquette and ornament. Life is hard, say the monsters. Get dressed and be serious. Have some fun.

A reception for Barrett and the other artists in the show, Mark Adams, Damien Hoar de Galvan, and Tess Michalik, is 6 to 9 p.m. on July 21. The show continues through Aug. 9. —Kirsten Andersen

Leslie Jonas Looks at the Big Picture

Leslie Jonas works across environmental realms. “It’s a blue and green picture,” she says. “The environmental picture needs to involve land and water.” As part of Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill’s John P. Bunker lecture series, Jonas will present a talk titled “Climate Change, Rewilding, Cultural Respect, and Environmental Self-Determination” at the Highland House Museum (6 Highland Light Road, North Truro) on Wednesday, July 26 at 6 p.m.

An Eel clan member of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, Jonas helped found the Native Land Conservancy in 2012 and currently serves as its treasurer. The conservancy’s mission extends beyond land and water preservation, says Jonas; it aims “to open access for indigenous people to practice their life ways, our life ways, on these lands, specifically in our homelands.”

Jonas teaches courses at UMass Boston and MIT that highlight the value of traditional ecological knowledge; works as a grant manager at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution; and serves on the Conservation Law Foundation Advisory Board for Massachusetts. “I think it’s my life’s calling,” she says.

Jonas aims to shed light on the vital role of indigenous perspectives in land and water conservation, which she describes as a knowledge system that “rounds out the information” and “provides a much more thorough examination.” The talk is free. See trurohistoricalsociety.org for information. —Georgia Hall

Exploring the Art of Process

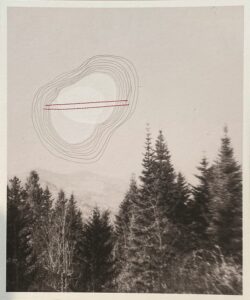

In a new show at Off Center Gallery (75 Commercial St., Wellfleet), artists Susie Nielsen and Connie Saems explore how complex processes and combinations of materials can be used to express the subconscious and “represent that which is not visible.”

The multimedia pieces in Nielsen’s “Holding Pattern” series begin with photographs taken with a 35mm film camera, which are printed on etching paper. Nielsen then incorporates biomorphic, kidney-shaped elements into the composition — similar to the ones she uses in her paintings — to create a sort of dialogue between the abstracted shapes and the more literal quality of the photographic images.

“These shapes sit out there in space, separate and together, floating, awkward,” says Nielsen. “The photographic images create the initial conversation for these shapes to engage with.” Stitched lines connect and occasionally separate the elements in the composition, creating a wordless and open-ended narrative. Nielsen describes the series as an ode to artist and illustrator Yoshitomo Nara: “The details of his subjects are minimal, and there is so much emotion without telling a story,” she says.

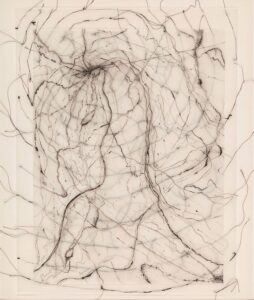

Drawing is also central to Saems’s process. Instead of combining drawn elements with photographic images, however, Saems uses a different variety of materials — including Mylar, thread, ink, and crushed paper — to build her pieces, which practically vibrate with a complex intensity.

“It’s all about a journey,” says Saems. “The path each line takes, I follow.”

The show opens on Saturday, July 22 and runs until Aug. 9, with a reception for the artists on Saturday, July 29. See offmaingallery.com for information. —John D’Addario